SCALING UP INSTITUTIONAL

INVESTMENT FOR PLACE-BASED IMPACT

White Paper

MAY

SCALING UP INSTITUTIONAL INVESTMENT FOR PLACE-BASED IMPACT – THE WHITE PAPER 2021

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

4

INTRODUCTION

8

1.1 Place-based approach to impact investing 9

1.2 Why the Local Government Pension Scheme? 9

1.3 This report 10

A PLACEBASED FRAMEWORK FOR INVESTORS

12

2.1 A conceptual model: the architecture of PBII 12

2.2 The stakeholder ecosystem 15

2.3 The five traits of place-based impact investing 17

2.4 The financial case for investing in the ‘five pillars’ 18

A BASELINE ANALYSIS OF INVESTMENT ACTIVITY BY LGPS FUNDS

22

3.1 The size distribution of LGPS funds 22

3.2 Intentionality and action in LGPS funds 24

3.3 Summary of findings 29

STAKEHOLDER PERSPECTIVES AND CURRENT PRACTICE

30

4.1 Barriers and solutions to scaling up PBII 30

4.2 Investment strategies 34

4.3 Investment fund models 37

4.4 Capacity, skills and competence – build, buy or borrow 42

4.5 The role of pension pools 46

IMPACT MEASUREMENT, MANAGEMENT AND REPORTING FRAMEWORK

48

5.1 Why impact measurement and management matters 48

5.2 Stakeholder perspectives on impact measurement 49

5.3 Approach to developing a PBII impact reporting framework 50

5.4 The PBII impact reporting framework 51

5.5 Next steps 57

MOVING FORWARDS

58

6.1 A national approach to PBII and levelling up 58

6.2 Recommended actions 60

6.3 Final reflection 65

ANNEX

66

Annex 1: List of individuals consulted 66

Annex 2: List of identified funds with LGPS investment 68

Annex 3: Example theories of change 74

CONTENTS

ABOUT THE PROJECT

The Good Economy, Impact Investing Institute and Pensions for Purpose have joined forces to

produce a white paper on place-based impact investing (PBII) that can mobilise institutional capital

to help build back better and level up the UK. Based on extensive consultations with market actors

and stakeholders, this white paper offers a clear set of directions, models and practical guidance

for investors to engage in PBII and report their impact across sectors and geographies. The Local

Government Pension Scheme (LGPS), the empirical focus of this project, could itself become a

pioneer of PBII in the UK, showing the way forward for the multi-trillion pound pensions industry.

This research project has been supported by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport,

the City of London Corporation and Big Society Capital. Our approach to the project has been

collaborative and consultative throughout, with LGPS funds, local authorities, fund managers and

other stakeholders contributing advice, guidance and practical support throughout the project work.

ABOUT THE PARTNERS

THE GOOD ECONOMY

The Good Economy (TGE) is a leading social advisory firm dedicated to enhancing the contribution

of finance and business to inclusive and sustainable development. Formed in 2015, TGE has rapidly

established itself as a trusted advisor working with public, private and social sector clients. TGE

provides impact strategy, measurement and management services and also runs collaborative

projects bringing together market participants to build shared thinking and new approaches to

mobilising capital for positive impact. TGE currently provides impact advisory services for over

£3.4 billion assets under administration.

IMPACT INVESTING INSTITUTE

The Impact Investing Institute is an independent, non-profit organisation which aims to accelerate

the growth and improve the effectiveness of the impact investing market. It does this by raising

awareness of, addressing barriers to, and increasing confidence in investing with impact.

PENSIONS FOR PURPOSE

Pensions for Purpose exists as a bridge between asset managers, pension funds and their

professional advisors, to encourage the flow of capital towards impact investment. Its aim is to

empower pension funds to seek positive impact opportunities and mitigate negative impact risks.

It does this by sharing thought leadership and running events and workshops on ESG, sustainable

and impact investment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the UK Department of Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, City of London

Corporation and Big Society Capital for their funding and support for this research. We would also

like to thank all the individuals and organisations who have supported this project by participating

in interviews, roundtables and providing case studies and data. A special thanks to Edward Jones

and Nicole Pihan for sharing the LGPS holdings data that they accessed through Freedom

of Information requests.

TGE CO-AUTHORS AND PROJECT TEAM

Sarah Forster, CEO and Co-Founder

Mark Hepworth, Co-Founder and Director of Research and Policy

Paul Stanworth, Principal Associate, TGE and CIO of 777 Asset Management

Sam Waples, Head of Data Analytics

Andy Smith, Head of Impact Services, Housing and Real Estate

Toby Black, Research Assistant

SCALING UP INSTITUTIONAL INVESTMENT FOR PLACE-BASED IMPACT – THE WHITE PAPER 2021

We define place-based impact investment as:

Investments made with the intention to yield

appropriate risk-adjusted financial returns as well

as positive local impact, with a focus on addressing

the needs of specific places to enhance local

economic resilience, prosperity and sustainable

development.

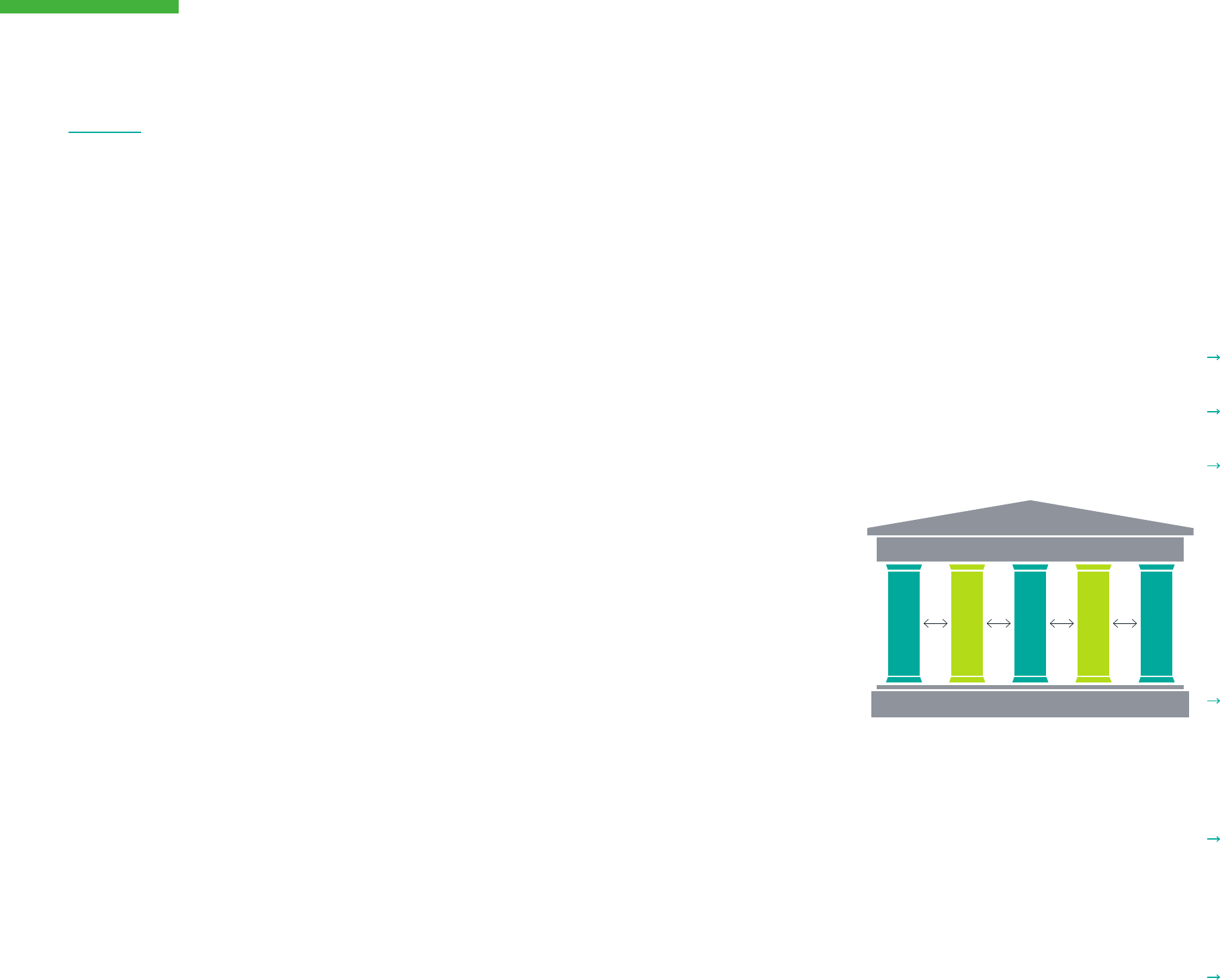

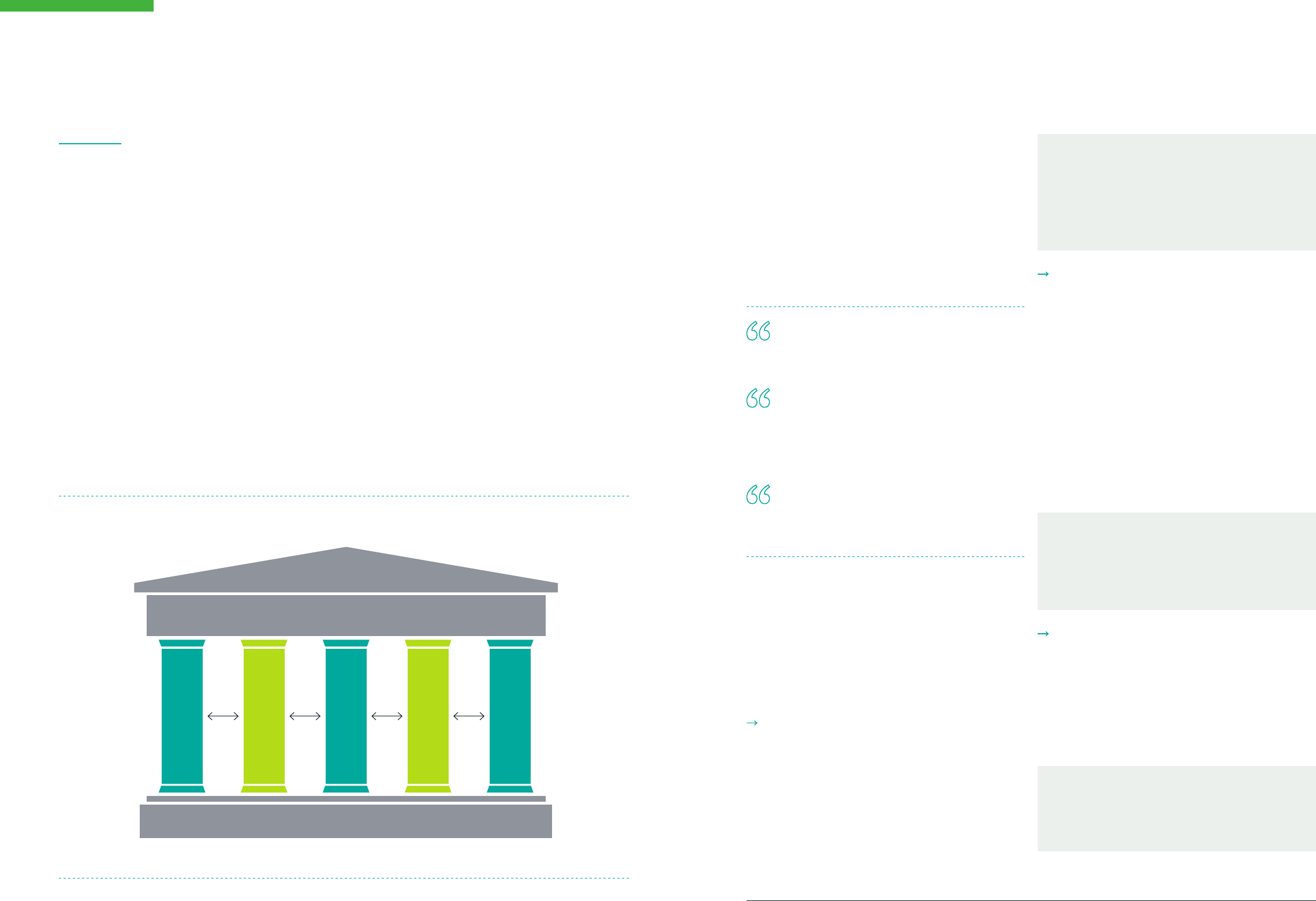

We present an original conceptual model of PBII that brings

together places and investors around five ‘pillars’, underpinned

by a solid social and financial rationale for investing (see

Section 2). The five pillars are dual structures. On the one hand,

they represent policy objectives and priority areas in local and

regional development strategies. On the other hand, the pillars

are real economy sectors and investment opportunity areas that

fall within institutional investment strategies and asset classes.

Central to PBII is creating an alignment of interest and action

among all stakeholders in shared impact creation for the benefit

of local people and places. Stakeholder consultation and

engagement is indeed fundamental to PBII. This type of investing

is about ‘boots on the ground rather than eyes on screens’.

The white paper also defines five traits that define

and distinguish PBII as an investment approach:

1 Impact intentionality

2 Definition of place

3 Stakeholder engagement

4 Impact measurement, management and reporting

5 Collaboration.

THE FINANCIAL CASE FOR PBII

For institutional investment to flow to PBII, it needs to meet

the commercial investment requirements of LGPS funds and

other institutional investors. We carried out original analysis of

market data which demonstrates that investments within the

sectors that are key to PBII - affordable housing, SME finance,

clean energy, infrastructure and regeneration – can deliver

risk-adjusted financial returns in line with institutional investor

requirements. Specifically:

Investments in these key sectors provide stable, high,

long-term returns and low volatility versus other mainstream

asset classes.

Investments in most of these sectors are generally in real

assets, such as housing and infrastructure, so can also

provide income streams.

These assets are generally illiquid which often command

higher returns, hence, are attractive from a portfolio

diversification and financial return perspective.

The universe of assets is, however, comparatively small and

often in the private markets, suggesting a need for manager

selection and a deeper understanding of the risks by interested

institutional investors.

THE OPPORTUNITY FOR LGPS FUNDS

Currently the scale of PBII is very limited. Our baseline analysis

of investment activity by LGPS funds in sectors that are key for

PBII found that:

Few pension funds demonstrate intentionality to invest

with a local place-based lens. We were only able to identify

six LGPS funds out of a representative sample of 50 that

have a stated intention to make place-based investments:

Cambridgeshire, Clwyd, Greater Manchester, Strathclyde,

Tyne and Wear and West Midlands. Of these, only Greater

Manchester has an approved allocation to invest up to 5%

of its capital locally.

There is a very low level of investing into key PBII sectors.

Only 2.4% of the total value of LGPS funds holdings are in

these key sectors, of which only 1% of total assets (£3.2 billion)

is clearly identifiable as directly invested in these sectors

within the UK. Infrastructure dominates in terms of the scale

of investment. SME finance provides the most opportunities

for direct local and regional investment through specialist

fund managers.

Key sector allocations are generally relatively small size,

averaging £10 million and busting the myth that pension

funds can only make large allocations in the £50 million

to £100 million range.

A PLACE-BASED APPROACH TO IMPACT INVESTING

The UK is a country of entrenched place-based inequalities which have persisted for

generations and are more extreme in the UK than most OECD countries. The Covid-19

pandemic and Brexit have combined to move these place-based inequalities to centre

stage in public debate – alongside a search for effective and sustainable ways of tackling

them. The need for more public investment is undeniable and the political will appears to

be in place. There is now a golden opportunity for responsible, patient private capital to

step in, match public investment and deliver positive environmental and social impact in

places and communities across the country.

Currently only a small fraction of UK pension money is invested

directly in the UK in ways that could drive more inclusive

and sustainable development, in sectors like affordable

housing, small and medium-enterprise (SME) finance, clean

energy, infrastructure and regeneration. This white paper

offers a place-based approach to scaling up institutional

capital, including pension fund investment, into opportunities

that enhance local economic resilience and contribute to

sustainable development, creating tangible benefits

for people, communities and businesses across the UK.

If we manage to accomplish this, the UK will be creating

bridges between London and the rest of the country, and

bridges between financial capital and the real economy.

Place-based approaches to tackling deep-seated social and

spatial inequalities are now the norm internationally and they

are relatively advanced in the UK. The current UK Government’s

levelling up policies are consistent with a place-based

approach. With the costs to the nation of levelling up expected

to exceed £1 trillion over the next 10 years, it is clear public

investment will need to be matched by private investment. This

is the rationale for our study, which explores how a place-based

approach, already favoured by public and social investors, can

be extended to institutional investors.

To establish an empirical basis for understanding place-based

investing, we chose to focus on the Local Government Pension

Scheme (LGPS). These pension funds are locally managed by

98 sub-regional administering authorities and have assets with

a combined market value of £326 billion as of March 2020 (see

footnote 6). The LGPS has a place-based administrative and

membership geography.

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) integration and

alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are

becoming increasingly important to investment strategies, and

there is a legacy and current interest in local investing. If all

LGPS funds were to allocate 5% to local investing, this would

unlock £16 billion for local investing, more than matching

public investment in the £4.8bn Levelling Up Fund and

associated government initiatives.

The levelling up agenda goes hand-in-hand with the climate

change agenda where pension funds already have a strong

focus, including how to build net zero portfolios. Delivering

these two goals together would support a ‘just transition’

to a net zero economy that supports green job creation and

simultaneously delivers environmental, economic and social

benefits across the UK.

We should emphasise, however, that we see place-based

impact investment (PBII) as a new paradigm and lens for

investors more generally. We envision PBII as a confluence

of capital from commercial, social and public investors that

results in equitable distribution of investment across all

regions of the UK for the benefit of local places and people.

This confluence of capital flows, with institutional investors

playing a key role, must happen if we are to make the levelling

up aspiration a reality. As such, we hope this report acts as a

template for change, and will be read and acted upon by all

institutional investors and financial institutions.

The project has been led by The Good Economy working in

partnership with the Impact Investing Institute and Pensions

for Purpose. The research project has been supported by the

Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, City of London

Corporation, and Big Society Capital.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

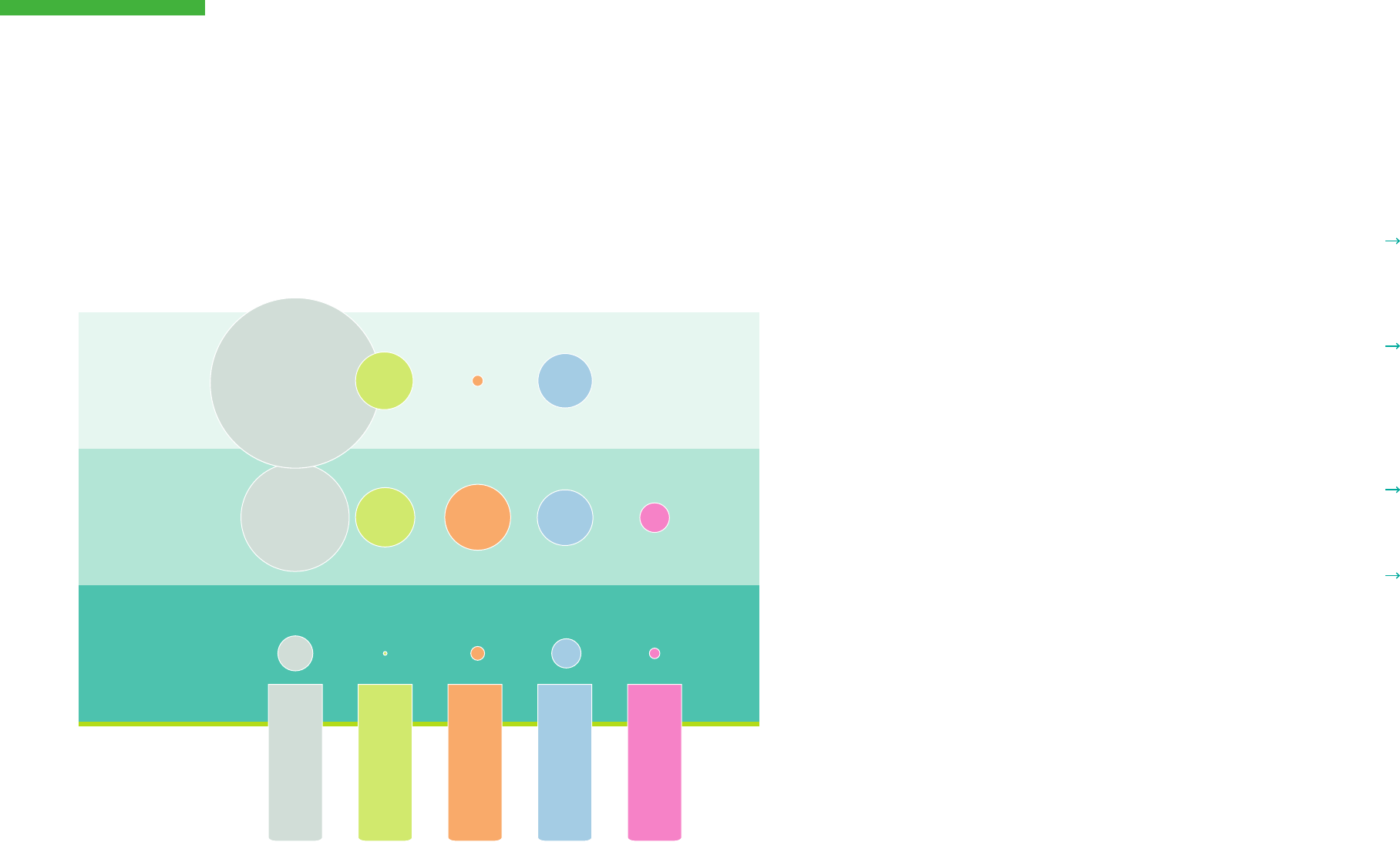

PBII Conceptual model

LGPS funds and other institutional investors

Inter-

linkages

Multiplier

effects

IMPACT INVESTING

Local priorities, needs and opportunities as defined by local authorities, strategic authorities and local stakeholders

SPECIFIC PLACE

HOUSING

SME FINANCE

CLEAN ENERGY

INFRASTRUCTURE

REGENERATION

SCALING UP INSTITUTIONAL INVESTMENT FOR PLACE-BASED IMPACT – THE WHITE PAPER 2021

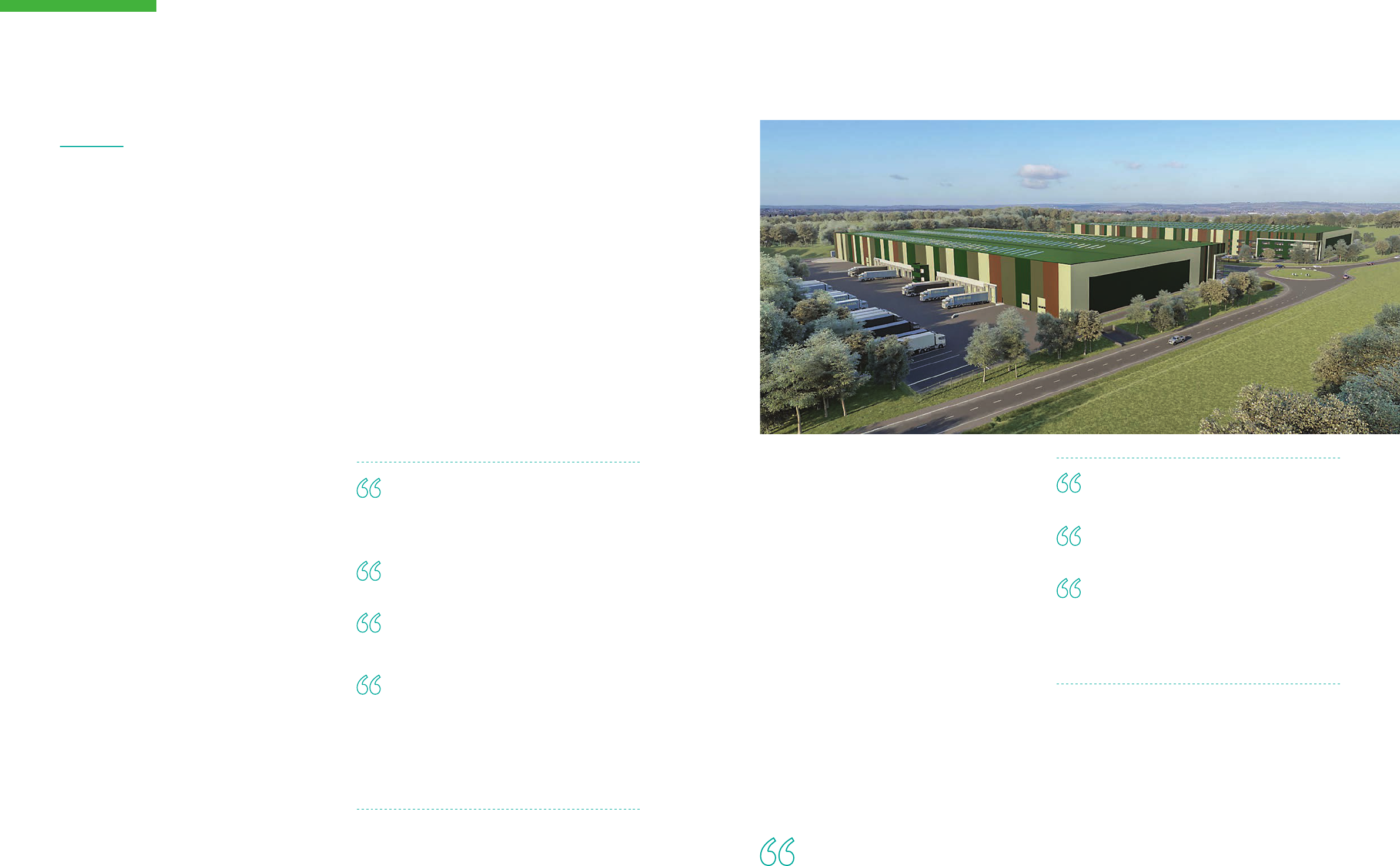

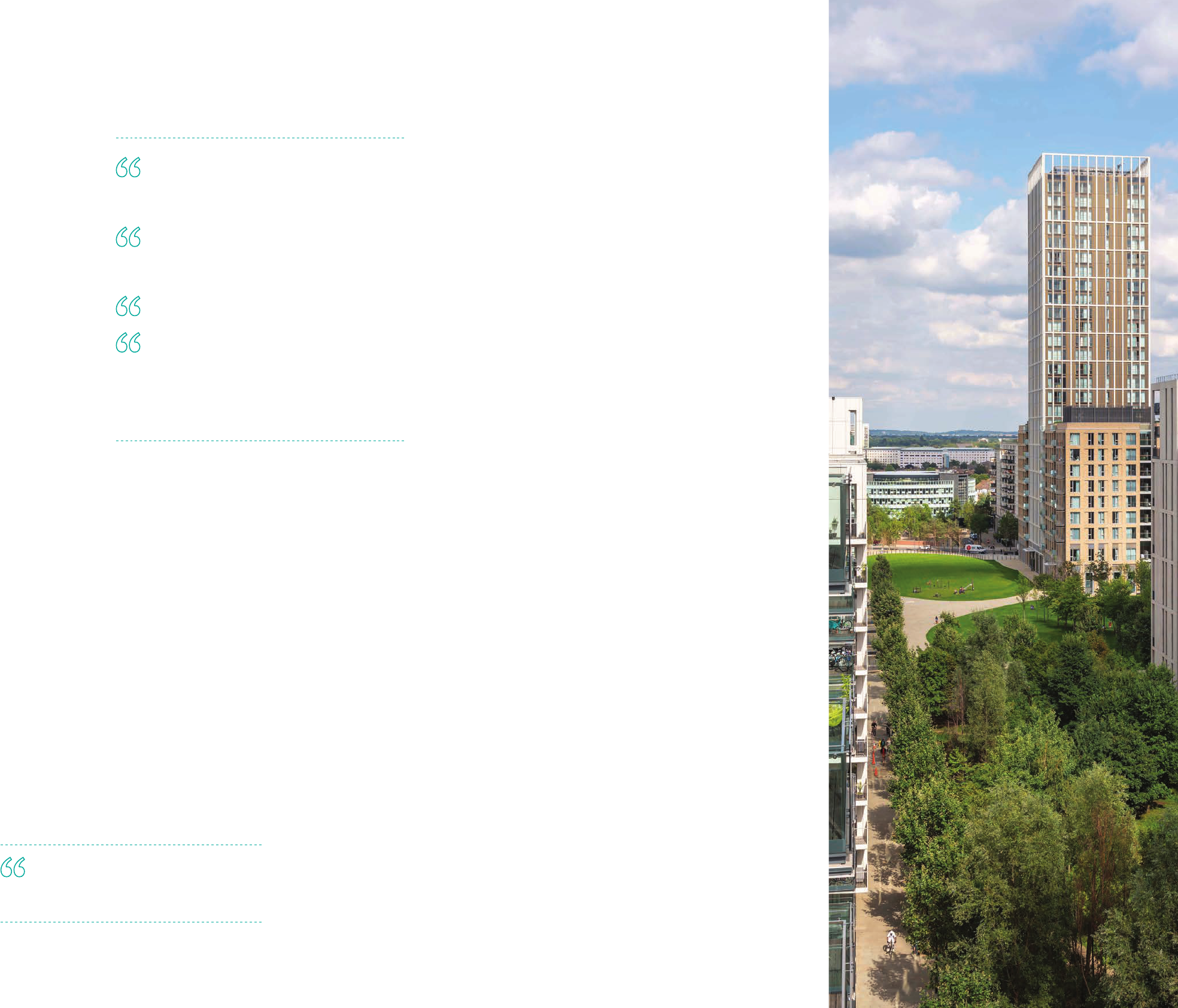

Investment in these sectors is growing due to an

increasing number of funds managed by specialist fund

managers. From 2017 to 2020, the number of private market

funds investing in these sectors increased by 16% from 106

to 123 funds, and the number of public funds increased by

62% from 21 to 34 (see Annex 2 for a list of funds). The

largest growth is seen in investments in residential housing,

including social and affordable housing.

STAKEHOLDER PERSPECTIVES AND CURRENT PRACTICE

There are challenges to PBII but none of these are hard barriers.

The three main challenges are:

Traditional mindsets whereby institutional investors

allocate capital to the global capital markets without giving

full consideration to whether allocations closer to home

could deliver comparable returns and diversification while

benefiting the development needs of local communities.

Fears of conflicts of interest make LGPS managers wary

of being accused of succumbing to political pressures that

undermine their fiduciary responsibility.

Capacity constraints and having the time, expertise and

skills to source and carry out due diligence on PBII

opportunities are the most limiting factors to scaling up

these types of investments.

It appears that the universal requirement to scaling up PBII is an

increase in operational resource across the ecosystem to prepare,

identify and do due diligence on PBII investments, including

building expertise within local authority teams, LGPS investment

teams and consultants. In order to meet this capacity

challenge, we observed approaches we broadly classify as

‘building’ capabilities, ‘buying’ in the skills or ‘borrowing’

resources. Section 4.4 provides examples of how different LGPS

funds have used these strategies to make local investments.

Many UK fund managers expressed frustration that it is easier

to raise capital from foreign pension funds than it is from UK

pension funds. This is in part because these foreign pension

funds are larger with teams that are more experienced in private

market investing who proactively seek out UK opportunities.

In the UK, individual LGPS funds have made PBII-aligned

investments in three ways: direct investments, co-investment

strategies and via third-party managed funds. The vast majority

of capital is invested via third-party funds, hence, fund manager

selection and experience is critical to scaling up PBII. Pension

funds review their managers closely and are often guided by

advisors and consultants.

Many of the fund managers in this space are relatively small,

specialist firms. Those LGPS funds that have a commitment

to PBII have the appetite and resources to engage with and do

due diligence on smaller fund managers. However, the majority

of LGPS funds rely on consultant advice for strategic asset

allocation and fund manager selection and the smaller funds

do not get considered. This pattern tends to lead to bifurcation

in the market. Large fund management firms which are more

able to raise capital are successful but with more traditional

strategies. This contrasts with specialised niche firms which

often have a more impactful strategy or place-led approach

but find it challenging to raise capital.

Consultants perform a gatekeeper role. Hence, getting

consultant buy-in and support is key to scaling up institutional

investment in PBII.

Pension pools are building their capacity and skills in private

markets investing and could potentially also play an important

role in scaling up PBII. There are eight pension pools in England

and Wales which were established as a means for individual

LGPS funds to invest collectively so leveraging scale to

improve investment opportunities and reduce costs.

IMPACT REPORTING FRAMEWORK

Evidencing the achievement of place-based impact is

fundamental to PBII. TGE convened a working group of LGPS

funds, local authorities and fund managers to develop a

common approach to impact measurement, management and

reporting.

We used the PBII pillars to provide a set of common impact

objectives that are relevant from both a local government policy

and investment perspective. We also co-created a reporting

approach that provides a core metrics set to report back on PBII

activity. A key aim was to develop a right-sized and practical

approach to impact reporting that would enable LGPS funds to

communicate with their members in a clear and straightforward

manner about their place-based investment activity.

CALL TO ACTION

We have presented PBII as a new paradigm for institutional

investment using the LGPS to explore its implications for

thinking and doing things differently. We see this paradigm as

potentially having a much bigger reach: the aim should be for

PBII to become a main investment theme in the next decade for

the UK’s leading pension funds.

Successful adoption of PBII through projects that are appropriately

planned, designed and financed would help reduce place-

based inequalities. However, this also requires deploying

the PBII model within existing national strategies that aim to

tackle regional inequalities, such as the Devolution and Growth

Deals, the National Infrastructure Strategy, the Industrial

Strategy, the Climate Change Adaptation Strategy and the

levelling up programmes. PBII can also provide an umbrella

framework for local investment partnerships between

commercial impact investors, local and central government,

social investors (including foundations) and local anchor

institutions, such as housing associations and universities.

Levelling up is about creating this landscape of investment

activity with hundreds of PBII projects underway right across

the country, and with inequality within and between places

diminishing over the next decade. This is what success looks like.

We recommend five areas for action to scale up PBII. We want

to change the traditional investment paradigm and scale

up investment in PBII for the benefit of communities across

the UK. Hence, we need to raise awareness and strengthen

the identity of PBII as an investment approach that could

contribute to inclusive and sustainable development across

the UK, whilst achieving the risk-adjusted, long-term financial

returns required by institutional investors. This requires actions

that raise awareness, increase capacity and competency,

promote place-based impact reporting, connect investors and

PBII opportunities and scale up institutional grade investment

products. Section 6 provides details of these priority areas and

a call for action to all market actors to engage in the PBII agenda.

THE FIVE

CATEGORIES

OF ACTION

RAISE AWARENESS

SCALE UP

INSTITUTIONAL GRADE

PBII INVESTMENT FUNDS

AND PRODUCTS

5

1

2

3

4

INCREASE CAPACITY

AND COMPETENCY

PROMOTE ADOPTION

OF REPORTING ON

PLACEBASED IMPACT

CONNECT INVESTORS

AND PBII OPPORTUNITIES

FINAL REFLECTION

Behind all of the discussion in this white paper is the idea

that if we can get PBII right and launched across the country

– as a top national priority within the build back better and

levelling up agendas – then it is not unrealistic to expect the

UK to approach 2030 as a landscape where place-based

inequalities are becoming a thing of the past. Much of this

report is about ‘getting there’.

If we manage to accomplish this, the UK will be creating

bridges between London and the rest of the country, and

bridges between financial capital and the real economy.

Bridge-building calls for collaboration and a sharing of

money and method, with impact investors of all kinds

working closely with place-based stakeholders from

business, government and community to get things done.

There is a need for mutual learning and understanding, as

we have emphasised throughout this report.

Behind all of the discussion in this white paper is the idea that if we

can get PBII right and launched across the country – as a top national

priority within the build back better and levelling up agendas – then it

is not unrealistic to expect the UK to approach 2030 as a landscape

where place-based inequalities are becoming a thing of the past.

SCALING UP INSTITUTIONAL INVESTMENT FOR PLACE-BASED IMPACT – THE WHITE PAPER 2021

1. Philip McCann, ‘Perceptions of regional inequality and the geography of discontent: insights from the UK’, Regional Studies, 2019.

2. ‘Unequal Britain: attitudes toward inequality in light of Covid’, Policy Institute at King’s College London and UK in a Changing Europe,

February 2021. A key finding of this survey research was that “inequalities between more and less deprived areas (61% of survey

respondents), along with disparities in income and wealth (60%) are seen as the most serious type of inequality in Britain.”

3. HM Treasury, Levelling Up Fund Prospectus, March 2021

4. Since its election in 2019, the Government has made a series of announcements and financial commitments to levelling up in a range

of funds, including the Levelling Up Fund, the UK Community Renewal Fund, the Community Ownership Fund and the Towns Fund.

5. The UK 2070 Commission, Go Big, Go Local: A New Deal for Levelling up the UK, October 2020

6. MHCLG, Local Government Pension Scheme Funds England and Wales: 2019-20 Statistical Release. For Scotland and Northern Ireland

individual pension fund annual reports (2019/2020).

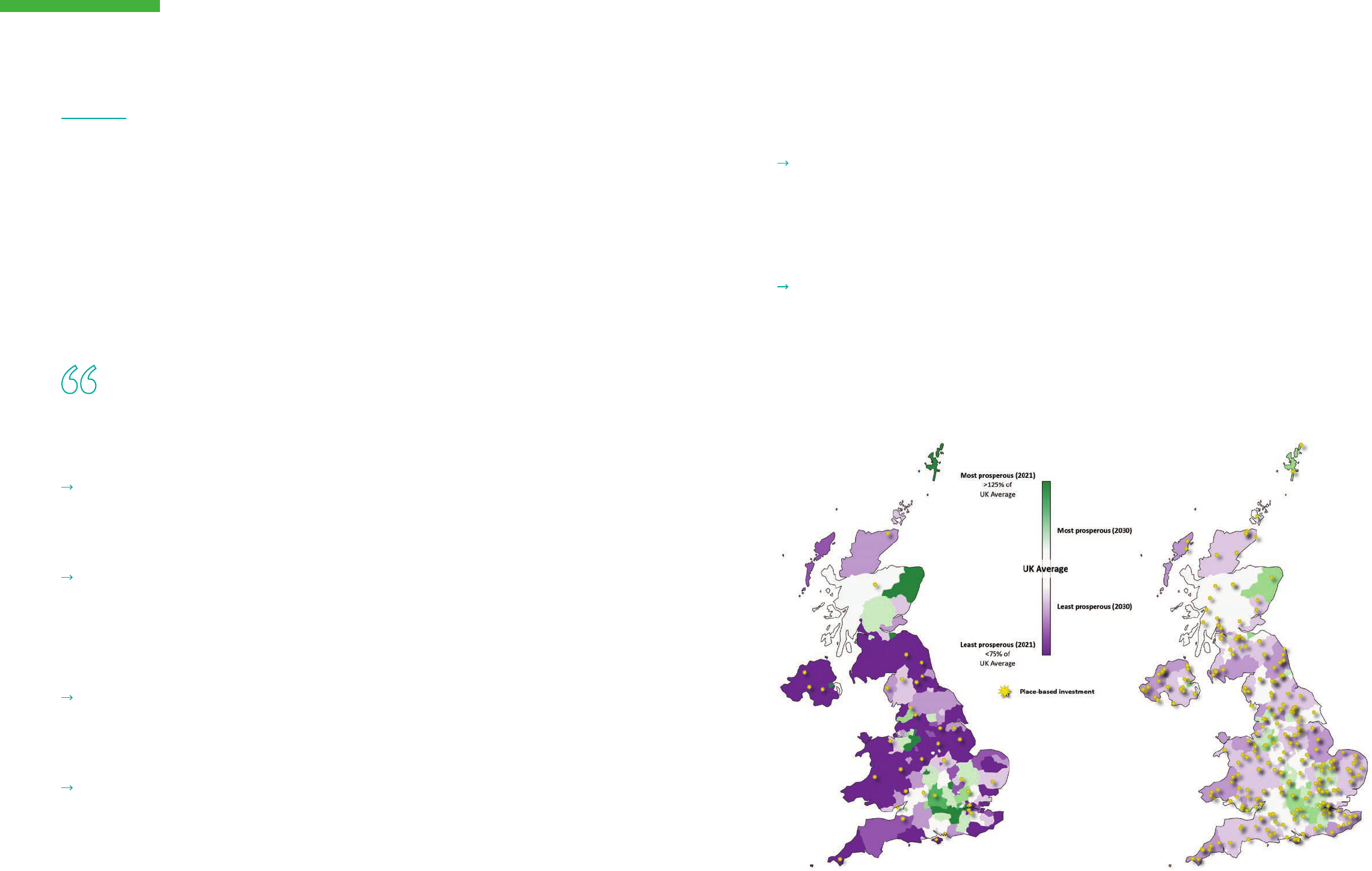

The UK is a country of entrenched place-based inequalities which have persisted for

generations and are more extreme in the UK than most OECD countries (see Chart 1.1).

1

The Covid-19 pandemic and Brexit have combined to move these place-based inequalities

to centre stage in public debate – alongside a search for effective and sustainable ways

of tackling them.

2

Currently only a small fraction of UK pension money is invested directly

in the UK in ways that could drive more inclusive and sustainable development. This

study looks at how to scale up institutional capital, including pension fund investment,

into opportunities that enhance local economic resilience and sustainable development

and create tangible benefits for people, communities and businesses across the UK.

1 INTRODUCTION

Place-based approaches to tackling deep-seated social

and spatial inequalities are now the norm internationally

and they are relatively advanced in the UK.

3

The current

Government’s levelling up policies are consistent with a place-

based approach.

4

With the costs to the nation of levelling

up expected to exceed £1 trillion over the next 10 years, it is

clear public investment will need to be matched by private

investment.

5

This is the rationale for our study, which explores

how a place-based approach, already favoured by public and

social investors, can be extended to institutional investors.

The investor focus of this white paper is the Local Government

Pension Scheme. These pension funds are locally managed by

98 sub-regional Administering Authorities, having assets with

a combined market value of £326 billion as of March 2020.

6

The LGPS has a place-based administrative and membership

geography. Environmental, social and governance (ESG)

integration and alignment with the Sustainable Development

Goals (SDGs) are becoming increasingly important to

investment strategies, and there is a legacy and current

interest in local investing.

We should emphasise, however, that we see place-based

impact investment as a new paradigm or lens for investors

more generally. We envision a confluence of capital flows

from private markets, government programmes and social

investment into local economies and communities. The

levelling up agenda requires this confluence of capital flows,

with institutional investors playing a key role. As such, we

hope this report will be read and acted upon by all institutional

investors and financial institutions.

The project has been led by The Good Economy working in

partnership with the Impact Investing Institute and Pensions

for Purpose. It has been supported by the Department for

Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, City of London Corporation, and

Big Society Capital.

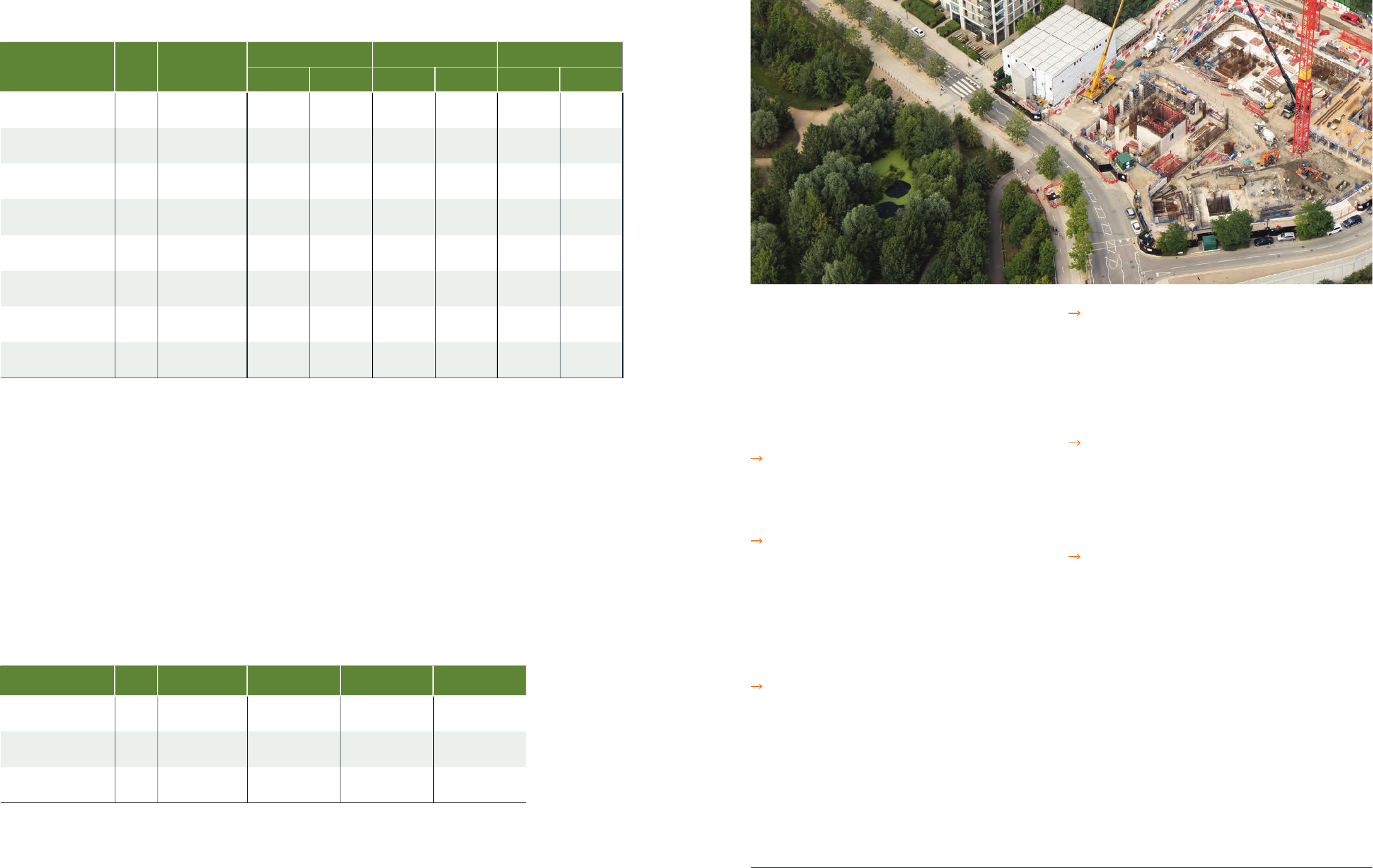

Source: The Good Economy.

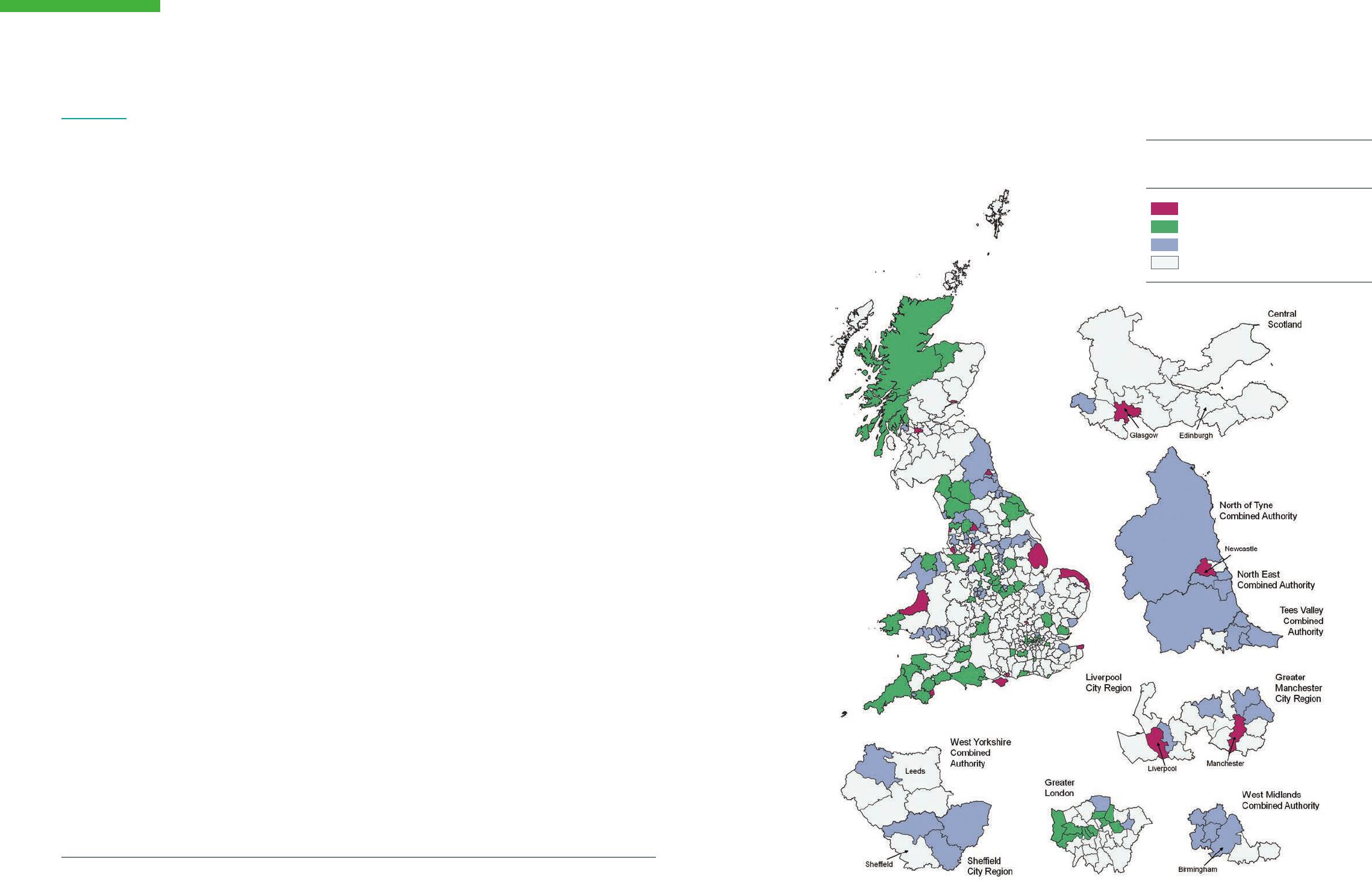

Chart 1.1 Place-based inequality in the UK

Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right (2021).

Recreated from IFS Green Budget 2020: Levelling up: where and how? The Institute for Fiscal Studies, October 2020.

Areas economically impacted by

Covid-19 and considered ‘left behind’

Top quintile Covid-19 and Left-Behind Indices

Top quintile Covid-19 Index

Top quintile Left-Behind Index

Not in top quintile for either measure

SCALING UP INSTITUTIONAL INVESTMENT FOR PLACE-BASED IMPACT – THE WHITE PAPER 2021

This report extends the scope of the LGPS sustainability agenda

from the ‘E’ in ESG to the ‘S’, and from the environmental SDGs

to a wider set of SDGs covering sustainable and inclusive

economic development and decent jobs. As such, PBII offers

a promising route for LGPS funds to achieve SDG benefits on

behalf of their surrounding local and regional communities.

Finally, LGPS funds have a legacy of local investing to build on.

If 5% of LGPS funds were allocated to local investment this

would unlock £16 billion for PBII, more than matching public

investment in levelling up.

Through the course of this research, we found examples of

LGPS funds, both individually and collectively, investing in

projects delivering a positive local impact – notably in the areas

of affordable housing, SME finance, clean energy, infrastructure

and regeneration. These are all areas where PBII could be

scaled up and profiled more strongly for LGPS members and

local community and economy stakeholders. This study

presents ways and means of accelerating this investment

activity and making it more visible and coherent from a local

sustainable development perspective.

1.3 THIS REPORT

Our approach to the study has been collaborative and

consultative throughout, with the research team setting out

to enable LGPS funds and stakeholders and our partners and

sponsors to contribute advice, guidance and practical support

to the project work.

The structure of the report is as follows:

Section 2 outlines a conceptual ‘five-pillar’ model of PBII,

the social and financial case for investment, a mapping of

the stakeholder ecosystem and five traits that define PBII

Section 3 provides a baseline assessment of PBII activity

by LGPS funds

Section 4 analyses stakeholder perspectives on the

challenges and opportunities for PBII, the investment

models used and possible routes to increase institutional

investment flows

Section 5 presents a proposed common approach to

impact measurement, management and reporting

Section 6 synthesises our conclusions and proposes five

action areas to scale up PBII.

7. Taylor, M., Buckley, E. and Hennessy, C. (2017). Historical review of place-based approaches, Lankelly Chase.

8. Centre for Cities, Levelling Up the UK’s Regional Economies, March 2021; Institute for Fiscal Studies, Levelling up: Where and How?, October 2020.

This study explores the potential role of impact investing

in tackling place-based inequalities, given its mission is to

generate positive social and environmental impacts while

providing investors with financial returns.

The PBII Project has set out to answer how impact investing

can, as a global market trend, be purposed to deliver positive

impact at the local level, measured by progress towards a

future of inclusive prosperity and sustainable development.

Similarly, the project asked what a place-based approach to

impact investing – or simply, ‘place-based impact investment’

(PBII) – would look like in practice, starting from the following

definition:

Place-based impact investments are made with

the intention to yield appropriate risk-adjusted

financial returns as well as positive local impact,

with a focus on addressing the needs of specific

places to enhance local economic resilience,

prosperity and sustainable development.

In the sphere of public policy, place-based approaches refer to

the sub-national – for example, regional, local, neighbourhood

– level of economic, social and community development and

service delivery. The UK public policy landscape has been

described as ‘a patchwork quilt’ of place-based initiatives,

mainly anchored by local authorities working together in

cross-sector and regional partnerships.

7

In the commercial sphere of institutional investment, ‘place’

is typically looked at through the lens of country-level

diversification within global portfolios. The PBII Project has

explored the prospect of sub-national portfolio diversification

by institutional investors – with ‘place’ referring to local

and regional economies and communities within the UK. In

other words, ‘place’ in PBII is where these public policy and

commercial spheres intersect.

PBII is a paradigm which positions ‘place’ at the sub-national

level – regions, cities, communities – and enables institutional

investors to engage in the same spatial context, making it

possible for collaboration and shared value creation. The

project has asked: what can place-based stakeholders and

impact investors learn from one another? One area for mutual

learning and knowledge-sharing lies in impact measurement,

management and reporting. This could provide a promising

route for developing targets and metrics for levelling up

policies, programmes and projects.

8

The thrust of this report is to scope out PBII as an opportunity

area where potential synergies between investors and

place-based stakeholders can be used to provide both long-

term positive financial returns and social, economic and

environmental impacts.

The LGPS is one of the largest pools of institutional capital

that also has connections with place-based communities in

all areas of the country. The decentralised geography of the

LGPS and its local investment decision-making powers suggest

it is worthwhile exploring how it could play an important and

distinctive role in PBII.

Further to this, if PBII were to lead to more prosperous local

economies and communities, local authority revenues would

be enhanced. Ideally, PBII would generate a virtuous circle of

good pension fund returns and strong local multiplier effects

that bring inclusive prosperity and sustainability in the long run.

Stronger local economies would also result in greater financial

stability for the local authority members of the pension funds.

This is, of course, an ideal scenario. In the first instance, LGPS

funds have responsibilities to their members as pension fund

managers. Political and financial barriers are also known to

influence the scope of LGPS decision making. Certainly, LGPS

funds do not see themselves as ‘impact investors’ seeking to

meet local development objectives. However, we do know that

the LGPS funds are moving decisively in the direction of ESG

integration and the SDGs, which is evident from their investment

strategies in public listed and private markets.

The levelling up agenda goes hand-in-hand with the climate

change agenda where pension funds already have a strong

focus, including how to build net zero portfolios. Delivering

these two goals together would support a just transition to

a net zero economy that supports green job creation and

simultaneously delivers environmental, economic and social

benefits across the UK.

1.1 PLACE-BASED APPROACH TO IMPACT INVESTING

1.2 WHY THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT PENSION SCHEME?

SCALING UP INSTITUTIONAL INVESTMENT FOR PLACE-BASED IMPACT – THE WHITE PAPER 2021

9. Local Government Association (LGA), Attracting investment for local infrastructure (Guidance), 2019.

10. Isabelle Roland, ‘Unlocking SME productivity’, LSE Centre for Economic Performance, 2020.

Looking at PBII through the lens of these asset classes is a

useful entry point for institutional investors, including LGPS

funds that must achieve commercial returns to meet their

pension fund obligations. Such investments have direct

linkages to the real economy and development processes

and activities that impact on people’s lives and the prosperity

of places, therefore bringing about place-based impacts, as

described below. Our interviews with LGPS funds confirmed

that approaching PBII opportunities that already exist in

sectors within the asset classes they are familiar with is a

helpful approach.

It makes sense to approach PBII through the

lens of asset classes that pension funds are

familiar with e.g. infrastructure, real estate.

– Academic Expert

Investing in place is a hard ask. It is much

easier to have an allocation to affordable

housing that sits within a real estate

allocation and may bring benefits to UK

places that include one’s own backyard.

– LGPS Investment Manager

Start with the asset classes and from there

we can approach how our investments

intersect with place.

– Pension Fund Advisor

Below we describe the nature and types of investments in

these five pillars and their role in delivering place-based benefits

followed by the financial case for investing in these sectors.

Critical to PBII is recognising the interlinkages between these

sectors and how we develop place-based approaches that

bring together multiple stakeholders in more coordinated and

joined-up investment strategies that benefit local people and

places through both their direct and multiplier effects.

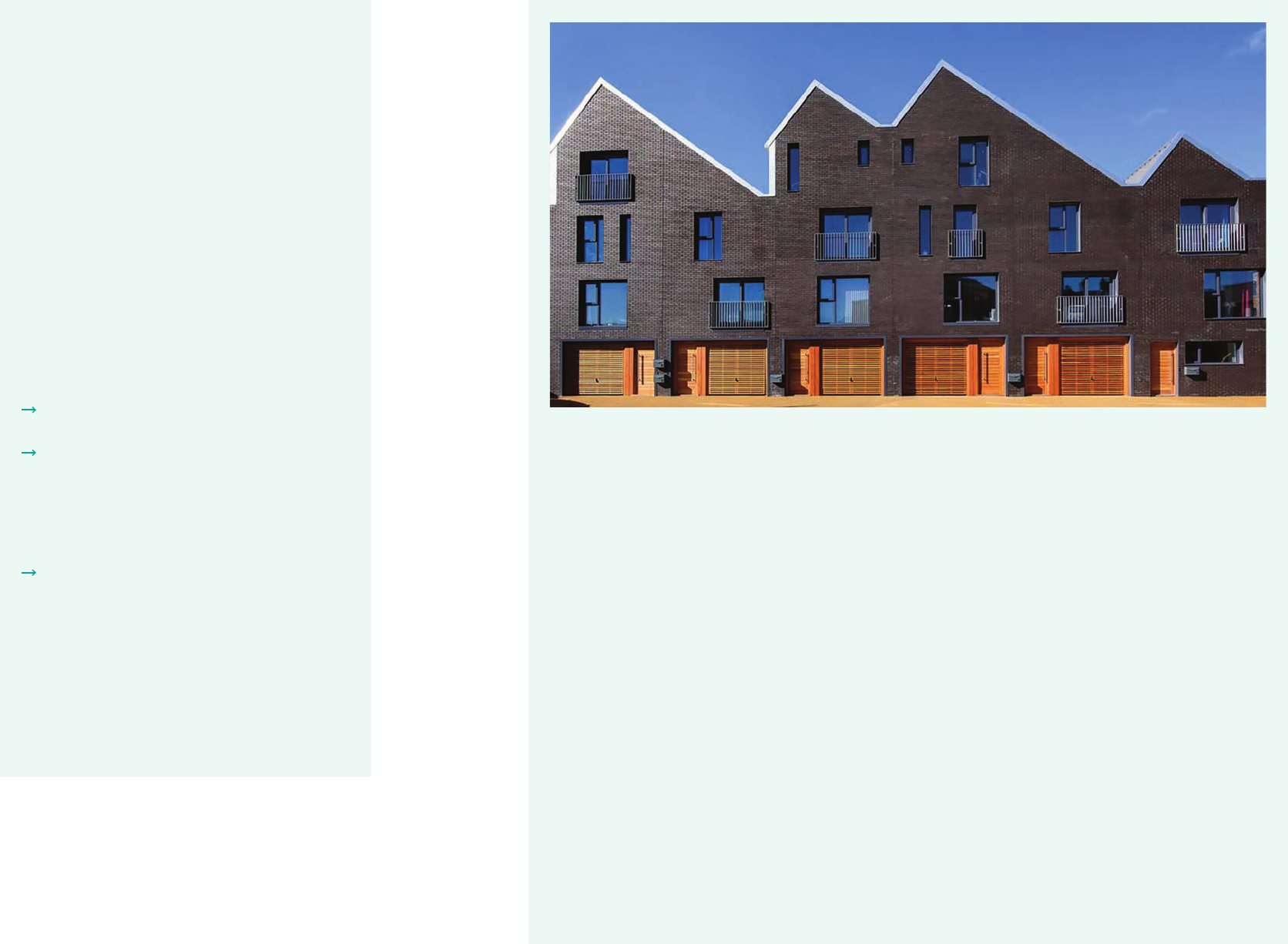

THE FIVE PILLARS OF PBII

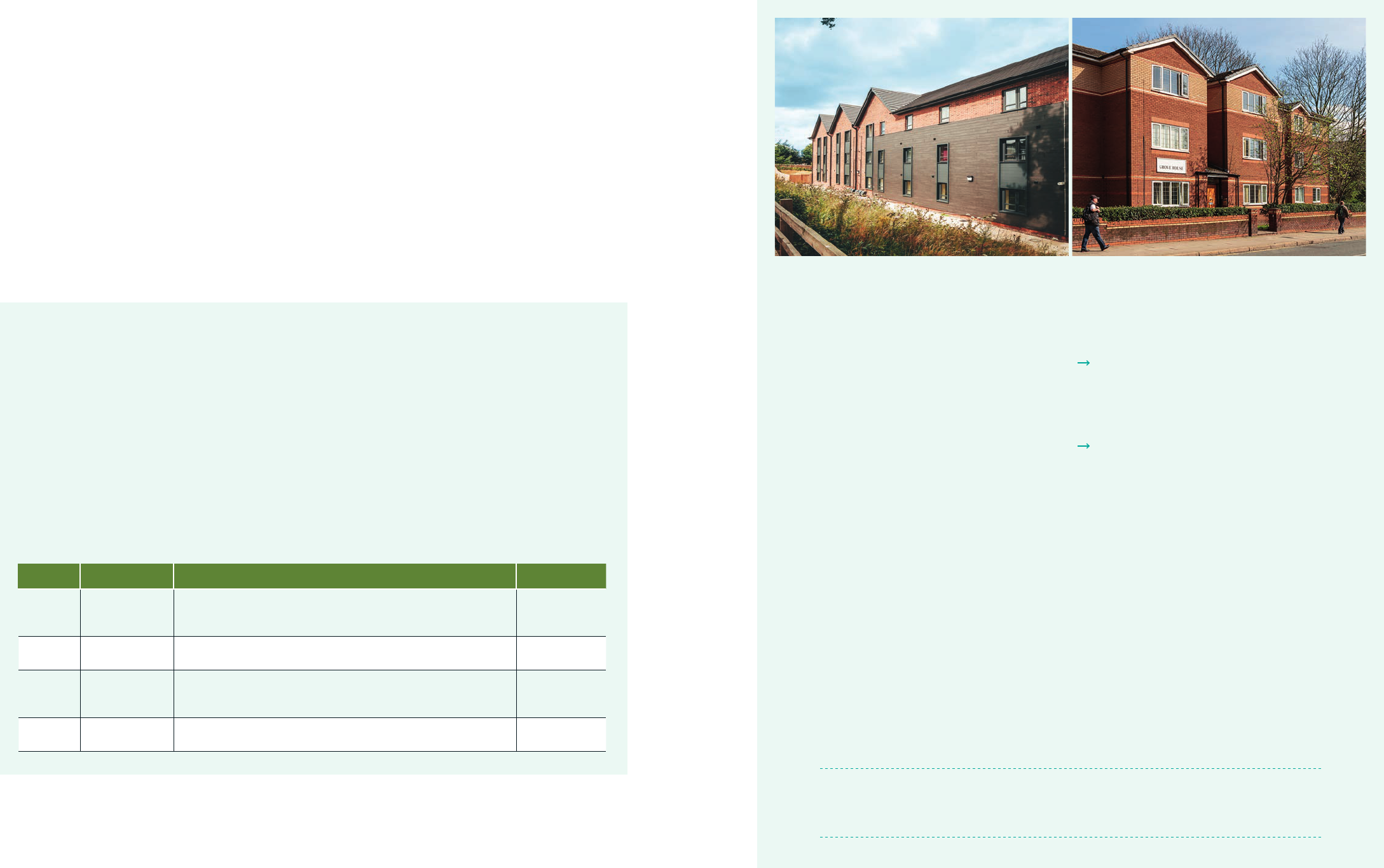

Affordable housing is a cornerstone of community and

economic development, generating health, employment

and community wellbeing benefits. Lack of housing

affordability has reached a crisis level in many UK cities,

such that investing in genuinely affordable housing is a top

priority for PBII. Housing associations are important

providers of affordable housing and recognised as ‘anchor

institutions’ in place-based development and partners for

institutional investors.

Affordable housing investments include social rent,

affordable rent, shared ownership, private sale, private

rent, specialist supported housing, and shared living (e.g.

independent living for older people). Such investments are

typically managed by real estate investment firms as well

as specialist social housing fund managers. Institutional

investors also invest in bonds issued by housing associations.

Small and Medium Enterprise (SME) Finance reflects the

importance of SMEs and social businesses to local

economies and communities. SMEs form the backbone

of local economies and account for more than 60% of

private sector jobs. They play a central role in localised

growth given their spread across high and low wage/skill

sectors and their presence across all communities, towns

and regions. SMEs, including start-ups, are a traditional

focus of local government policy and industrial strategies.

Investing in local SME development is key to inclusive

prosperity and levelling up, particularly investing in growth

sectors which provide quality jobs and support the

transition to a green economy.

10

Social businesses,

including social and community enterprises, play

an important role in more inclusive community-based

development and community wealth-building.

SME finance includes venture capital, debt and private

equity. Investment organisations include SME fund

managers, often investing in specific high-growth sectors,

Community Development Finance Institutions (CDFIs), as

well as specialist social investment intermediaries funding

social enterprises.

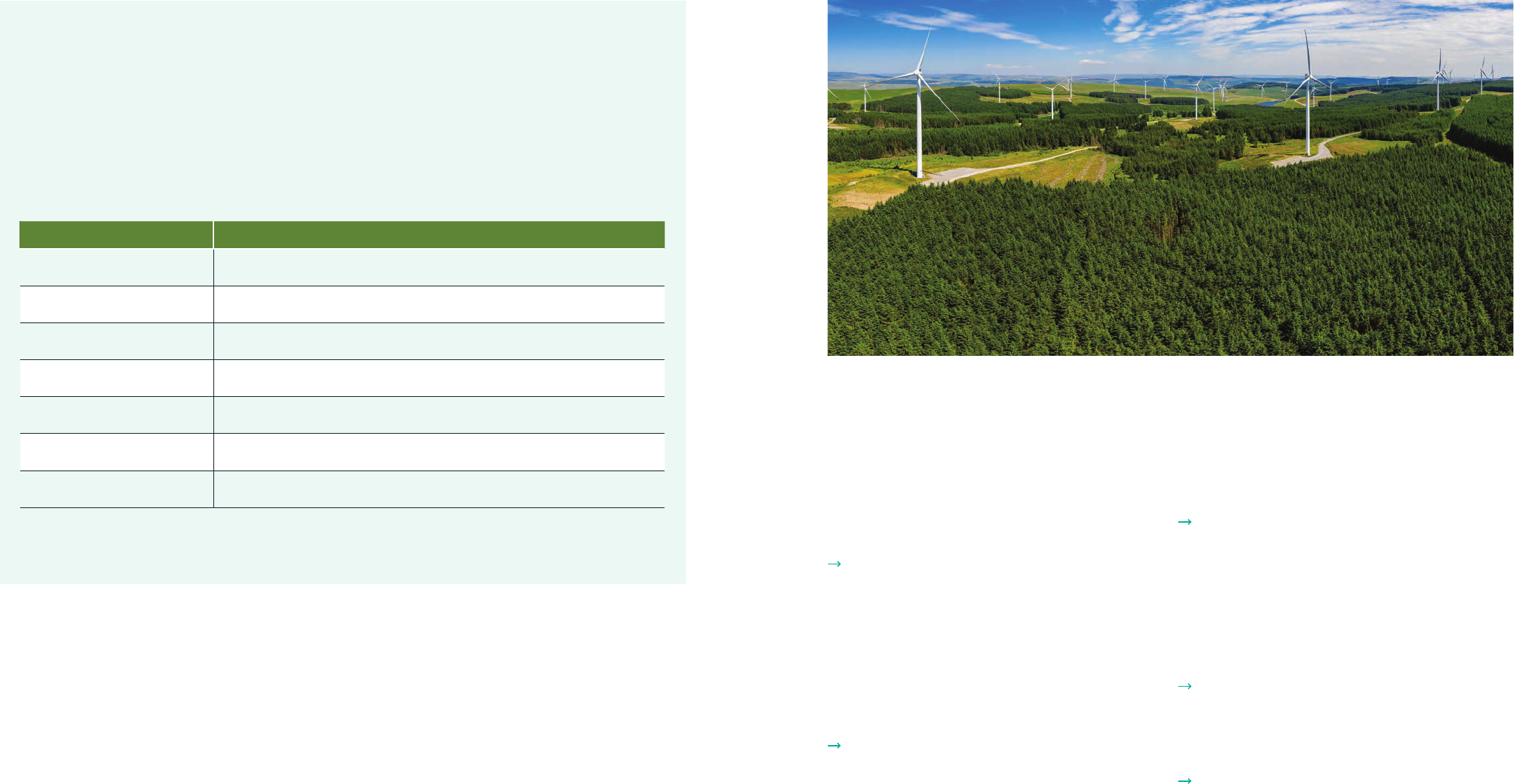

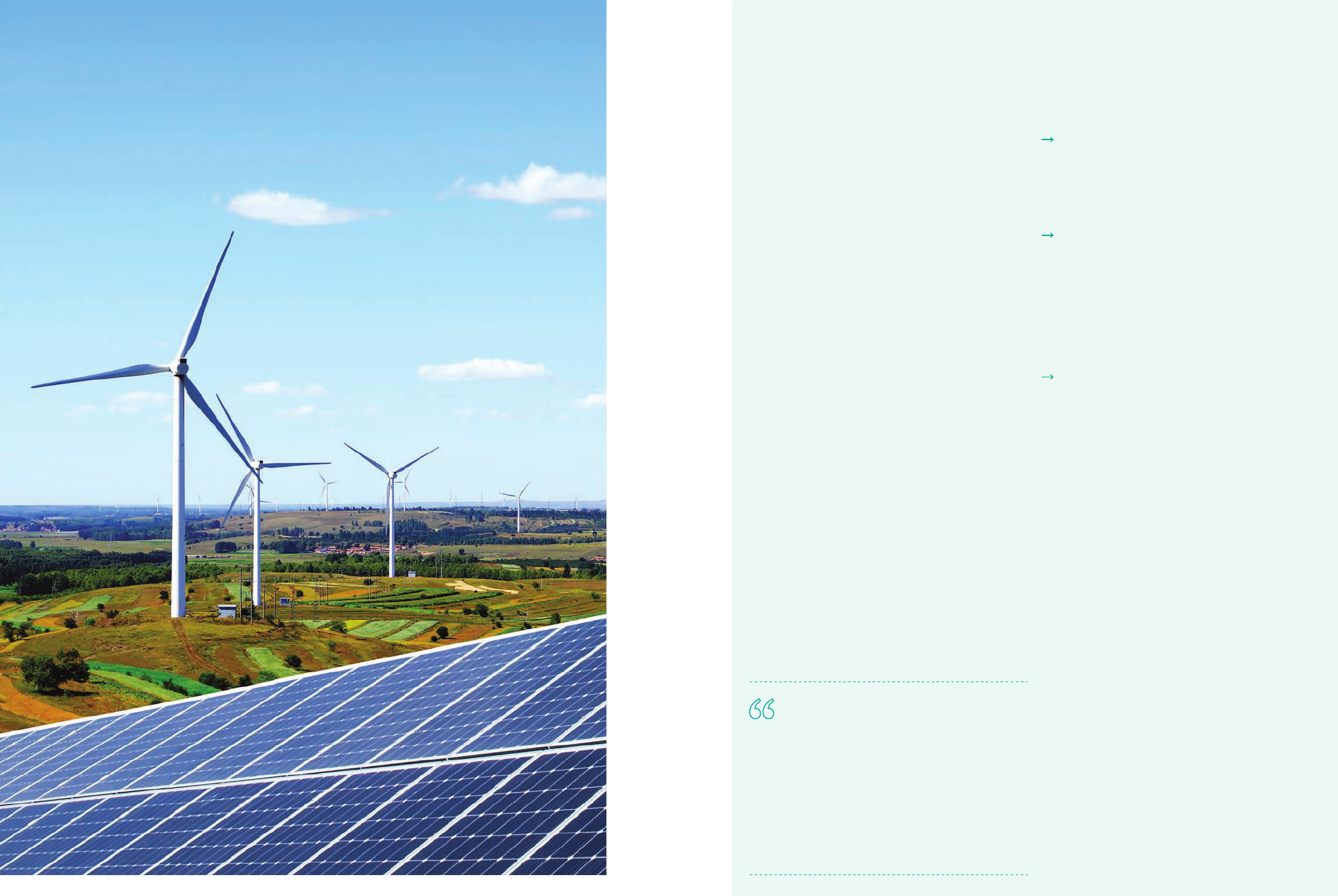

Clean energy and energy efficiency is prioritised in the

Government’s Industrial Strategy – new green industries,

businesses, technologies and jobs – as well as in build

back better policies aimed at renewing and decarbonising

towns and cities. Clean energy has been a focus of place-

based initiatives for decades. It is now a major focus for

institutional investors, including pension funds, who are

tied into commitments to reduce the carbon footprints of

portfolios and meet net zero targets.

Investments include solar, wind and other renewable

energy sources, waste-to-energy, green technologies,

retrofitting and installation of electric car charging points.

Such investments are typically managed by specialist

investment firms.

This section provides a framework for LGPS

funds and other institutional investors to

engage in place-based impact investing

either as something new or to build upon

existing investment activity.

We provide a mapping of the stakeholder ecosystem from

the LGPS perspective showing what types of relationships

and linkages are needed to implement the investment

model successfully. Then we provide data that demonstrate

the strong financial performance of the asset classes that

sit within these five pillars. Finally, we describe five traits

that define and distinguish PBII in order to build a shared

understanding and collaborative approach to its scaling up.

2.1 A CONCEPTUAL MODEL:

THE ARCHITECTURE OF PBII

The conceptual model shown below is intended to provide an

overall picture of the architecture of PBII. As place-makers,

local authorities and their strategic partners ‘reside’ in the

model’s foundation stone. The model positions LGPS funds and

other institutional investors in the capstone.

The five pillars are dual structures. On the one hand, they

represent policy themes or priority areas in local and regional

development strategies. On the other hand, the pillars are

sectors that fall within institutional investment strategies.

The pillars have to bear the weight of investor risk-return

expectations while meeting the inclusive-sustainable development

expectations of local authorities and strategic partnerships.

Successful delivery of PBII should be a win-win game. We can

add other pillars – for example, agriculture and forestry which

are important to rural authorities and LGPS funds.

2 A PLACE-BASED FRAMEWORK

FOR IMPACT INVESTORS

Chart 2.1 The architecture of place-based impact investing

Investing underpinned by impact investing principles and

impact measurement, management and reporting practices.

L

GPS funds and other institutional investors

IMPACT INVESTING

Source: The Good Economy.

Inter-

linkages

Multiplier

effects

Local priorities, needs and opportunities as defined by local authorities, strategic authorities and local stakeholders

SPECIFIC PLACE

HOUSING

SME FINANCE

CLEAN ENERGY

INFRASTRUCTURE

REGENERATION

SCALING UP INSTITUTIONAL INVESTMENT FOR PLACE-BASED IMPACT – THE WHITE PAPER 2021

11. UK Department of Business, Innovation and Skills, ‘Research to improve the Assessment of Additionality’, Occasional Paper 1, October 2009.

12. Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) is a mathematical framework for combining a portfolio of assets such that the expected return is maximised for a given level of risk.

It uses the variance of the asset prices as a proxy for risk. Its key insight is that it is not the asset’s own risk and return which is analysed, but the contribution the

asset makes to the portfolio by also including the correlation of risk in the calculations.

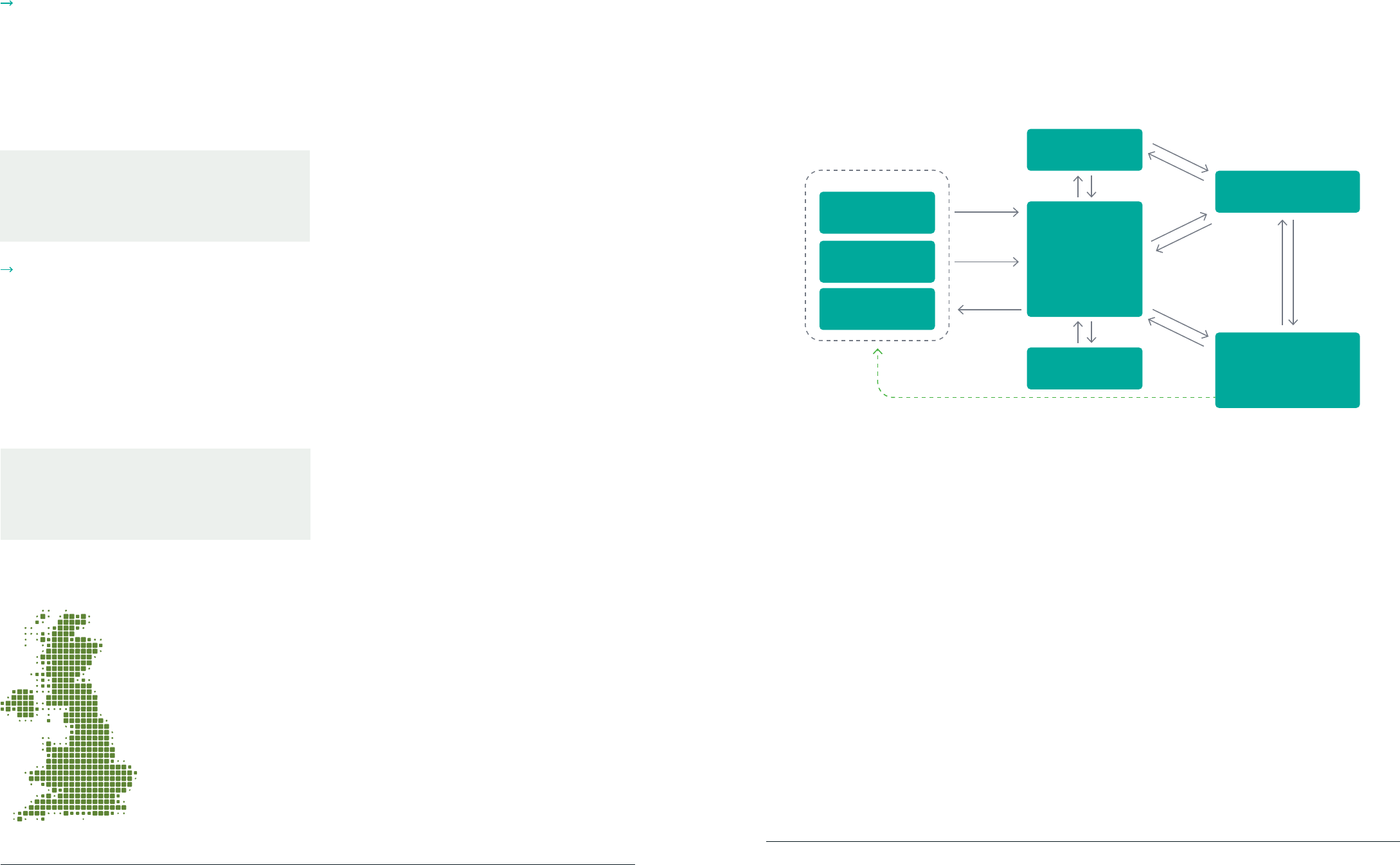

2.2 THE STAKEHOLDER ECOSYSTEM

A core feature of PBII is creating an alignment of interest among all stakeholders in shared impact creation for the benefit of

local places and people. The key stakeholder groups described below all have a role to play in influencing levels of investing for

place-based impact by LGPS funds. They are depicted below showing their sphere of influence and their inter-dependencies. Their

perspectives on the challenges and opportunities for scaling up PBII are provided in Section 4.

Infrastructure investments have a powerful multiplier effect

and play a critical role in supporting local communities and

the local economy. “They can unlock an area’s potential,

enable residents to access new education, skills, and work

opportunities, support local retail and business areas, and

increase the viability of new sites for homes and businesses”.

9

Scaling up infrastructure investment is a central plank of

the Government’s levelling up agenda and a priority for

many local and combined authorities.

Infrastructure investments include transport (such as roads

and bridges), utilities, telecommunications and social

infrastructure (such as schools and hospitals). These are

large-scale, long-term investments in physical (real) assets

managed by specialist investment firms.

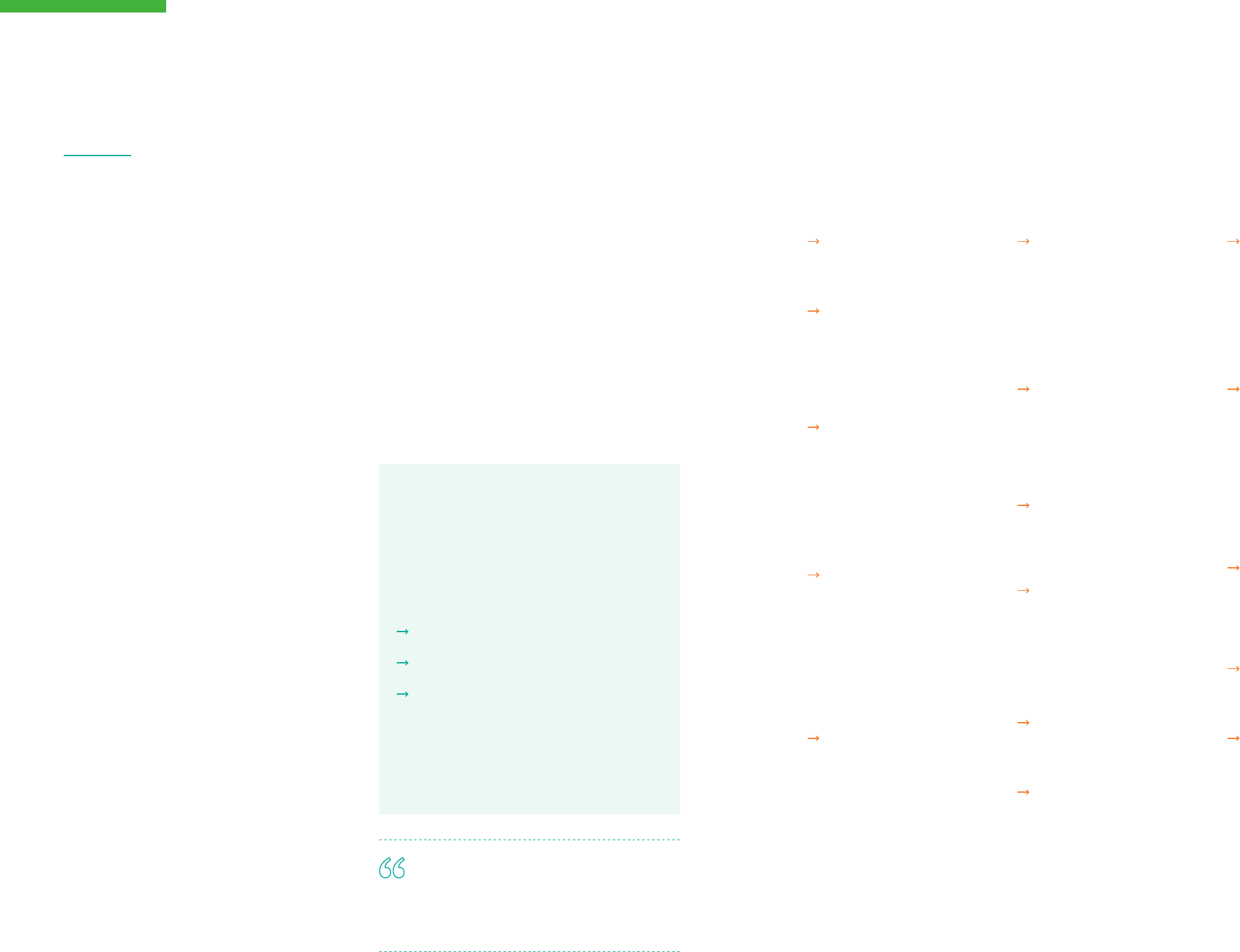

Regeneration here refers to physical development –

from the remediation of contaminated ‘brownfield’ land

to urban regeneration projects – but not the social capital

aspects of regeneration, such as community development

and employment and training. Authorities tend to pursue

a holistic, joined up approach to physical and social

regeneration. Institutional capital can have place-based

impacts by investing in regeneration schemes and helping

to ‘re-purpose’ town centres. Local authorities are already

busy reviving existing assets such as government buildings

and empty offices and high street shops.

Regeneration involves mixed use urban development

schemes, typically including residential, office, and retail

development, as well as improvements to public space

and amenities. Investors include those who fund new

developments and those who acquire properties once built.

Successful investments that constitute PBII are those that

produce positive social, economic and/or environmental

outcomes for specific local communities and economies

as well as appropriate risk-adjusted financial returns for

institutional investors. As such, PBII strategies must be

supported by an adequate evidence base on local needs

and priorities, including constructive engagement with local

stakeholders.

Stakeholder consultation and engagement is indeed

fundamental to PBII. This type of investing is about ‘boots on the

ground rather than eyes on screens’. It also requires developing

impact assessment and reporting systems to measure and

report on positive impacts achieved in relation to place-based

needs and priorities, and to understand and mitigate potential

negative local impacts.

The pillars can unify investors and local authorities by

providing a common set of place-based impact objectives

that are relevant from both a policy and investment

perspective and which foster collaboration and a sense of

shared purpose. See Section 5 for a proposed common impact

assessment framework for LGPS funds, local authorities and

fund managers, including place-based impact objectives.

When assessing place-based impacts, it is important to

recognise that public or private investors may intentionally

target specific places, however the impacts on people and

businesses may fall outside the prioritised geographical areas.

The smaller the area, the greater the probability that impacts

will benefit other areas outside of it. For example, an investment

may be made in a local business but employees may live

elsewhere. These ‘leakages’ have been highlighted in evaluation

studies of additionality in the case of place-based government

programmes.

11

Institutional investors adopting a place-based approach

can learn from the experience of government programmes,

including approaches to impact measurement. See further

discussion and a proposed common approach to impact

measurement, management and reporting in Section 5.

Successful investments that constitute PBII are those that produce

positive social, economic and/or environmental outcomes for

specific local communities and economies as well as appropriate

risk-adjusted financial returns for institutional investors.

LGPS MEMBERS

AND EMPLOYERS

are the central stakeholders

in this ecosystem. The

LGPS is the largest Defined

Benefit (DB) pension scheme

in the UK. Both employers

and employees pay into the

pension scheme which the

LGPS funds have a fiduciary

responsibility to manage on

their behalf. The majority of

scheme members (74%) work

for local authorities, while

around 25% are employed

by other public sector bodies

(such as higher education and

park authorities) or private

sector and voluntary sector

contractor organisations

which have been granted

admitted body status.

LGPS FUNDS

have a responsibility to

manage members’ pension

contributions and to act in

the best interests of scheme

members when managing

pension assets. Historically,

pension fund managers used

a narrow interpretation of

fiduciary duty and focused

on maximising risk-adjusted

financial returns. However,

today, all investment

institutions, including LGPS

funds, are expected to take

into account ESG factors in

making investment decisions

and many have defined

sustainability strategies.

Because the Pension

Committees decide and

oversee the pension funds’

investment strategies, they

play a key role in determining

them.

PENSION POOLS

are potentially important

players in place-based

impact investing. Pension

pools were established

following the Government’s

changes to the LGPS scheme

in England and Wales in 2015.

The aim was to encourage

individual LGPS funds to

pool their assets and invest

collectively, so the LGPS could

leverage its scale to improve

investment opportunities

and reduce costs. There are

now eight pools as shown in

Chart 2.3. Most are currently

prioritising allocations of

assets to core investment

strategies across public

and private markets and will

consider UK allocations as

part of portfolio construction,

including allocations to

sectors that are key for PBII,

particularly clean energy and

infrastructure.

CONSULTANTS

have a major influence

over the strategies and

decisions of many LGPS

funds, particularly the

smaller ones. These

comprise both individual

advisors who directly advise

pension committees, and

consultancy firms contracted

to provide investment advice,

advise on fund manager

selection and provide

portfolio management and

performance monitoring

services. Consultancy

firms tend to view

investment choices from

the perspective of global

financial markets and trends

using modern portfolio

theory

12

and focus research

and recommendations on

mainstream funds where they

expect broad applicability

and high client demand.

To date, they have shown

limited interest or appetite to

apply a place-based lens or

encourage impact investing.

FUND MANAGERS

are critical players in the

ecosystem as they manage

funds on behalf of the LGPS

funds and pension pools and

make decisions as to which

individual investments are

made into companies or

projects. Their activities are

based on objectives set by

the LGPS funds and pension

pools. Key to place-based

investing is finding and

selecting fund managers with

aligned place-based impact

objectives and the specialist

knowledge and capacity to

originate and make financially

sound investments. Currently,

it is the fund managers

selected directly by LGPS

funds that are most engaged

in place-based investing.

We analyse the state of the

market and types of fund

management models in

Section 4.

Chart 2.2 A Mapping of stakeholders

Source: The Good Economy.

CONSULTANTS

LOCAL REGION

MEMBERS IN RECEIPT

OF PENSIONS

ACTIVELY CONTRIBUTING

MEMBERS

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

EMPLOYERS

PENSION POOLS

FUND MANAGERS

PLACEBASED INVESTMENTS

Local government, residents,

local businesses and local

organisations

LGPS FUNDS

LOCAL BENEFITS AND REVENUES

Employer

pension

contributions

Pension

payments

Investment strategy and

manager selection advice

Individual

pension

contributions

Investment

Returns

Investment

Returns

Investment

Returns

Investment

Returns

SCALING UP INSTITUTIONAL INVESTMENT FOR PLACE-BASED IMPACT – THE WHITE PAPER 2021

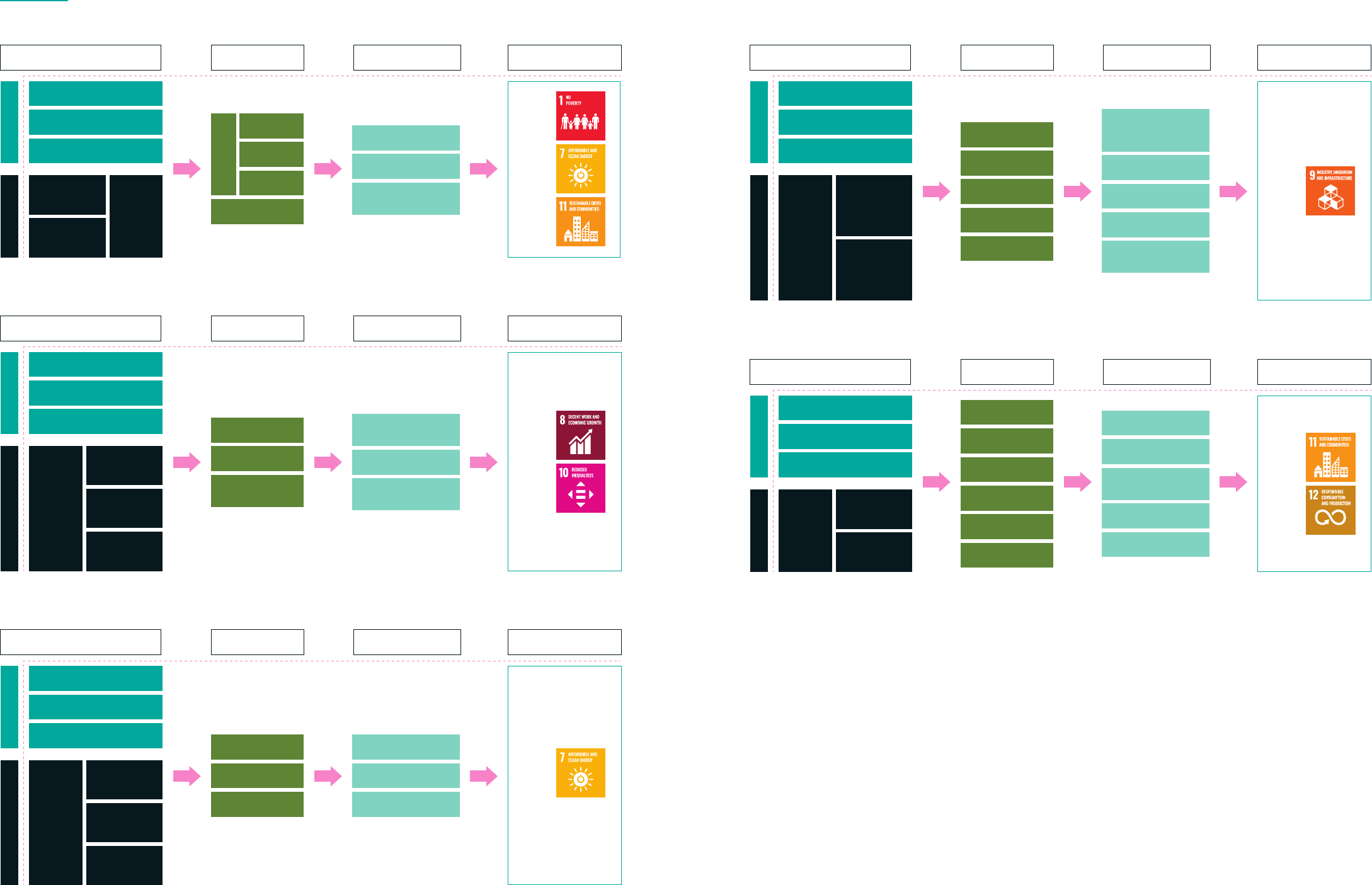

2.3 THE FIVE TRAITS OF PLACE-BASED IMPACT INVESTING

The focus of this report is on how to scale up institutional investment in ways that deliver tangible benefits for local

people and places in order to achieve more inclusive and sustainable development across the UK. But what defines

and distinguishes place-based impact investing?

HERE WE BUILD ON OUR DEFINITION AND CONCEPTUAL MODEL TO IDENTIFY FIVE TRAITS THAT CHARACTERISE PBII:

Source: The Good Economy.

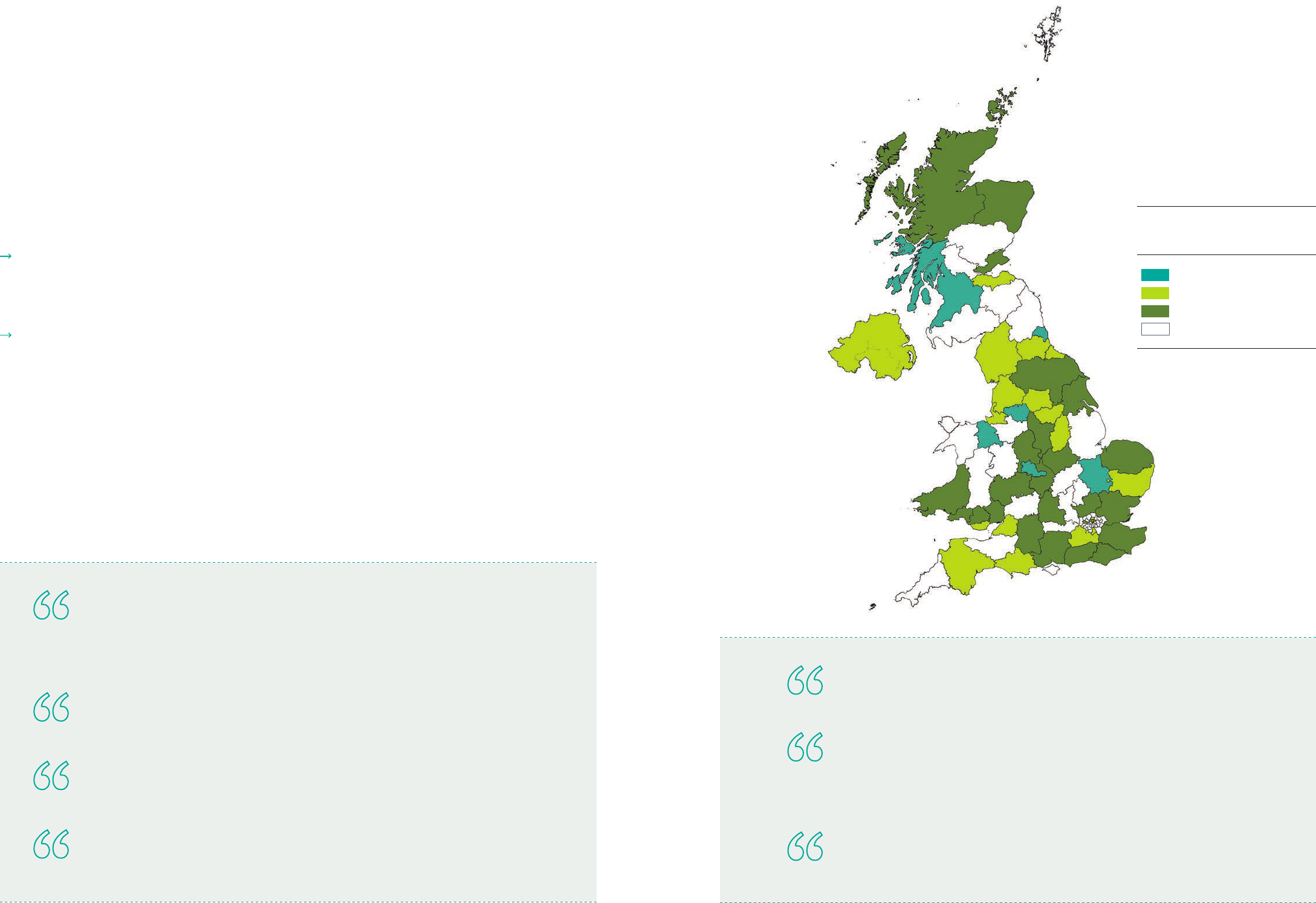

Contains OS data © Crown copyright

and database right (2021).

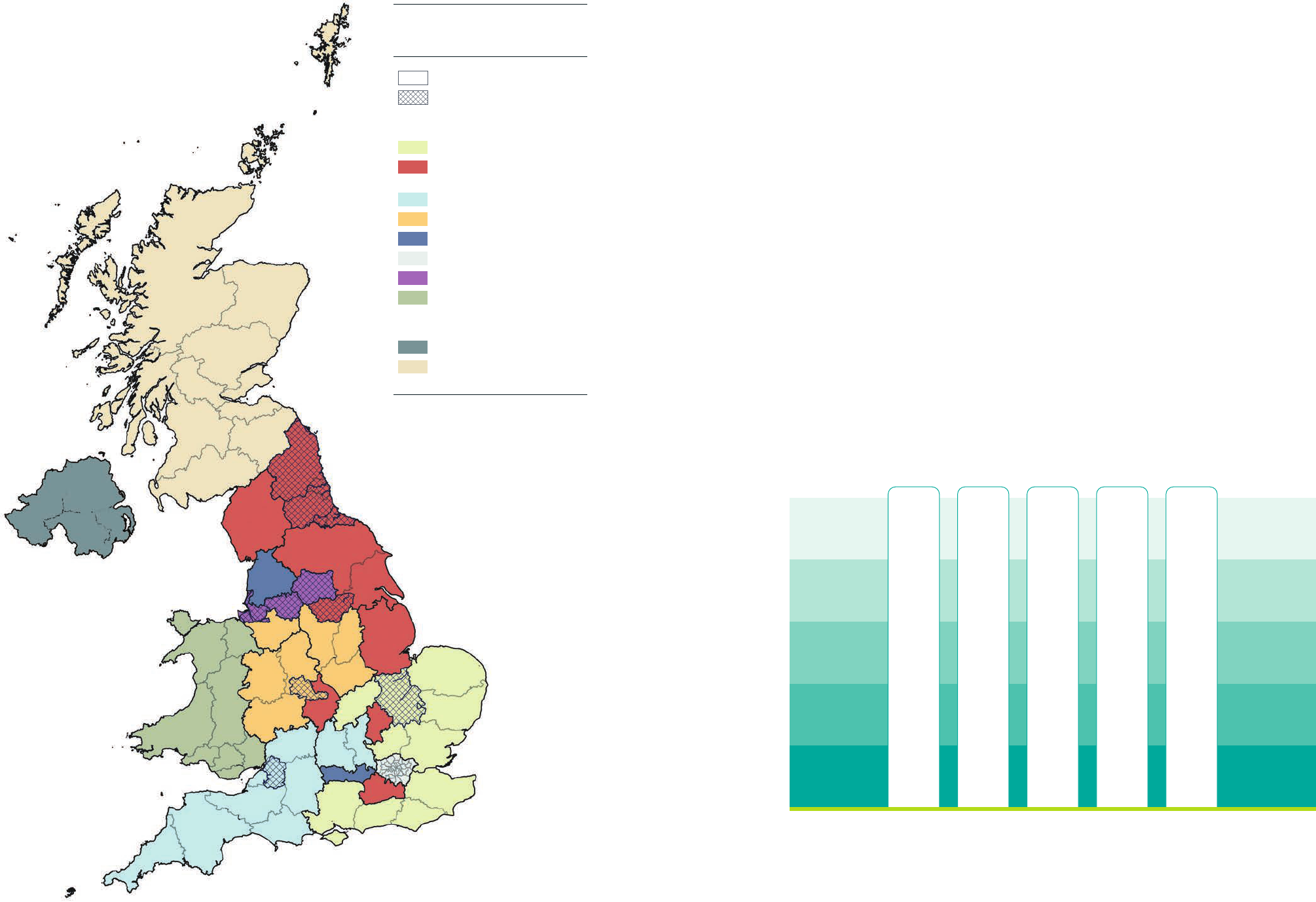

The geography of the UK’s Local

Government Pension Schemes

Local Government Pension Fund

Combined Authorities

Pension Pools

The ACCESS Pool

Border to Coast Pensions

Partnership

Brunel Pension Partnership

LGPS Central

Local Pensions Partnership

London CIV

Northern LGPS

Wales Pension Partnership

Non-Pooled Schemes

Northern Ireland

Scotland

1

First, PBII has a clear intentionality to achieve a positive

impact. Intentionality is a key characteristic of impact

investing. Typically, intentionality is defined in relation to

addressing a defined social or environmental need. PBII investors

need a bifocal lens – focusing on both ‘place’ and ‘impact’

is necessary. Intentionality in PBII should be geographically

bounded – where you are seeking to create a positive impact

is defined, alongside the types of social and/or environmental

outcomes to be achieved. Such intentionality can be articulated

by having impact objectives as well as financial objectives

within an investment strategy. Section 5 proposes a common

set of place-based impact objectives and an approach to

impact measurement, management and reporting.

2

Second, define place. Currently, the vast majority of LGPS

capital is invested in global funds and large multinational

companies in the listed markets and only a small fraction

is invested directly in the UK’s real economy. PBII is about

directing more capital to the UK and its local areas and regions

using a place-based lens. Effective PBII needs to consider the

cross-cutting nature of ‘place’ and ‘sectors’ (see Chart 2.4).

The target geography may differ by sector. For example,

infrastructure investments may focus at the UK level, whereas

SME investments may be targeted to a local area or region.

How LGPS investment is allocated geographically is analysed

in the next section. A PBII approach is focused on the sub-

national level – investing in ways that benefit specific local

areas or regions.

Chart 2.4 The intersection of place and sector

Source: The Good Economy.

National

Global with

national

exposure

Regional

Sub-Regional

LGPS Area

Sectors (Drivers of Impact)

Scale of Place

HOUSING

SME FINANCE

CLEAN ENERGY

INFRASTRUCTURE

REGENERATION

Chart 2.3 The geography of the UK’s

Local Government Pension Schemes

SCALING UP INSTITUTIONAL INVESTMENT FOR PLACE-BASED IMPACT – THE WHITE PAPER 2021

Return (% pa)

14. Fig. 15 PIRC (2020), Local Authority Pension Performance Analytics 2019/20.

15.Preqin (www.preqin.com) is a company that provides financial data, information and analytical tools for alternative assets.13. See PIRC (2020), Local Authority Pension Performance Analytics 2019/20.

Fund manager selection is important. The vast majority

of pension fund assets are managed by third-party fund

managers (see Section 4). The latest PIRC review notes that:

...the move into alternative assets has had

many positive benefits for funds but the

difference in manager skills has brought wide

differences in returns achieved.

– PIRC Review

This highlights that in contrast with index trackers and

traditional traded assets, the ‘alpha’ created by the fund

manager is variable and requires an assessment of the

manager themselves – not just the market beta.

Using the same approach, we sought to assess if the returns,

and relationship of returns to volatility are as compelling

within the UK as the PIRC asset class analysis which is based

on global portfolios.

FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE ANALYSIS

OF RELEVANT KEY SECTORS IN THE UK

We collected data on UK listed equities investing in these

key sectors which we referred to as ‘public markets’, as well

as ‘private market’ unlisted funds. A particular challenge in

assessing the market returns for UK investments in these

sectors is paucity of data. Due to financial regulation and

reporting requirements, there is far better financial reporting

and information in public markets. Private markets are

notoriously opaque compared to public markets. We used

Preqin to access available private funds data, which is a well-

recognised source of information for private funds.

15

PUBLIC MARKETS

The UK FTSE All-Share includes around 600 stocks and

represents approximately 99% of the UK market capitalisation

of equities. We identified 69 shares of operating businesses

and listed funds, including property (Real Estate Investment

Trusts or REITs) and Venture Capital Trusts (VCTs), which invest

in eight sectors relevant to the PBII pillars in the UK.

We then compared the return and risk characteristics of

these sectors versus the FTSE100. We analysed the returns

over the time periods highlighted in chart 2.6, then compared

these returns to the returns on the FTSE100 overall as a

benchmark over that same time period. The figures in green

are comparatively higher than their counterparts in red.

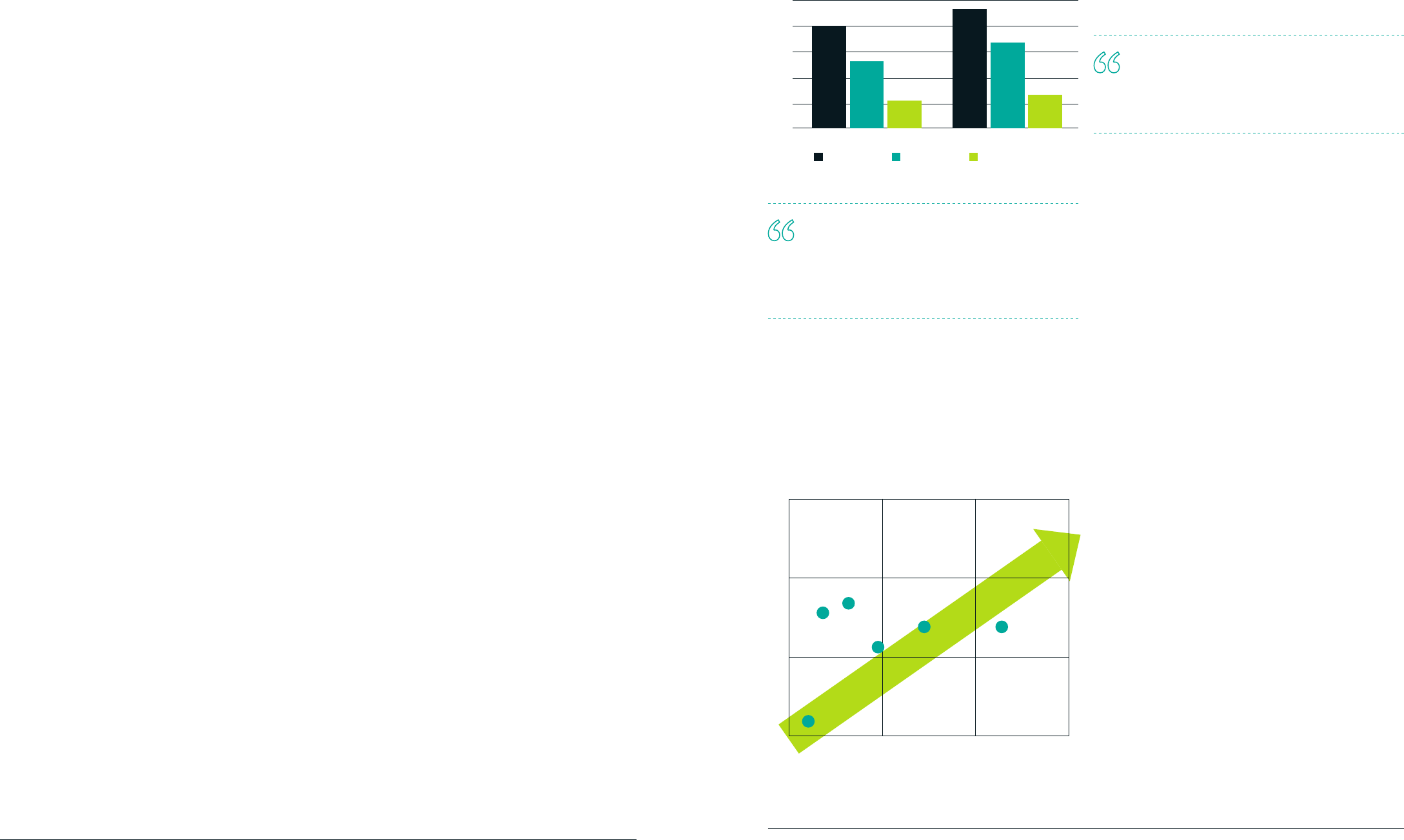

Property and alternatives have delivered

better levels or return, when adjusted for

the volatility, than might be expected whilst

equities have delivered a less efficient level

of return.

– PIRC/LAPPA

Looking to the risks, the PIRC review considers the risk and

return track record of the LGPS funds, using volatility as the

established measure of risk. The chart below from the report

shows that return for a unit of risk is highest for alternative

assets (private equity, hedge funds and infrastructure) and

property. This provides a compelling financial case to invest in

these asset strategies.

14

3

Third, engage with stakeholders. Effective stakeholder

engagement is a core trait of PBII. We regard PBII as

aligning with and supporting locally-defined development

objectives and priorities. It is the role of local and combined

authorities to determine strategic development plans and

these bodies should be regarded as key stakeholders at a

strategic and project planning level. For individual projects or

investments, stakeholder engagement should be widened to

include all relevant local stakeholders in the project planning

and design and how an investment can maximise local

benefits, and mitigate any negative risks.

4

Fourth, a hallmark characteristic of impact investing

is impact measurement, management and reporting.

For PBII, impact creation needs to be properly mapped and

measured. Hence, we need to know the geographical locus of

these impacts – ‘where’ is the next frontier of impact investing,

from where the capital originates to where it is deployed for

the benefit of people in places. Our approach to PBII impact

measurement, management and reporting is presented in

Section 5.

5

Finally, collaboration is critical to PBII. Currently, there

is often a fragmentation and lack of alignment in

decision-making across different stakeholders. Silos and

poor alignment also exist within organisations, including

government. For example, while one local government

department may be focused on social issues and how to

invest more in underserved areas, another department will be

looking at land and property development from a commercial,

revenue-generating perspective. The same applies to

investment firms. For example, firms may have teams

investing in real estate, another in infrastructure, and another

in private equity, all investing in the same places. To optimise

their impact in a specific place, coordination across teams is

necessary. Such conflicts and lack of alignment can be solved

by acknowledging shared impact goals and taking a more

place-based approach to investing.

2.4 THE FINANCIAL CASE FOR

INVESTING IN THE ‘FIVE PILLARS’

There is a clear sustainable development case to be made for

investing in the ‘five pillars’ as described above, but what about

the financial case? All pension funds (including LGPS funds)

have a primary purpose of managing and paying out pensions,

hence, their investments need to deliver the financial returns

that will enable them to fulfil this purpose. The PBII Project

carried out original research that found UK investments within

our PBII pillars can deliver risk-adjusted returns in line with the

financial return expectations of pension funds. The analysis is

presented below.

LGPS INVESTMENT APPROACH

Pension funds (including LGPS funds) are long-term investors

with liabilities up to 30 to 40 years in the future. They tend to

follow a traditional investment approach to build a diversified

portfolio across asset classes that will deliver the financial

objectives of the fund. When setting strategy, the LGPS fund

will take into account the expected level of return and the risks

associated with each asset.

Furthermore, the correlations of the asset returns are assessed

such that the assets demonstrate low correlations with each

other, yet overall deliver good portfolio returns. Conventionally

the volatility of the returns is used as the key determinate of

this risk, and diversification is used to reduce the correlation

between assets and therefore the volatility of the portfolio.

Therefore, there is an expectation that the more volatility that

is accepted, the higher level of return should be delivered.

This approach is the bedrock of Modern Portfolio Theory and is

addressed below when considering the financial case for PBII.

Asset allocations are generally reported as equities, bonds,

cash, property and alternatives. The majority of LGPS assets are

invested in equities (55%) and bonds (20%).

13

The PBII Project is interested in investments which will typically

fall within what is described as ‘alternatives’ or property.

Alternative assets refer to investments falling outside the

traditional asset classes commonly accessed by most investors,

such as stocks, bonds, or cash investments. Due to the alternative

nature of these, such investments are often less liquid.

According to the latest annual review by the Pensions and

Investment Research Consultants (PIRC), the allocation by local

authority pension funds to alternative assets has doubled over

the last decade to reach the current average level of 11% of

assets. Funds have diversified away from equities in an attempt

to reduce volatility. The move into these asset classes has

brought positive financial returns, with private equity delivering

the best performance (see Chart 2.5).

Chart 2.5 Longer term performance of alternatives

Chart 2.6 Asset class performance – 10 years (2010-2020)

Private Equity Infrastructure Hedge Funds

15

12

9

6

3

0

3 years 5 years

% pa

Volatility (% pa)

Alternatives

Total Assets

Equities

Cash

Bonds

Property

15

10

5

0

0 5 10

15

Source: PIRC 2020.

Source: PIRC 2020.

SCALING UP INSTITUTIONAL INVESTMENT FOR PLACE-BASED IMPACT – THE WHITE PAPER 2021

16. PIRC (2020), Local Authority Pension Performance Analytics 2019/20.

A further observation is that private market funds are not

providing accessible data regarding the attractiveness of their

sectors – leading to their exclusion from studies on asset

allocations. This is a well-known issue for private funds which

consequently fall into the alternative asset space. Scaling up

PBII in private markets may require greater disclosure.

FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE ANALYSIS CONCLUSIONS

The results of the research suggest:

Investments in key UK sectors that align with our PBII

pillars provide stable, high, long-term returns and low

volatility versus other mainstream asset classes. As such,

these sectors appear very well suited to LGPS investment on

a purely fiduciary basis.

The universe of assets is, however, comparatively small

and often in the private markets, suggesting manager

selection and deeper understanding of the risks is

demanded of the LGPS and other interested institutional

investors.

In addition to these findings, these assets arguably possess

financial characteristics which are attractive to pension funds,

including:

The cashflow nature of the underlying assets. Investments

in most of these sectors are generally in real assets, such

as housing and infrastructure, so can also provide income

streams given they are underpinned by revenue generating

models. These returns are often inflation-linked, providing

a good match for inflation-linked pensions. As pension funds

mature and members enter retirement, the funds have an

increasing need for income generating assets.

Diversification

“through the cycle”. These assets are also

often underpinned by revenue streams which are either

government guaranteed or (through social transfer

payments) countercyclical. An example is social housing,

where demand increases in recessionary circumstances.

This suggests investments in these assets would provide

even further diversification benefits than are apparent in the

analysis above when considered through the cycle.

These assets are generally illiquid which often command

higher returns. LGPS liabilities are very stable and long-term,

hence the matching with illiquid assets may offer the funds

access to better returns. This is particularly pertinent when

contrasted with the high levels of investment by LGPS funds

into highly liquid Global Equity Trackers (currently c.20%

16

of

all LGPS assets).

More data is available privately. Many private funds do

provide performance data which is not available publicly

for a study such as this but may be made available to

investors and consultants. Therefore, a wider dataset

from the industry (LGPS funds, consultants or advisers)

supplementing this analysis would facilitate greater

understanding of the risk and return trade-offs.

This section would therefore conclude that on a purely risk

versus return basis, PBII assets can provide good investment

opportunities and should be considered as part of an asset

allocation perspective. Section 3 of this report goes on to

investigate further to what extent these allocations exist.

Source: Based on Bloomberg data, analysed in partnership with Centrus.*# is the number of constituent assets.

PRIVATE MARKETS

Sourcing private market data was more challenging due to the

limited level of consistent financial reporting by fund managers.

Private funds often simply publish the financial returns for

the end of their investment period, which disguises the asset

volatility and is not directly comparable to periodic returns (as

analysed in the traded assets in the previous section).

A total of 68 funds were identified that were aligned to our PBII

pillars and had a UK focus. However, many of these funds do not

report performance data on a consistent and regular basis,

nor in a format that is easily comparable to a simple quarterly

return figure.

Notwithstanding the data limitations, we were able to produce a

financial performance analysis as shown in Chart 2.8. No proxy

benchmark was used as a comparator. However, the relative

returns can be observed over similar timeframes using the

public market analysis above.

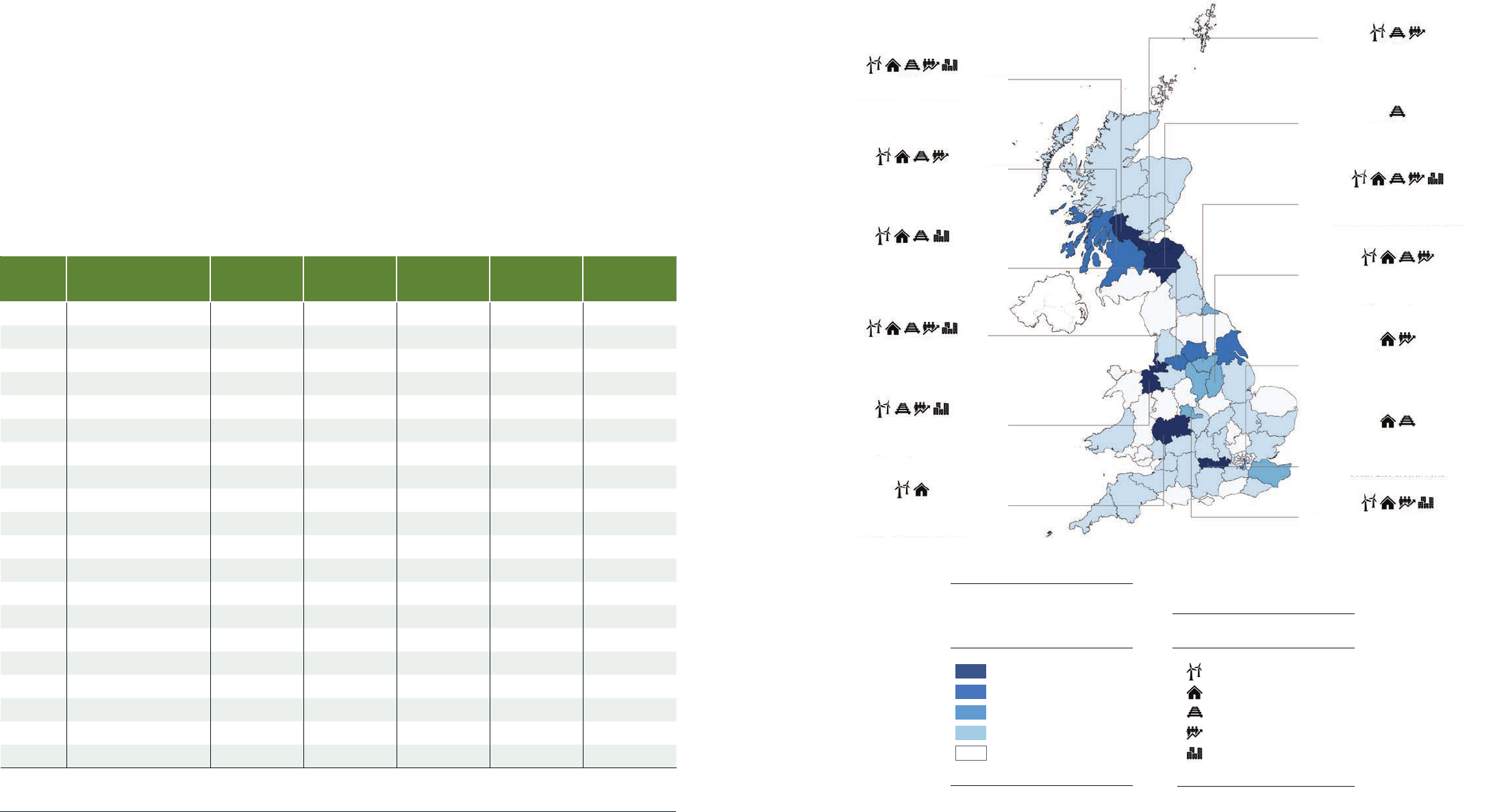

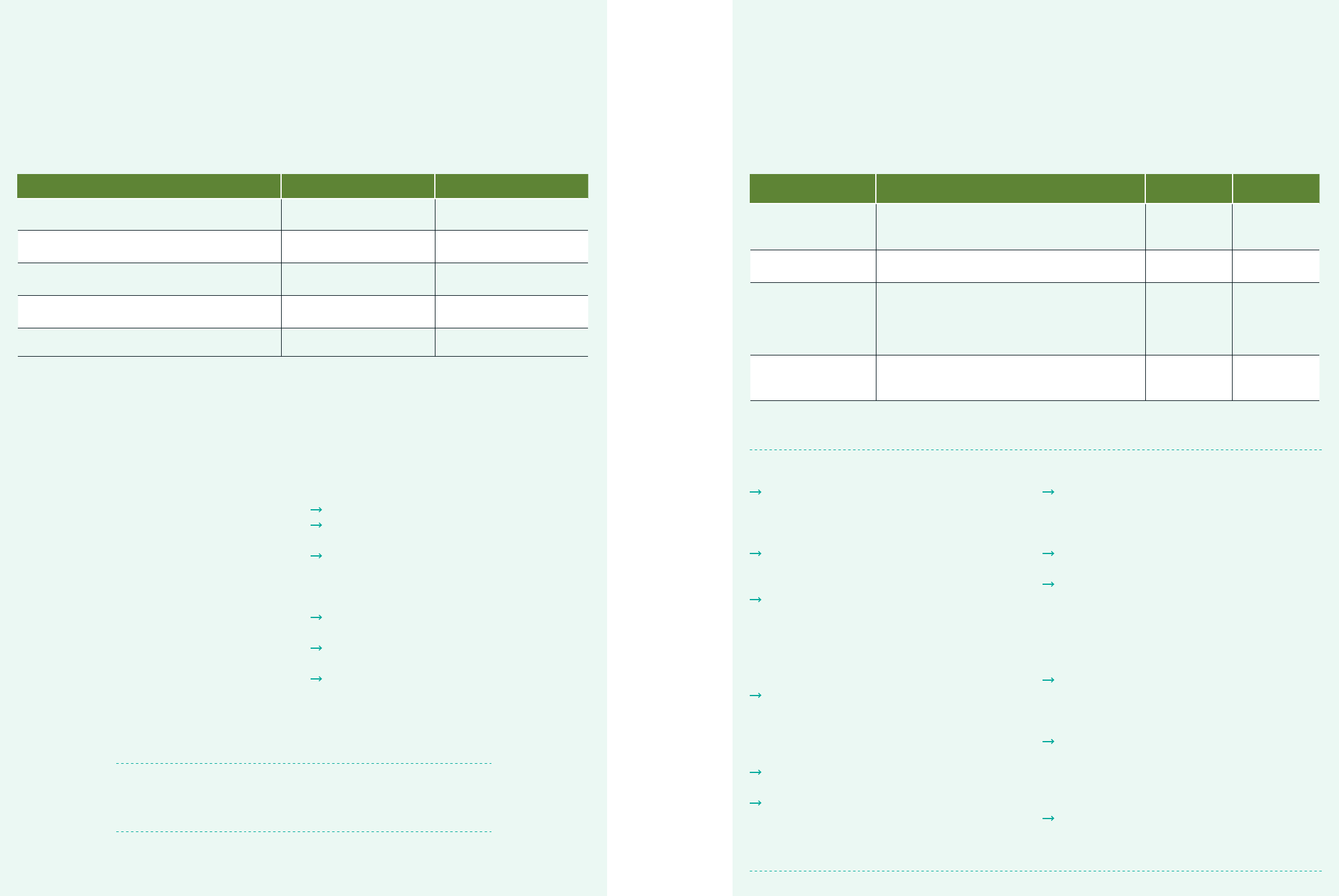

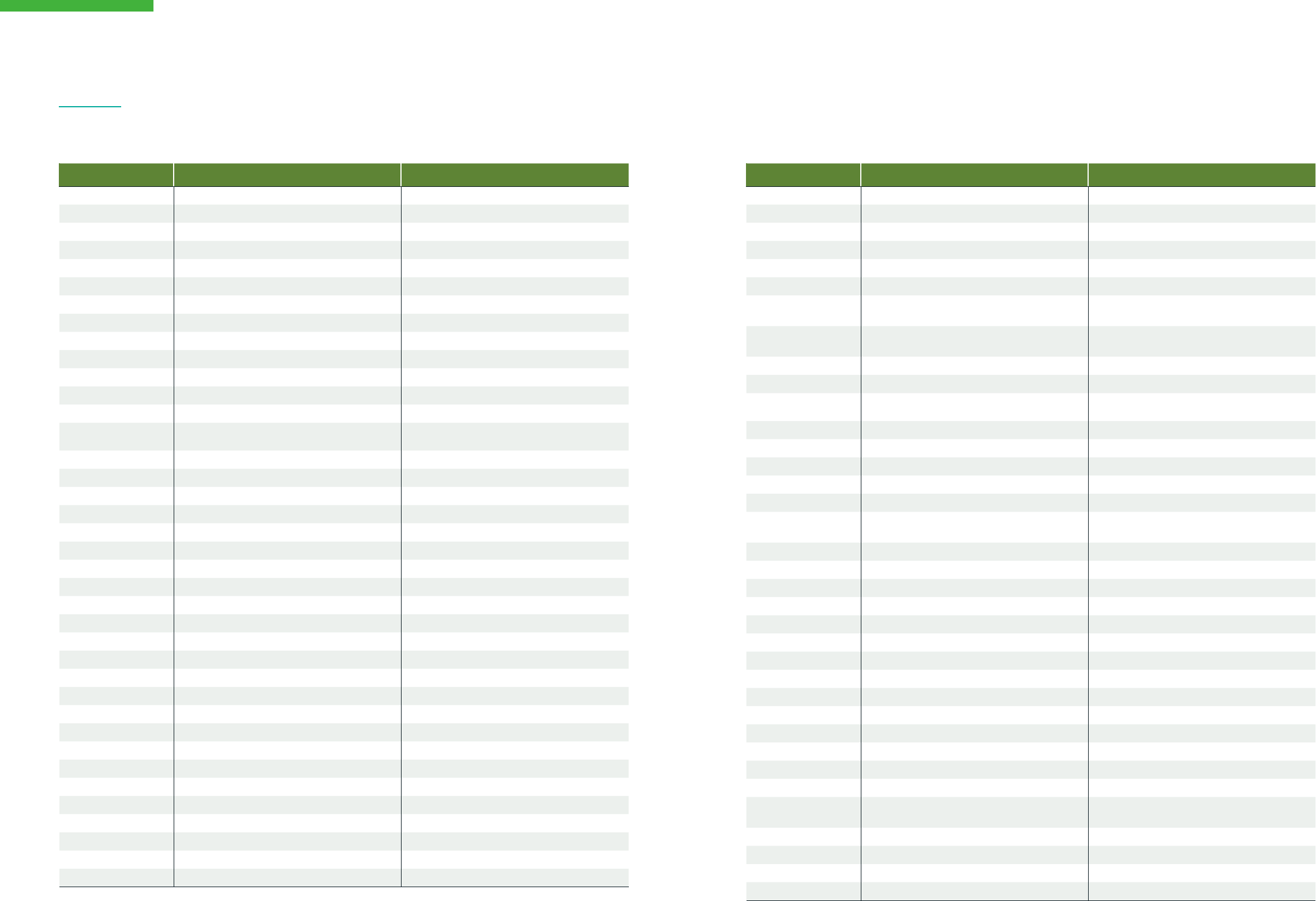

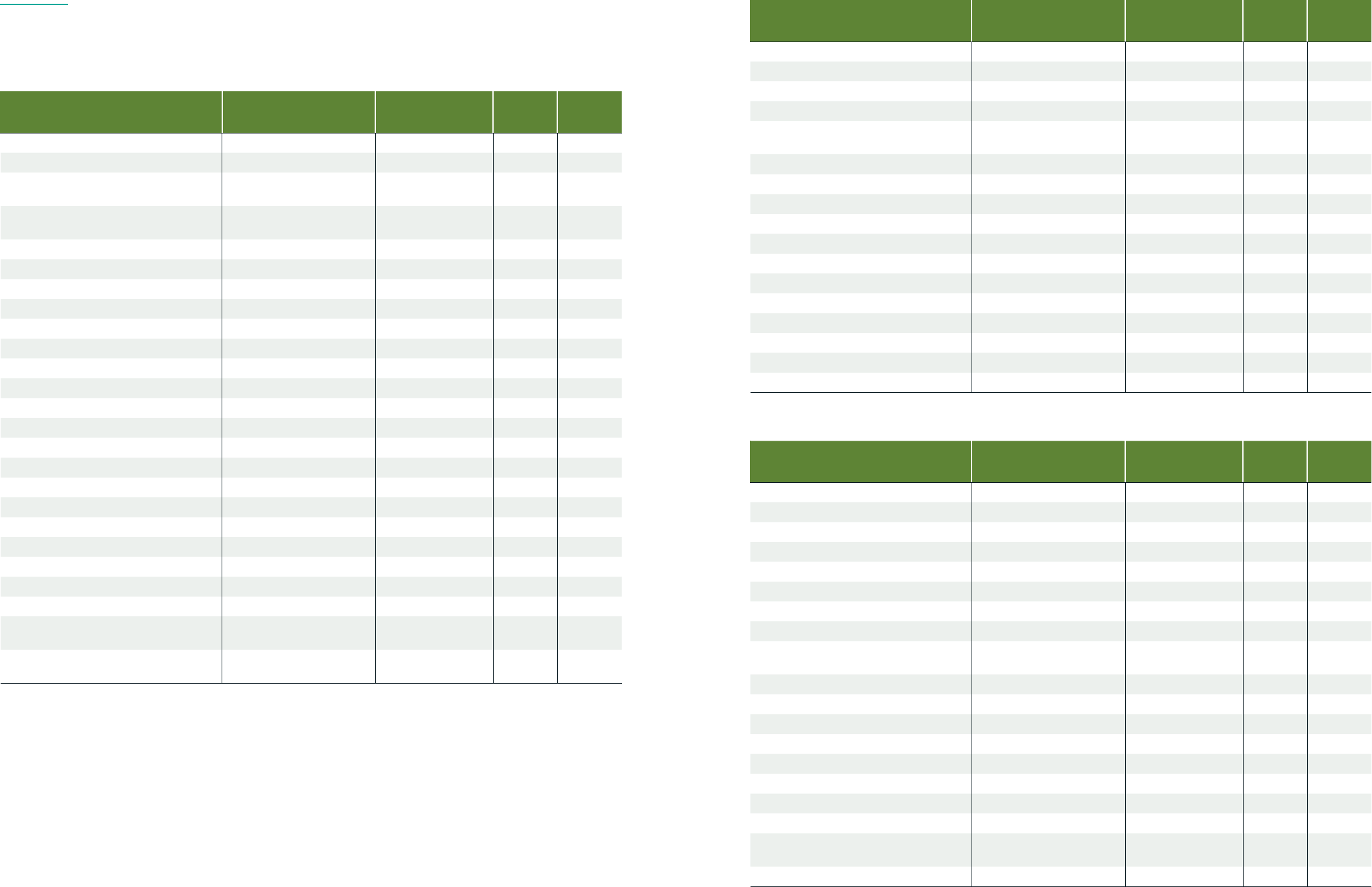

Chart 2.7 Results of financial analysis of listed funds in relevant sectors versus FTSE100

The results indicate higher returns (highlighted in green) for the time periods measured

for all eight sectors against the FTSE100, as well as a better return versus risk.

#* TIME PERIOD

MEAN RETURN % STANDARD DEVIATION % SHARPE RATIO

SECTOR FTSE SECTOR FTSE SECTOR FTSE

Clean Energy 7 Jun 13 – Sep 20

4.3 2.0

12.4

22.6 0.30 0.06

Utilities and General

Infrastructure

8 Sep 08 – Sep 20

6.9 5.1 20.0 30.5 0.31 0.14

Communications 3 Sep 08 – Sep 20

10.1 5.1 43.5 30.5 0.21 0.14

Transportation 5 Sep 08 – Sep 20

8.7 5.1

44.2

30.5 0.18 0.14

Medical Facilities 4 Sep 08 – Sep 20

6.9 5.1 23.5 30.5 0.26 0.14

Student Housing 3 Sep 13 – Sep 20

10.2 2.5 26.0 22.9 0.37 0.09

Build to Rent 3 Dec 12 – Sep 20

11.0 3.6

27.0

23.1 0.39 0.13

SME Finance and VC 36 Sep 08 – Sep 20

9.1 5.1 25.1 30.5 0.33 0.14

Source: Preqin data and Centrus analysis.*# is the number of constituent assets.

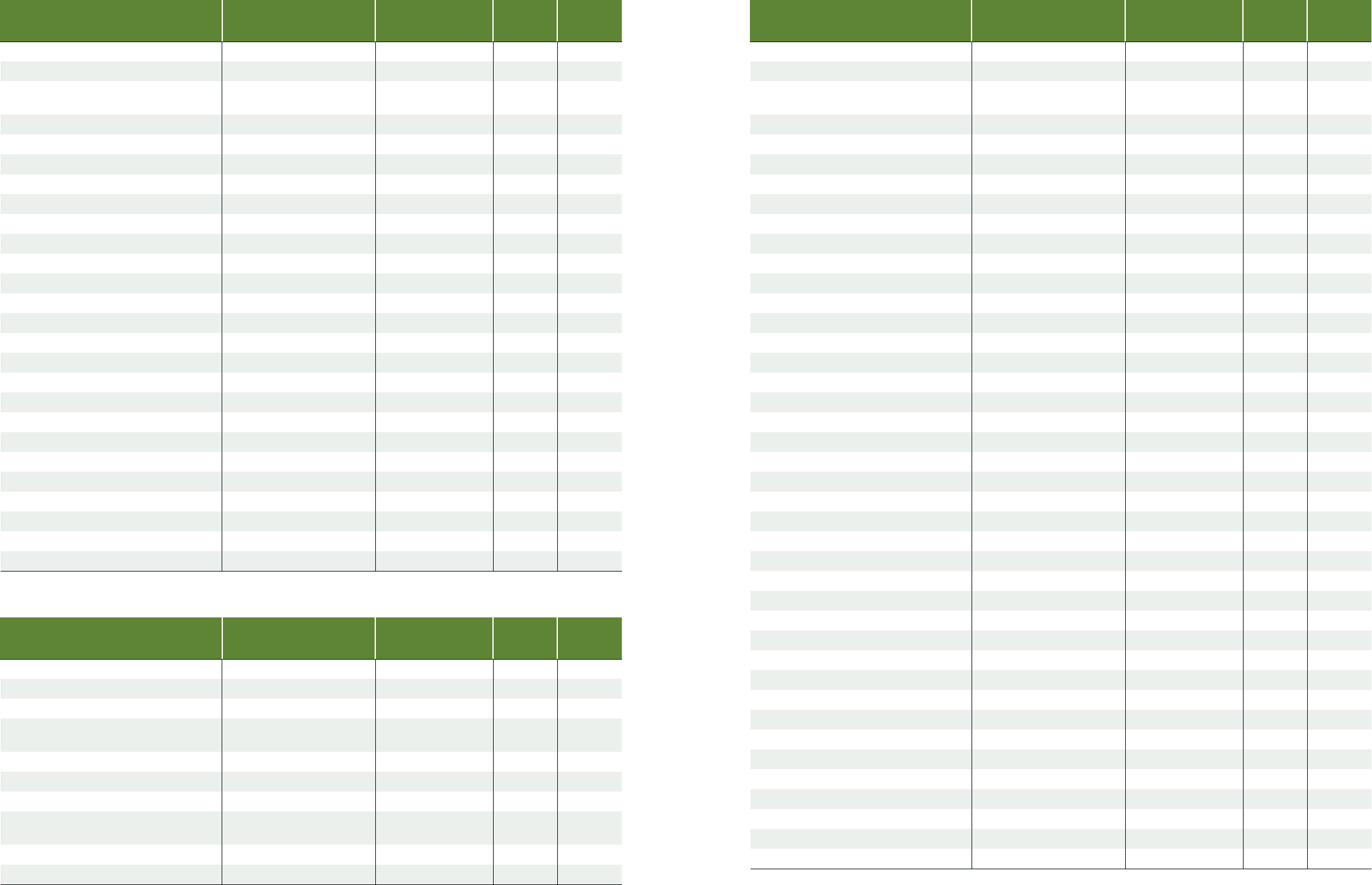

Chart 2.8 Results of financial analysis of private funds in relevant sectors

The results are consistent with their listed peers and indicate higher returns

against the FTSE 100, as well as a better Sharpe Ratio over similar timeframes.

SECTOR #* TIME PERIOD MEAN RETURN %

STANDARD

DEVIATION %

SHARPE RATIO

Utilities and General

Infrastructure

7 Mar 09 – Dec 19

7.3 26.8

0.27

Private Equity and

Venture Capital

9 Mar 11 – Sep 20

24.4 46.4 0.52

SME Debt 3 Sep 13 – Dec 19

4.1 4.4 1.00

SCALING UP INSTITUTIONAL INVESTMENT FOR PLACE-BASED IMPACT – THE WHITE PAPER 2021

0 5 10 15 20 25

17. Local Government Pension Scheme Funds: 2019-20 England & Wales (MHCLG), for Scotland and Northern Ireland individual pension fund annual reports (2019/2020).

18. Data on LGPS fund holdings was collected, quality checked and compiled by investigative journalists and research associates Edward Jones and Nicole Pihan

via the WhatDoTheyKnow website.

This section provides a baseline analysis of the current level of investment activity that is

aligned to the PBII agenda by LGPS funds. LGPS funds do already invest in the sectors

we have identified as the pillars of PBII, namely affordable housing, SME finance, clean

energy, infrastructure and regeneration. However, they have typically made these

investments based on their financial performance and not considered them through

an impact or place-based lens. Analysing the scale and nature of these existing

investments is a good place to start when considering the potential to scale up PBII.

To investigate PBII-related activity by LGPS funds we carried

out a baseline analysis using three data sources:

1

Published LGPS data were analysed to establish the

size distribution of the UK’s 98 individual LGPS funds.

17

2

Annual reports were analysed for evidence of LGPS funds

intentionally allocating capital to local and regional areas

in their investment strategies. Intentionality is a hallmark

characteristic of impact investing – we are essentially

stretching this to ‘place’.

3

Data on the underlying holdings of each LGPS fund were

analysed to identify holdings that had a UK geographical

footprint and were aligned to the PBII pillars in terms of their

asset class or sector identity. This data was sourced through

Freedom of Information requests for the financial years ending

March 2017 and 2020.

18

It is important to note that there is

no consistent reporting by LGPS funds in terms of how asset

classes are described, nor is the geography of funds regularly

reported. Hence, compiling the data set for analysis required

detailed interrogation of the nature of the individual holdings.

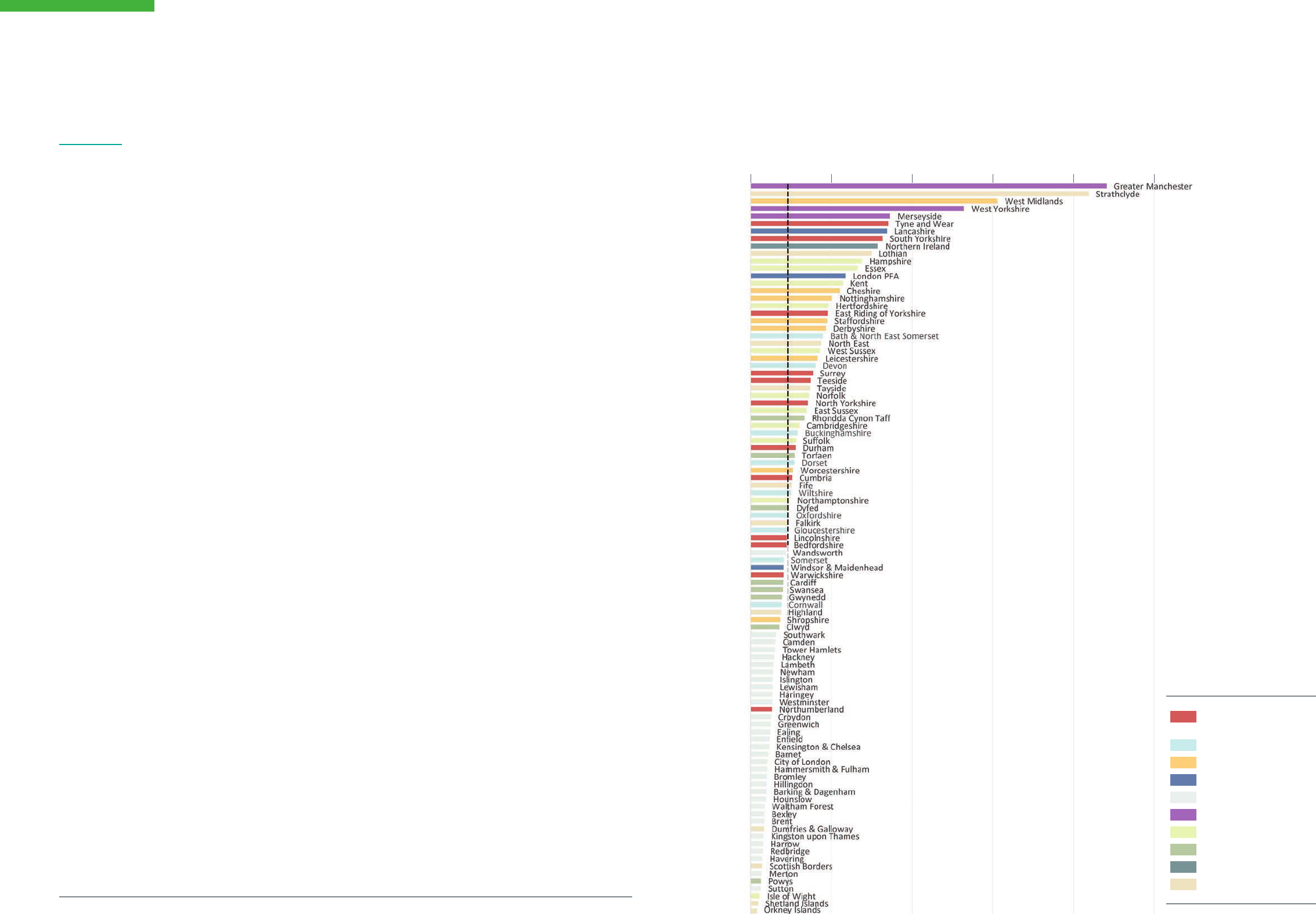

3.1 THE SIZE DISTRIBUTION

OF LGPS FUNDS

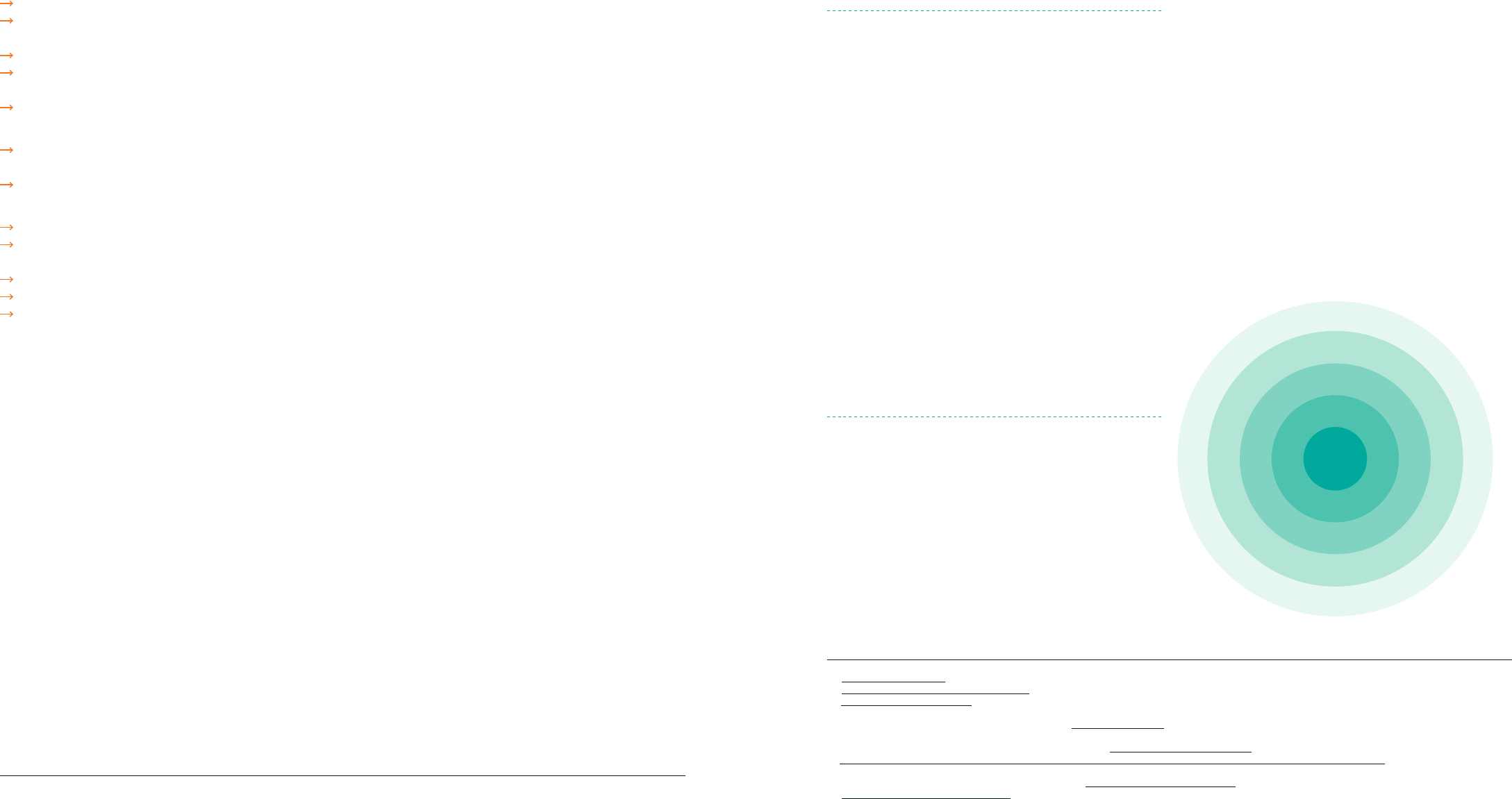

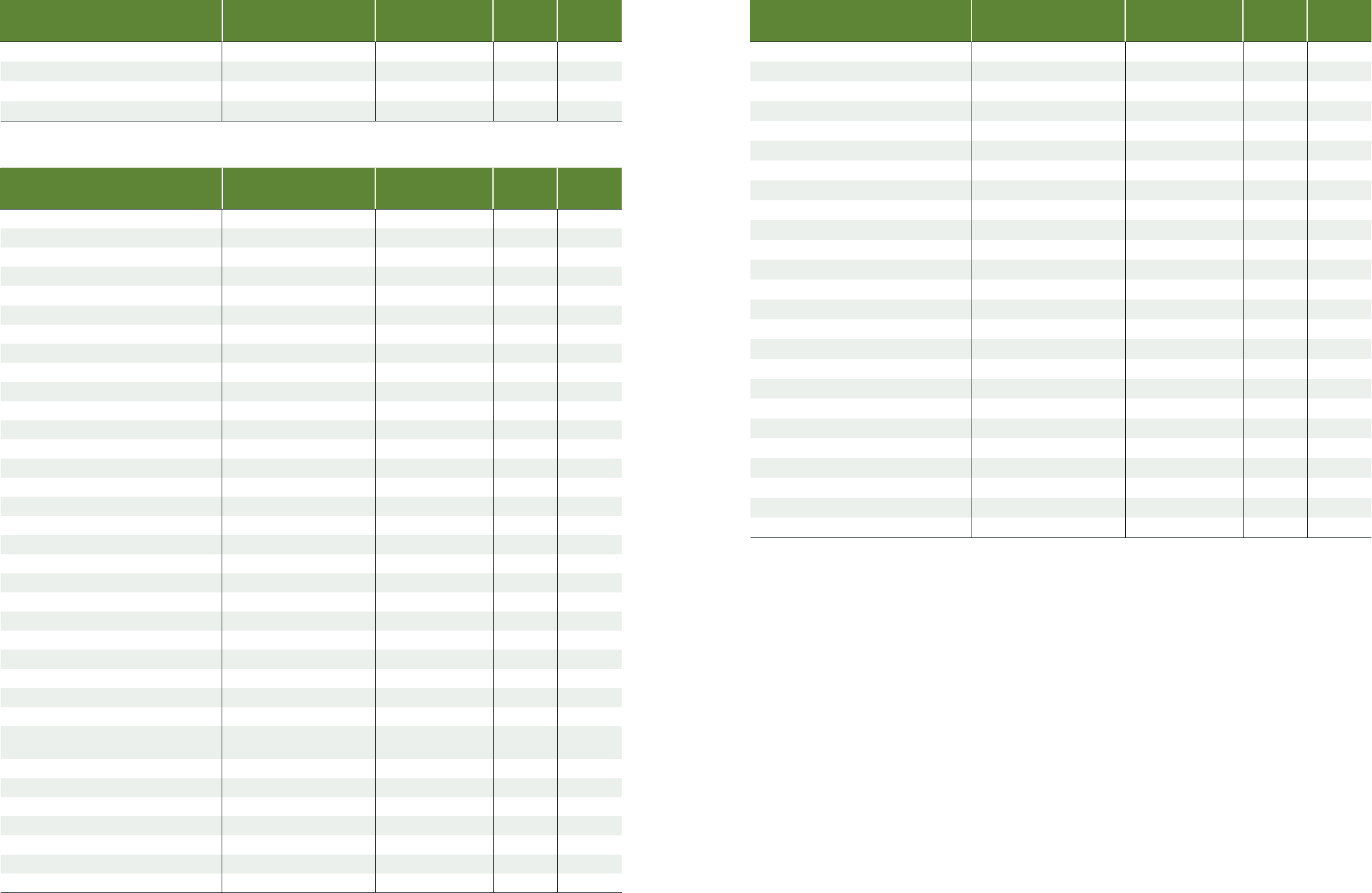

LGPS funds have a highly skewed size distribution with a few

large funds and a long tail of small funds. The median value

is £2.2 billion with the range stretching from £0.4bn (Orkney

Islands) to over £22bn (Greater Manchester). Interestingly for

the levelling up agenda, seven out of the eight largest LGPS

funds are in the North and Midlands.

This size distribution reflects the underlying organisation of

local government and is strongly correlated with population

and employment size – and most obviously, public sector

employment.

3 A BASELINE ANALYSIS OF

INVESTMENT ACTIVITY BY LGPS FUNDS

Chart 3.1 The size Distribution of the individual LGPS funds

Source: The Good Economy.

Border to Coast Pensions

Partnership

Brunel Pension Partnership

LGPS Central

Local Pensions Partnership

London CIV

Northern LGPS

The ACCESS Pool

Wales Pension Partnership

Northern Ireland LGOSC

Scotland LGPS

Median LGPS

Fund Value

LGPS Value (£bn)

SCALING UP INSTITUTIONAL INVESTMENT FOR PLACE-BASED IMPACT – THE WHITE PAPER 2021

3.2 INTENTIONALITY AND

ACTION IN LGPS FUNDS

We analysed a representative sample of 50 LGPS annual

reports for 2018/19, including the 10 largest funds with the

remaining 40 differing in size and covering all home nations,

regions of England and asset pools. We carried out an in-

depth review of the funds’ annual reports, particularly their

investment strategy statements and portfolio allocations, for

evidence of:

Intentionality – evidence of a clear intention to invest in

the UK at the national, regional or local levels, including

the LGPS funds’ own geographic areas and within the key

sectors defined in our PBII pillars i.e. housing, SME finance,

clean energy, infrastructure and regeneration.

Action – evidence of investment in key PBII sectors

in the UK.

INTENTIONALITY

Only six out of the 50 LGPS funds reviewed (12%) demonstrate

a clear intentionality to make place-based investments as

stated in their annual reports. These six LGPS funds were:

Cambridgeshire, Clwyd, Greater Manchester, Strathclyde,

Tyne and Wear and West Midlands.

‘Place’ and ‘local’ have different meanings across these

pension funds. In some cases, ‘place’ is clearly defined as

the local catchment area for the pension fund concerned

(e.g. Cambridgeshire) or the region (e.g. West Midlands). For

others, ‘local’ can mean a UK nation. Clwyd Pension Fund,

for example, is interested in investing in Wales. Notably,

Clwyd is also the only fund to have any stated intent to direct

investment to deprived areas. The six LGPS funds spotlighted

for their place intentionality also reported making investments

in the five key sectors.

Of these six, only Greater Manchester has an approved

capital allocation to invest up to 5% of its total assets locally.

Examples of the investment strategy statements that we

interpreted as an intentional commitment to place-based

investing can be found at the bottom of this and the following

page.

A further 19 pension funds reported investing in these sectors

without any place-based intentionality. The overall results

of this analysis indicate the low base of observable LGPS

interest in place-based investing that currently exists.

We continue to engage in local investment opportunities and building

local talent, noting in particular, property and housing investment

within the West Midlands region and the pool of strong candidates who