Direct Primary Care (DPC):

Potential Impact on Cost, Quality, Health Outcomes,

and Provider Workforce Capacity

A Review of Existing Experience & Questions for Evaluation

Health Policy Programs Group

UW Health Policy Group 1 | 20

Table of Contents

I. Federal Law and DPCs.............................................................................................................. 2

II. State DPC Laws ........................................................................................................................ 3

III. Evaluations and Case Studies .................................................................................................. 7

IV. The Value Proposition for Purchasers and Consumers ........................................................... 8

A. Preventive Services Covered by Health Plans ........................................................................... 8

B. Value-Added Calculation for Consumers ................................................................................. 11

V. Health System Value: Utilization, Quality, Outcomes .......................................................... 14

A. Volume of Care and Utilization .................................................................................................. 14

B. Quality and Outcomes ................................................................................................................ 11

VI. How do DPCs Affect the Primary Care Workforce? ............................................................. 16

VII. Conclusion: Questions for Consideration ............................................................................ 19

VIII. Other Background Reading .................................................................................................. 20

UW Health Policy Group 2 | 20

Direct Primary Care (DPC) contracts, or “medical retainer agreements,” are a healthcare delivery model

where a provider offers unlimited specified routine health care services for a monthly fee.

1,2

Proponents

of DPC suggest that the delivery method will improve access to care, reduce administrative costs, foster

stronger patient-provider relationships, and reduce reliance on expensive emergency department

services. Critics of DPC contend that it double-charges for services already covered by insurance, and

that DPC contracts lack accountability for quality and access. This paper 1) describes proposed and

existing DPC bills, 2) reviews existing DPC experience and evaluations, and 3) considers what effect DPC

could have on health care in Wisconsin.

I. Federal Law and DPCs

Federal law concerning DPC arrangements falls into two main categories: DPC and the private insurance

market, and DPC and the Medicaid program.

DPC and the Private Insurance Market

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) allows a qualified health plan (QHP) issuer to

“provide coverage through a direct primary care medical home…so long as the QHP meets all

requirements that are otherwise applicable and the services covered by the direct primary care medical

home are coordinated with the QHP issuer.” That is, DPC may be included in plans sold on the ACA

insurance exchanges, but must be paired with a wraparound insurance policy covering everything

outside of primary care.

3

In April 2018, the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) released a public request

for information regarding DPC models for primary care and other specialties, titled “Direct Provider

Contracting.” That document is available here:

https://innovation.cms.gov/ini…/direct-provider-

contracting/. CMS solicited input on direct provider contracting between payers and primary care or

multi-specialty groups. This would inform potential testing of a DPC model within the Medicare fee-for-

service program (Medicare Parts A and B), Medicare Advantage program (Medicare Part C), and

Medicaid.

Current Internal Revenue Service (IRS) rules prohibit individuals with health savings accounts (HSAs)

paired with high deductible health plans (HDHPs) from having an agreement with a DPC provider. The

IRS interprets DPC arrangements as health plans under Section 223(c) of the Internal Revenue Code, The

law is unclear whether primary care services are qualified health expenses under Section 213(d) of the

1

Wisconsin Legislative Council, Amendment Memo, 2017 Senate Bill 670, Senate Substitute Amendment 1.

February 2, 2018. https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/2017/related/lcamendmemo/sb670.pdf

2

Chappell GE. 2017. Health Care’s Other “Big Deal”: Direct Primary Care Regulation In Contemporary American

Health Law. Duke Law Journal. Vol. 66: 1330-1370.

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4774/9abed07d68ebbb7006599b15c568e62350c2.pdf

3

45 C.F.R. § 156.245; Dave Chase, Direct Primary Care: Regulatory Trends, FORBES (July 10, 2013),

http://www.forbes.com/sites/davechase/2013/07/10/direct-primary-care-regulatory-trends/

UW Health Policy Group 3 | 20

code if paid for as a capitated periodic fee rather than on a fee for service basis. IRS regulations require

HSAs be paired with an HDHP, and the HSA holder may not have a second health plan. The IRS

interpretation of DPC as a health plan bars an individual who has an agreement with a DPC provider

from funding an HSA.

A bipartisan bill in Congress, the Primary Care Enhancement Act (HR 365/S. 1358), clarifies the tax code

regarding the use of HSAs for DPC. The bill would clarify the tax code to allow patients with HSAs paired

with HDHPs to use those funds to pay for periodic fee-based DPC. As of June 2018, the House

Committee on Ways and Means has not yet considered this bill.

DPC and Medicaid

Federal Medicaid law specifies that that “The State Medicaid agency must require all ordering or

referring physicians or other professionals providing services under the State plan or under a waiver of

the plan in the fee-for-service program to be enrolled as participating Medicaid providers.”

4

A DPC

provider would need to be a Medicaid participating provider to serve Medicaid members. However,

CMS has determined that, in Medicaid risk-based managed care arrangements, states hold discretion

over provider enrollment requirements for the ordering or referring physicians.

5

An advocacy website

of a group that supports expansion of DPC contracts reviews questions that DPC practices have about

this CMS guidance.

6

II. State DPC Laws

Twenty-five states have passed legislation generally defining DPC outside of state insurance regulation.

7

This state action defines DPC as a medical service, not a health plan. Wisconsin, Georgia, Maryland,

Pennsylvania and South Carolina have introduced DPC legislation, but have not enacted those bills into

law. Montana Governor Steve Bullock is the only governor to have vetoed a DPC bill, doing so in 2017.

Discussion of the origin, history, and legislative framework for each state’s DPC bill are available from

other sources, with detailed tables as of 2017.

8,9

About half of enacted laws use the phrase “direct

primary care” while the other half use the substantively equivalent phrase “medical retainer

agreement.” All bills include language expressly stating that DPC is not insurance, and that DPC is not

4

42 CFR § 455.410(b)

5

CMS, DHHS. Cindy Mann, Director. Medicaid/CHIP Provider Screening and Enrollment. December 23, 2011.

https://www.medicaid.gov/Federal-Policy-Guidance/downloads/CIB-12-23-11.pdf

6

DPC Frontier. Medicaid – A Full Analysis. https://www.dpcfrontier.com/medicaid/

7

Details on these bills are available at https://www.dpcare.org/state-level-progress-and-issues.

8

Eskew P. Direct Primary Care Business of Insurance and State Law Considerations. Unpublished Paper.

https://static1.squarespace.com/static/54c15fbce4b06765d7d750d5/t/59cc42388fd4d26e72d28126/1506

558521439/Direct+Primary+Care+Business+of+Insurance+and+State+Law+ConsiderationsNYSBA.pdf

9

Appendix to Health Care’s Other “Big Deal”: Direct Primary Care Regulation in Contemporary American Health

Law Glenn E. Chappell 66 DUKE L.J. (March 2017)

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4774/9abed07d68ebbb7006599b15c568e62350c2.pdf

UW Health Policy Group 4 | 20

subject to regulation by the state’s Insurance Commissioner or other state insurance regulators. Each of

these laws defines DPC similarly, as an agreement between a primary care provider and a patient to

provide unlimited access to primary care services in exchange for an agreed-upon monthly fee for an

agreed-upon period. Various state laws address other elements. Alabama, for example, expressly

includes dentists as providers covered under the bill. The Direct Primary Care Coalition, a group that

advocates for expansion of DPC, has drafted model DPC legislation.

10

In theory, DPC paired with a wrap-around health plan, may be offered in ACA exchanges, by self-insured

employers, unions, and by Medicare Advantage and Medicaid managed care organizations. State laws

vary in whether they allow DPCs to engage in third-party billing, or the ability of DPC providers to

receive reimbursement from private insurers or state Medicaid agencies:

• Only Washington and Louisiana allow insurer reimbursement for member DPC subscriptions.

• Michigan,

11

Nebraska,

12

Louisiana,

13

and West Virginia

14

have statutory language that permit

Medicaid payments for DPCs, while Mississippi and Texas preclude DPCs from billing Medicaid.

15

• Missouri, Arkansas, and Oklahoma do not prohibit DPCs from billing insurers for services.

Missouri’s law expressly allows payments from health savings accounts, flexible spending

arrangements, or health reimbursement arrangements.

State Pilot Programs

In 2006, West Virginia enacted the Preventive and Primary Care Pilot Program to provide such services

to the uninsured for a prepaid fee (West Virginia Code § 16-2J.)

16

The law specified that health care

providers in this program were not providing insurance or offering insurance services. A DPC advocate

reviewed the West Virginia program and how various elements, such as limiting its scope to the

uninsured population, might restrict the success of DPC practices.

17

That writer compared the West

Virginia provisions to a DPC law passed in 2007 by State of Washington, and concluded that

Washington’s legislation, along with elements of other states’ laws, better promotes successful DPC

practice:

States considering passing similar legislation should consider enacting a hybrid of the West

Virginia, Washington, Utah, and Oregon statutes, taking the most helpful portions from each.

Physicians should be able to market their services directly to patients or employers without

regard to the current insurance status. Avoiding unneeded scope of service restrictions will

10

https://www.dpcare.org/dpcc-model-legislation

11

Michigan Public Act 158 of 2017

12

Nebraska Neb. Rev.St. § 71-9510.

13

La. Stat. § 37:1360.85.

14

W. Va. Code. § 30-3F-2.

15

Miss. Code Ann. § 83-81-3(c) (2015); Tex. Occ. Code § 162.254 (2015).

16

West Virginia Health Care Authority. Primary Care Pilot Program.

https://hca.wv.gov/primarycare/Pages/default.aspx

17

Eskew P. Direct Primary Care Membership Medicine. West Virginia Medical Journal. March/April 2014 Vol. 110:

8-11. http://cdn.coverstand.com/30875/197958/83364ec4719c32123930be5019940709e1e49d59.5.pdf

UW Health Policy Group 5 | 20

magnify the economic benefits experienced by patients of the DPCMM practices. Rules regarding

the acceptance of new patients and discontinuing care are helpful, and the Washington

legislation provides an excellent example in this regard.

West Virginia renewed its pilot program through 2016, then adopted a new statutory provision for

Direct Primary Care Practice in 2017. The new law allows that, while a provider may not bill third parties

for services rendered under the DPC agreement, “[a] primary care provider may accept payment for

medical services or medical products provided to a Medicaid or Medicare beneficiary” and

“[a] patient or legal representative does not forfeit insurance benefits, Medicaid benefits or Medicare

benefits by purchasing medical services or medical products outside the system.”

18

Michigan’s legislature, in 2017, directed its Medicaid agency to apply to CMS for a waiver to allow DPC

for Medicaid enrollees.

19

The legislature appropriated funds for a one-year DPC pilot program, to

include no more than 400 enrollees across various Medicaid eligibility categories. Michigan has not yet

implemented the pilot program, and the Michigan Medicaid agency reports that the timeframe depends

on negotiations between the Medicaid health plans and any potential contracted providers.

The State of Nebraska codified DPC in state law, with the Governor signing 2015 NE L.B. 817 into law in

March 2016. With DPC available on the commercial market, Nebraska’s legislature introduced NE L.B.

1119,

20

which the Governor signed in April 2018 as the Direct Primary Care Pilot Program Act. The

program begins in fiscal year 2019-2020 and runs through fiscal year 2021-2022. This law requires the

State Health Insurance Program to include two direct primary care coverage options for participating

state employees.

21

Wisconsin DPC Bills: 2017 AB 798 and SB 670

Wisconsin’s 2017 Assembly Bill 798 (AB 798) was introduced in December 2017, along with companion

Senate Bill 670 (SB 670).

22

The Senate Committee on Public Benefits, and the Assembly Committee on

Small Business Development passed identical substitute amendments to SB 670 and AB 798,

respectively, in February 2018.

23

The full Assembly passed AB 798, as amended, but the Senate did not

take up the bill before the end of the legislative session, and the proposal was not enacted into law.

18

W. Va. Code § 30-3F-2. See also: West Virginia Board of Medicine, Direct Primary Care Practice.

https://wvbom.wv.gov/Direct_Primary_Care_Practice.asp#30-3F-2

19

Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. Implementation of the Direct Primary Care Pilot Program,

Quarterly Report 1. January 19, 2018.

https://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdhhs/Section_14078_PA_158_of_2017_Quarterly_Rpt_1_6148

60_7.pdf

20

https://nebraskalegislature.gov/bills/view_bill.php?DocumentID=34744

21

Office of Governor Pete Ricketts, State of Nebraska. Gov. Ricketts Signs Legislation Expanding Healthcare

Options. April 13, 2018.

https://governor.nebraska.gov/press/gov-ricketts-signs-legislation-expanding-

healthcare-options

22

https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/2017/proposals/sb670

23

https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/2017/related/amendments/sb670/ssa1_sb670

UW Health Policy Group 6 | 20

The original bill would have specified that DPC does not fall under regulation as an insurance plan, and

required that the Wisconsin Department of Health Services (DHS) establish and implement a DPC

program for Medicaid enrollees. The Legislative Reference Bureau summarizes SB 670 as follows:

The bill allows a health care provider and an individual patient or employer to enter into a direct

primary care agreement and requires the Department of Health Services to establish and

implement a direct primary care program for Medical Assistance recipients. A direct primary care

agreement is a contract in which the health care provider agrees to provide routine health

services such as screening, assessment, diagnosis, and treatment for the purpose of promotion of

health or the detection and management of disease or injury, dispensing of medical supplies and

prescription drugs, and certain laboratory services for a specified fee over a specified duration. A

valid direct primary care agreement outside of the Medical Assistance program must, among

other things, state that the agreement is not health insurance and that the agreement alone

may not satisfy individual or employer insurance coverage requirements under federal law. The

bill exempts direct primary care agreements from the application of insurance law. The bill also

allows DHS to investigate complaints related to private direct primary care agreements.

Services. The bill defines “routine health care service” to mean screening, assessment, diagnosis,

and treatment for the purpose of promotion of health or the detection and treatment for the

purpose of promotion of health or the detection and management of disease or injury. The substitute

amendment removed the bill’s specific provisions on laboratory services and dispensing of medical

supplies and prescription drugs.

Medicaid Pilot Program

The Wisconsin Legislative Council summarizes the provisions of the bill and substitute amendment as

follows:

The bill requires the Department of Health Services (DHS) to contract with one or more primary

care providers to implement a direct primary care program for MA recipients. DHS must

enter participants into a direct primary care agreement to receive routine health services from

one of these providers for a monthly fee, as will be specified in the agreement. After the program

is implemented, DHS must submit annual reports to the Legislature.

The substitute amendment removes these provisions and instead requires DHS to convene a

work group to propose a direct primary care pilot program. A hearing must be held on the

proposal, and legislation must be introduced following the hearing. The work group is also

directed to submit a report regarding implementation of an “alternative payment model” for

potentially preventable hospital readmissions of MA recipients.

The bill text, prior to removal by substitute amendment, contemplates how the Medicaid pilot might

operate, specifically noting an average fee of $70 per month.

UW Health Policy Group 7 | 20

III. Evaluations and Case Studies

This existing scholarly literature on DPCs provides descriptive and survey information,

24

but generally

lacks rigorous studies on cost, quality, and outcomes.

25

One study assessed the effect of the personalized health care model used by MD-Value in Prevention

(MDVIP), a collective direct primary care group with practices in 43 states and the District of

Columbia).

26

This study reported substantial savings per patient, mostly because of reductions in

hospital utilization. But the study did not adjust for baseline health or socioeconomic factors of its

members relative to comparison population – factors that would affect health care use. This study,

therefore, does not allow conclusion about the impact of the delivery model.

The Qliance Medical Group has received perhaps the most attention in the literature. Founded in 2007

in Seattle, Qliance established itself as the nation’s largest DPC healthcare consortia. Supported by

Washington State’s permissive DPC law, Qliance served individuals, employers, and Medicaid

members.

27

In 2014, the company became the nation’s first DPC provider to join the ACA health

insurance exchange. By 2015, Qliance groups served 35,000 patients in the Seattle area, half of whom

Medicaid covered.

28

Qliance had early success with market expansion, but faltered financially and, by 2017, had closed all

clinic operations.

29

The Qliance Medical Group filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy on May 7, 2018.

30

The

payment levels apparently proved insufficient to cover the DPC costs. Others have voiced this concern:

One 2015 review of existing DPC practices reported that DPCs charged patients an average $77.38 per

month,

31

while another reported monthly rates between $42 and $125.

32

Such rates fall substantially

24

https://www.dpcfrontier.com/academic-articles

25

Cole E. Direct Primary Care: Applying Theory to Potential Changes in Delivery and Outcomes. J Am Board Fam

Med July-August 2018; 31:605-611

26

Klemes A, Seligmann RE, Allen L, Kubica MA. Warth K Kaminetsky B Personalized preventive care leads to

significant reductions in hospital utilization. Am J Manag Care., 2012, vol. 18:e453-60.

27

Qliance and Healthcare Reform Fact Sheet for Individuals

http://qliance.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/Qliance-and-Healthcare-Reform-Fact-Sheet_Final.pdf

28

von Drehle D. Medicine Is About to Get Personal, TIME, Dec. 22, 2014. http://time.com/3643841/medicine-

gets-personal

29

Andrews M. A Pioneer In 'Flat-Fee Primary Care' Had To Close Its Clinics. What Went Wrong? NPR Shots. June 20,

2017.

https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2017/06/20/533562142/a-pioneer-in-flat-fee-primary-

care-had-to-close-its-clinics-what-went-wrong

30

Ellison A. Direct primary care group files for bankruptcy after abruptly closing clinics. Becker’s Hospital Review.

May 30, 2018.

https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/finance/direct-primary-care-group-files-for-

bankruptcy-after-abruptly-closing-clinics.html

31

Eskew P, Klink K. Direct Primary Care: Practice Distribution and Cost Across the Nation. JABFM, Journal of the

American Board of Family Medicine. November–December 2015 Vol. 28 No. 6.

http://www.jabfm.org/content/28/6/793

32

Rowe K, Rowe W, Umbehr J, Dong F, Ablah E. Direct Primary Care in 2015: A Survey with Selected Comparisons

to 2005 Survey Data. Kansas Journal of Medicine. 2017;10(1):3-6.

UW Health Policy Group 8 | 20

short of the average of $182.76 per month charged by "concierge" or "boutique" medical practices,

which also usually bill insurers for their services.

The literature includes descriptive reports of Qliance early operations,

33

but offers no independent

evaluations of Qliance performance. Qliance, in a 2015 press release, announced that its model “delivers

20% lower overall healthcare costs, increases patient satisfaction, and delivers better care.”

34

Qliance

attributed these savings to a substantial reduction in ER visits, inpatient days, specialist visits, advanced

radiology visits, along with more primary care visits.

However, external evaluators did not conduct the Qliance study. The study was not subject to peer

review, and was not published in a scientific journal. It does not specify whether the underlying risk

status differed between those who joined Qliance relative to a comparison group, how long the Qliance

members had been with Qliance, or whether the Qliance members might have visited any providers

outside of their Qliance contract that went unrecorded in the study. For these reasons, the Qliance’s

reported results may not be attributable to the DPC as a delivery model. DPC may attract a lower risk

member population, and some observers suggest that unlimited primary care encourages the "worried

well" to get more care than they need, but does not necessarily promote evidence-based services that

improve health.

IV. The Value Proposition for Purchasers and Consumers

DPC offers a potential value proposition in two regards: potential savings in health care costs, and

improved patient experience and satisfaction. DPC proponents point to potential benefits for the health

care system, through a reduction in overall health insurance premiums or health care payments if the

DPC can avert unnecessary referral, specialty, hospital, imaging, laboratory, prescription drug costs and

other services. DPC’s value proposition to consumer: expansive access to a primary care provider and all

services provided within that provider’s practice, and longer visit times with their health care provider,

potentially improving the health care experience.

Ultimately, the value to both purchaser and consumer depends on whether the model reduces financial

outlays and improves health outcomes. This section looks at the DPC interaction with other insurance

benefits and the potential to deliver cost savings to the consumer.

A. Preventive Services Covered by Health Plans

A low-risk consumer could likely get many, if not most, needs met through their primary care provider.

That consumer would then need to get a wrap-around plan with a high deductible and co-payments in

the event of a hospitalization or need for specialist services. However, with the ACA’s preventive

services requirement, that plan will already provide coverage for most of the screening and preventive

33

Wu WN, Bliss G, Bliss EB, Green LA. Practice profile. A direct primary care medical home: the Qliance experience.

Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(5):959–962.

34

Qliance. New Primary Care Model Delivers 20 Percent Lower Overall Healthcare Costs, Increases Patient

Satisfaction and Delivers Better Care. January 15, 2015.

https://www.prnewswire.com/news-

releases/new-primary-care-model-delivers-20-percent-lower-overall-healthcare-costs-increases-patient-

satisfaction-and-delivers-better-care-300021116.html

UW Health Policy Group 9 | 20

services that the DPC would also provide. The question here becomes whether the DPC subscription fee

adds value beyond the preventive services already built into any other coverage that includes mandated

preventive services.

The ACA requires that private insurance plans cover recommended preventive services without any

patient cost-sharing.

35

This means that consumers paying for both insurance and DPC will be paying

twice for those services, unless the insurance plan can carve out the required preventive service benefit

and use the DPC provider to fulfill the requirement.

In 2013, the IRS confirmed that high-deductible health plans (HDHPs) also must cover all preventive

services mandated under the ACA without imposing a deductible.

36

Private health plans must cover a

range of preventive services and may not impose cost-sharing (such as copayments, deductibles, or co-

insurance) on patients receiving these services. These requirements apply to all private plans – including

individual, small group, large group, and self-insured, except plans that maintain “grandfathered” status.

To have been classified as “grandfathered,” plans must have existed prior to March 23, 2010, and

cannot make significant changes to their coverage (for example, increasing patient cost-sharing, cutting

benefits, or reducing employer contributions).

The clinical preventive services fall into four categories

37

: 1) Evidence-Based Screenings and Counseling,

2) Routine immunizations, 3) Preventive Services for Children and Youth, and 4) Preventive Services for

Women.

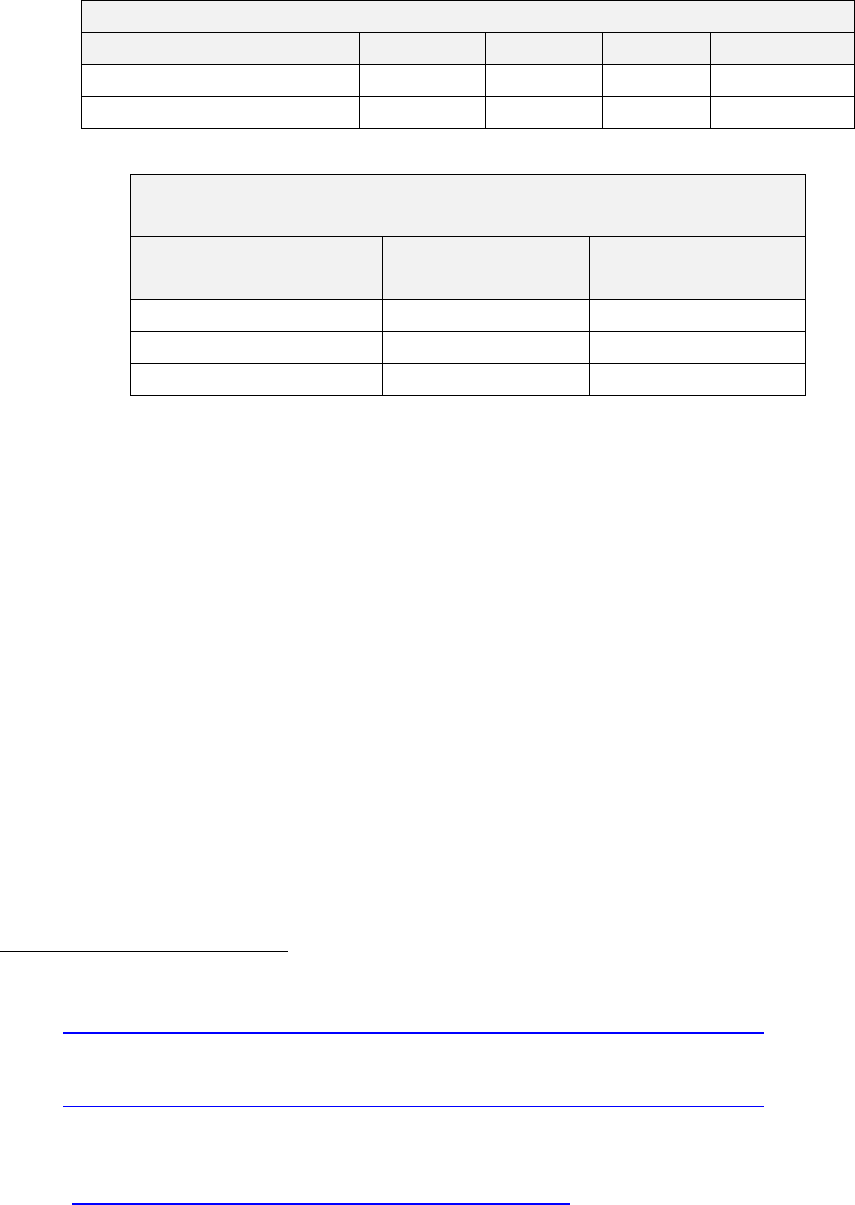

Table 1 compares the coverage that consumers might have for services under a DPC agreement, as

defined by SB 670, relative to what they would have under standard health plan. A consumer within a

DPC agreement would presumably also purchase a complimentary “wrap-around” health plan to cover

the services not provided within by the DPC contract, including most prescription drugs, laboratory,

specialist, and hospitalization services. The degree to which a consumer would use such coverage would

will depend on risk profile and the consumer’s pre-existing health conditions.

35

Healthcare.gov. Preventive health services. https://www.healthcare.gov/coverage/preventive-care-benefits/

See also: Preventive Services Covered under the Affordable Care Act. Quartz.

https://unityhealth.com/docs/default-source/docs/acapreventiveservices.pdf?sfvrsn=2

36

IRS Notice 2013-57. https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-13-57.pdf

37

For detail, see https://www.kff.org/health-reform/fact-sheet/preventive-services-covered-by-private-health-

plans/#endnote_link_160040-3

UW Health Policy Group 10 | 20

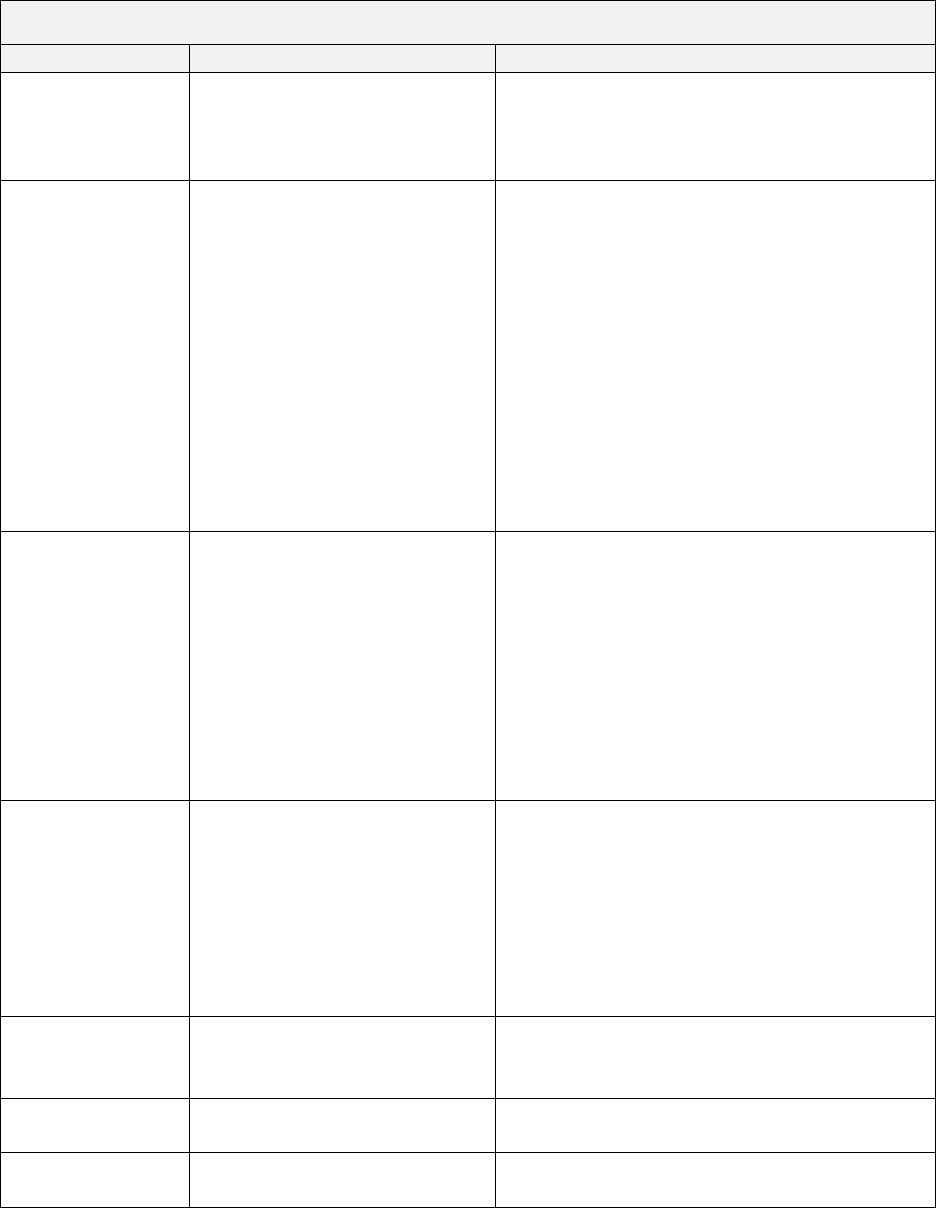

Table 1. Services Covered under DPC Contract and under Standard Health Plan Coverage

Services

Direct Primary Care

Standard Health Plan Coverage

Screening

No additional cost to consumer

for screening services that fall

within the scope of the DPC’s

ability and scope.

No out-of-pocket cost to the consumer; most

screening services will fall within the ACA’s

preventive services mandate and therefore

would be covered.

Assessment,

Diagnosis, and

Treatment

No additional cost to consumer

for assessment, diagnosis, and

treatment services that fall

within the scope of the DPC’s

ability and scope.

Consumer remains exposed to

full cost for assessment,

diagnosis, and treatment

services by other providers

beyond the DPC, including

referrals, specialists, and

second opinions.

No out-of-pocket cost to consumer for some

assessment, diagnosis, and treatment that

occur incidental to the preventive services.

For example, removal of polyps during a

routine colonoscopy would be included as a

“free preventive service.”

Other office visits, assessment, diagnosis, and

treatment services would be covered, often

pre-deductive and subject to a co-payment.

Dispensing of

Medical Supplies

and Prescription

Drugs

Limited only to product

dispensed directly within the

clinic by the DPC provider.

Consumer remains fully

exposed to most prescription

drug costs, as those are

generally dispensed by a

licensed pharmacy outside of

the primary care office setting.

Covered, subject to health plan’s cost-sharing

and deductible provisions. Many prescription

drugs covered prior pre-deductible, subject to

co-payment.

Laboratory

services, including

routine blood

screening and

routine pathology

screening

No coverage for any laboratory

services that fall outside of the

DPC’s on-site lab or the lab that

has entered into an agreement

with the DPC.

Some laboratory services that fall within the

ACA ‘s preventive services mandates covered

at no out-of-pocket cost to consumer:

Other laboratory services covered, some pre-

deductible, subject to health plan copayment

and deductible provisions.

Specialist services

No coverage

Covered, some pre-deductible, subject to

health plan co-payment and deductible

provisions

Emergency

Department

No coverage

Covered, subject to health plan co-payment

and deductible provisions

Hospitalization

No coverage

Covered, subject to health plan co-payment

and deductible provisions

UW Health Policy Group 11 | 20

B. Value-Added Calculation for Consumers

The monetary value of a DPC arrangement to a consumer would depend on comparison of these two

cost bundles:

Situation 1: DPC plus HDHP/HSA

Situation 2: Standard Insurance Coverage

Costs to Consumer

• Monthly DPC fee

• Monthly HDHP premium with HSA deposits

• Out-of-Pocket costs for specialist, lab,

prescription drug, and hospitalization services

pre-deductible

Costs to Consumer

• Monthly premium for standard insurance

• Out-of-pocket costs not covered by standard

insurance.

Note also that the bills considered by the Legislature in the 2017-19 session specify that direct primary

care payments may not count towards the patient’s insurance deductibles or out-of-pocket expenses. A

consumer using an insurance plan rather than a DPC would have their payments for primary care

services applied toward any deductibles. Table 2 compares cost-exposure for a consumer across the

range of services, pre- and post- deductible.

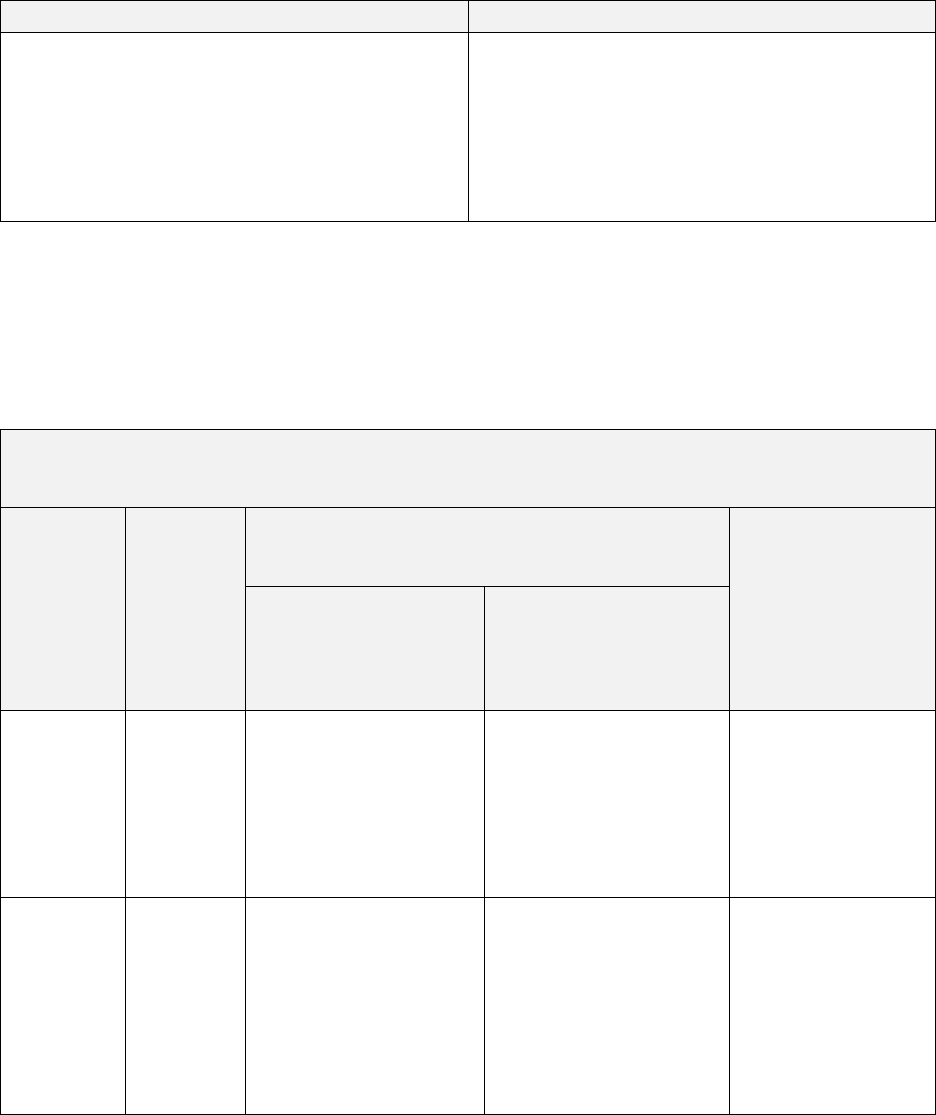

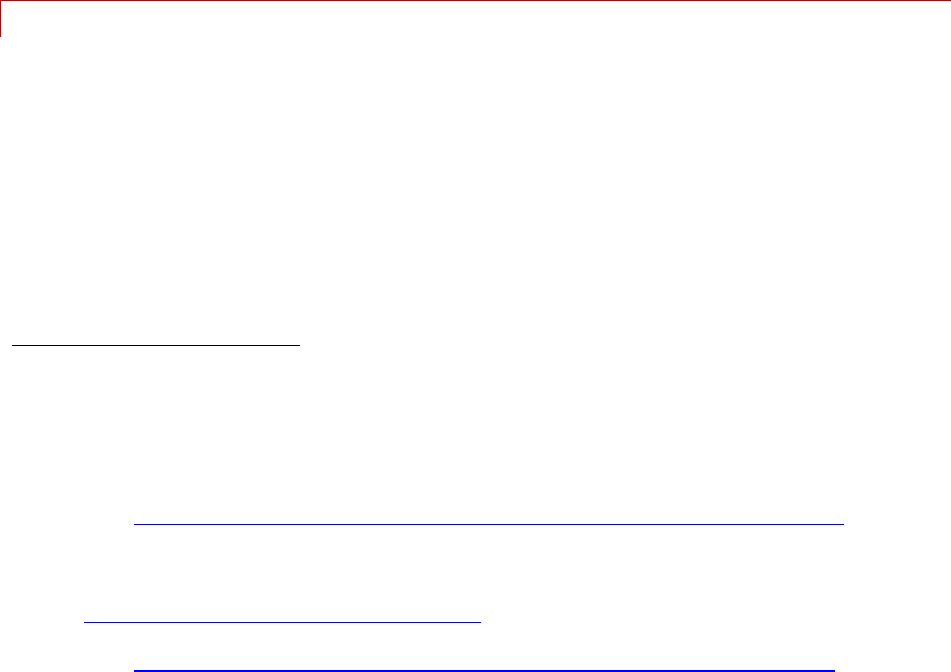

Table 2: Sources of Coverage for Health Care Services,

DPC with HDHP compared to Standard Health Insurance Plan

Preventive

Services

(ACA

mandated)

Pre-Deductible

Post Deductible

Primary care

office visits:

Specialist, lab, imaging,

prescription, emergency

department

Situation 1:

DPC plus

HDHP

DPC fee

HDHP

covered

services

DPC subscription fee

Consumer out-of-pocket

(or HSA payments)

DPC fee

Cost-sharing

provisions for other

services, up to HPDP

out-of-pocket

maximum

Situation 2:

Standard

Insurance

Coverage

Standard

plan

covered

services

Covered pre-deductible,

often subject to co-

payments; copayments

applied toward

deductible

Pre-deductible, often

subject to co-pays;

emergency department

may or may not be

subject to deductible

copayments applied

toward deductible

Cost-sharing

provisions, up to

out-of-pocket

maximum

UW Health Policy Group 12 | 20

Private Market: Standard Insurance Coverage vs DPC-plus-HDHP

This section compares costs to the consumer for Situation 1 (DPC and HDHP insurance plan) and

Situation 2 (Standard non-HDHP plan).

A consumer in a DPC arrangement would have to pay the DPC fees, and decide whether to enroll in a

plan that offers coverage for services not included in the DPC contract, such as specialist and hospital

services. The relative monetary value will depend on whether a consumer has overall out-of-pocket

costs lower than what would be required under standard insurance after copayments, and restrictions

on covered benefits. This will depend on how many referral, specialty, or hospital services, laboratory,

imaging, and prescription drugs a patient needs in a given year beyond what the DPC offers. A

consumer with a HDHP must pay the full retail pricing, or discounted rates negotiated by their insurer,

for these additional services and medications until they meet the full amount of their deductible.

Table 3 displays the premiums for 2018 ACA-compliant coverage at the various ACA metal levels in

Wisconsin, before and after federal premium subsidies.

38

Most consumers (over 80%) purchasing

individual coverage qualify for premium subsidies, while 43% also qualified for cost-sharing reductions.

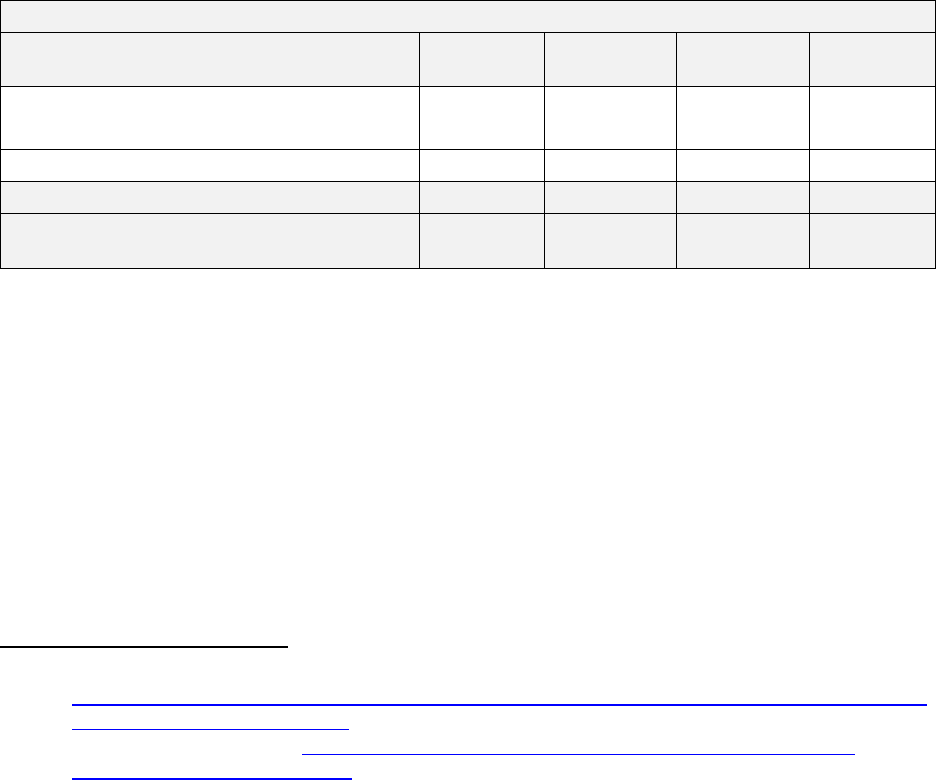

Table 3. Wisconsin 2018: Premiums, Before and After Federal Premium Subsidy, by Metal Level

Wisconsin 2018:

ACA-compliant e health plans on Exchange

Overall

Bronze Plan

Silver Plan

Gold Plan

Percent of Consumers Selecting Plans

(225,435 total consumers)

100%

33.4%

54.1%

11.4%

Average Premium (monthly)

$750

$626

$833

$759

Average premium after Subsidy (monthly)

$190

$209

$158

$278

Average Premiums after APTC among

consumers receiving APTC (monthly)

$106

$74

$105

$193

The deductive and scope of coverage HSA model and standard insurance model are comparable.

39

However, standard insurance plans generally offer coverage, prior to the consumer meeting deductible,

for a range of common services. For example, a Wisconsin standard commercial plan with a $5,000

deductible may cover primary and specialist office visits before deductible with a $25 copayment. The

HSA model generally requires the consumer to meet the full deductible before covering any services,

other than the ACA mandated preventive health services.

Table 4 displays the deductibles and copayments for sample HSA plays offered by Wisconsin issuers. The

HSA model offers potential savings due to its likely lower up-front premiums (although these premiums

may not be substantially lower if the consumer receives federal premium subsidies). The savings in

38

CMS, US DHHS. 2017 and 2018 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files.

https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Marketplace-

Products/Plan_Selection_ZIP.html

39

See national averages, reported at https://www.healthpocket.com/healthcare-research/infostat/2018-

obamacare-premiums-deductibles

UW Health Policy Group 13 | 20

premium payments for the HSA/HDHP-participant, in order to deliver value, will need to exceed the out-

of-pocket costs the consumer incurs that a standard might have covered.

Table 4. Sample 2018 HSA Individual and Family Plan Options, Wisconsin

40

Bronze HSA

Silver HSA

Gold HSA

Deductible – In Network (Single/Family) $6,650/$13,300 $3,200/$6,400 $1,800/$3,600

Out-of-Pocket– In Network

(Single/Family)

$6,650/$13,300 $6,550/$13,100 $6,550/$13,100

Coinsurance In-Network 0% 25% 10%

In-Network Preventive Care $0 $0 $0

In-Network Primary Care, Specialist,

Urgent Care, Emergency Room, and

Prescription Drugs

Deductible

Deductible with

Coinsurance

Deductible with

Coinsurance

Medicaid Coverage: Standard Medicaid vs. DPC plus Medicaid-wraparound

Table 5 displays the average benefit cost by eligibility group in Medicaid, for 2015-16.

41

Table 5. Average annual Wisconsin Medicaid per member per month cost, 2015-16

Average Annual Per Member

Cost

Average Per Member Per

Month (calculated by author)

Children

$1,762

$147

Parents

$4,128

$344

Childless Adults

$5,770

$481

BadgerCare Plus Total

$3,228

$269

The costs and benefits to the state budget would depend on the up-front costs of paying for the DPC

contracts, the extent to which primary care may be “carved out” of current managed care contracts, and

any reductions or increases in other medical or pharmacy service costs for individuals enrolled in

Medicaid DPC. As an example, if DHS implemented a DPC benefit that cost $70 per month (as

40

Samples from Quartz Health Plans:

https://unityhealth.com/docs/default-source/docs/uh01445-(0817)-primeoverview-

v5_final56382ad2b2e76b509b7eff0000a05e52.pdf?sfvrsn=2

and from Common Ground Healthcare Cooperative: https://www.commongroundhealthcare.org/our-

plans/individuals-families/

41

Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau. Medical Assistance and Related Programs (BadgerCare Plus, EBD Medicaid,

Family Care,and SeniorCare) Information Paper 41. Table 1.5: 2015-16 Total and Average Benefit Cost by

Eligibility Group. January 2017.

http://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/misc/lfb/informational_papers/january_2017/0041_medical_assistance_a

nd_related_programs_informational_paper_41.pdf

UW Health Policy Group 14 | 20

contemplated in the original Wisconsin bill), the DPC model would need to reduce other Medicaid

benefit costs by at least $70 per month in order to save costs. This would depend on several factors:

• Do the health plans continue to price in the required preventive services into their

premiums, apart from the DPC, or carve out these services and rely on the DPC to provide

them?

• Does DPC provide and participate in after-hours care, or do their enrolled patients rely on

other sources of care for after-hours services?

• How much does the DPC rely on laboratory, imaging, and specialist referrals?

• Does the DPC model avert other specialty, lab, imaging, referral, and hospital costs that

would otherwise accrue to the Medicaid program?

V. Health System Value: Utilization, Quality, and Outcomes

Section IV details how the DPC value proposition depends on how much a DPC can handle a consumer’s

total health care needs relative to how much a consumer would need to spend outside of the monthly

DPC subscription fee to have sufficient coverage. This section considers how DPC might affect the

demand for and use of health care services, the quality of services delivered, and how this might relate

to health care and cost outcomes.

A. Volume of Care and Utilization

Most health care costs are concentrated in a small proportion of high-cost, high need patients – often

referred to as super-utilizers.

42

In fact, and the costliest five percent of patients account for half of all

health care spending. The superutilizer populations generally have complex chronic and acute needs. It

is not clear whether this population, their health care needs, and their costs can be managed within a

primary care office setting, as many of their needs require significant and intensive specialist

management and care coordination.

Most consumers, however, use relatively few health care services. About half of all U.S. residents visit

the physician three or fewer times in a year, while another quarter incur 4-9 visits annually.

43

(Table 6)

These include all visits – for primary and specialty care services. On a national level, 51% of those visits

occur with primary care physicians, 28% with another medical specialist and 21% with a surgical

42

Altarum Healthcare Value Hub. Addressing the Unmet Medical and Social Needs of Complex Patients.Reserach

Brief No. 17. February 2017.

http://www.healthcarevaluehub.org/advocate-

resources/publications/addressing-unmet-medical-and-social-needs-complex-patients/

43

U.S. CDC. Health, United States 2016. Table 65 Health care visits to doctor offices, emergency departments, and

home visits within the past 12 months, by selected characteristics: United States, selected years 1997–

2015. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus16.pdf#065

UW Health Policy Group 15 | 20

specialist;

44

on average in 2015, U.S. residents incurred 1.6 visits per year with primary care physicians,

and 1.5 visits per year to medical and surgical specialists.

45

(Table 7)

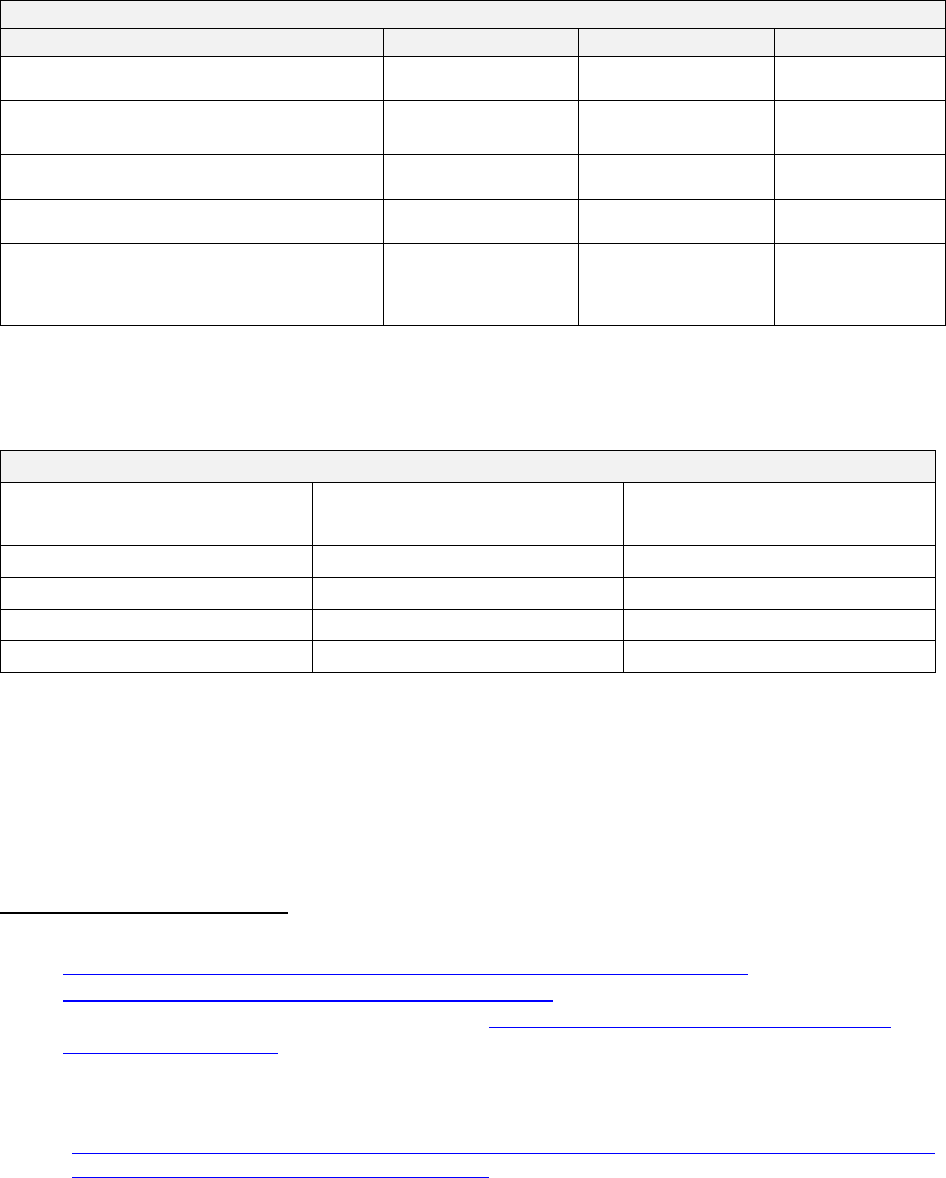

Table 6. Average Number of Physician Office Visits Annually

None

1-3

4-9

10 or more

Total Population

15.0%

48.4%

23.7%

12..8%

Medicaid

12.4%

43.4%

25.4%

18.8%

Table 7. Physician Office Visits 2015: Percent of Total Visits and

Average Number of Annual Visits Across Specialties

Specialty Type

Percent of Total

Visits

Average Number of

Visits

Primary Care

51.0%

1.60

Medical Specialty

28.4%

0.89

Surgical Specialty

20.6%

0.65

These figures suggest that most U.S. residents incur fewer than five primary care visits annually, and

about half would incur none, or only one or two visits, for which they would make use of their DPC

contract provider. The other half of their medical needs, along with the lab, imaging, and pharmacy

services associated with their primary care visits, may fall outside of the DPC contract and depend on

their insurance coverage and related cost-sharing exposure.

B. DPC Impact on Health Outcomes and Quality

Among recent trends in health care improvement and cost-containment, efforts have come to focus on

reducing overuse of services that lack a clear medical basis, which incur costs (and possible medical

harm) that exceed likely benefit.

46

It will be important to understand the degree to which DPC practices

provide evidence-based services to their members and avert costly services outside of the DPC that their

patients would otherwise have incurred.

DPC advocates assert that physicians are able to provide coordinated and comprehensive care, allow

access to physicians at any time, permit longer appointments with the physician, offer chronic disease

management, and provide cost-effective convenience.

47

As noted above, it remains unclear whether

44

National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2015 State and National Summary Tables. Table 1. Physician office

visits, by selected physician characteristics.

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2015_namcs_web_tables.pdf

45

National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2015 State and National Summary Tables. Table 1. Physician office

visits, by selected physician characteristics.

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2015_namcs_web_tables.pdf

46

Cassel CK, Guest JA. Choosing wisely: helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care.

JAMA. 2012;307(17):1801-1802.

47

Walton P. 5 benefits that concierge doctors offer. Clearwater, FL: American Academy of Private Physicians; 2014.

http://aapp.org/blog/5-benefits-that-concierge-doctors-offer

UW Health Policy Group 16 | 20

the extra time and additional visits available to the current DPC user population do in fact improve

health outcomes and avert other specialty and referral services that would otherwise occur. The

American College of Physicians, in its 2015 position paper,

48

warns as follows:

Retainer practices note that they are able to see their patients more often throughout the year. Once

again, there is no evidence to suggest that this is always necessary or effective. With all of the

“amenities” offered by these practices, it is important to do a cost–benefit analysis to understand the

true effect of the “extras” in a practice. At this time, no research or data are available to indicate

that many of these amenities in a practice yield better clinical outcomes. It is important to be aware

of the potential for overutilization of physician time and medical services.

DPCs not participating in insurance may not participate in quality measurement programs,

interoperability with other electronic health record systems, and the associated effect on quality and

outcomes.

49

It will be important for the DPC to report its encounter data to the health plan or other

monitoring entity, to allow ongoing quality review, and report its Medicaid and performance measures.

Lacking insurance regulation or payer oversight, DPC practices theoretically lack accountability to

professional review; “bad actors” could overload their practices with subscribing patients and

compromise on quality of care. Wisconsin’s DPC bill, as amended, would have relied on insurance plans

to regulate such conduct, specifying that direct primary care providers who wish to be part of an

insurance network must comply with the insurance carrier’s terms of participation.

VI. How do DPCs affect the primary care workforce?

U.S. primary care physicians maintain a practice panel of about 2,300 patients,

50

while DPCs typically

limit their patient panels to several hundred patients.

51,52,53

Direct primary care (DPC) allows physicians

to reduce their patient panel size and the daily volume of patients, while maintaining a competitive

income.

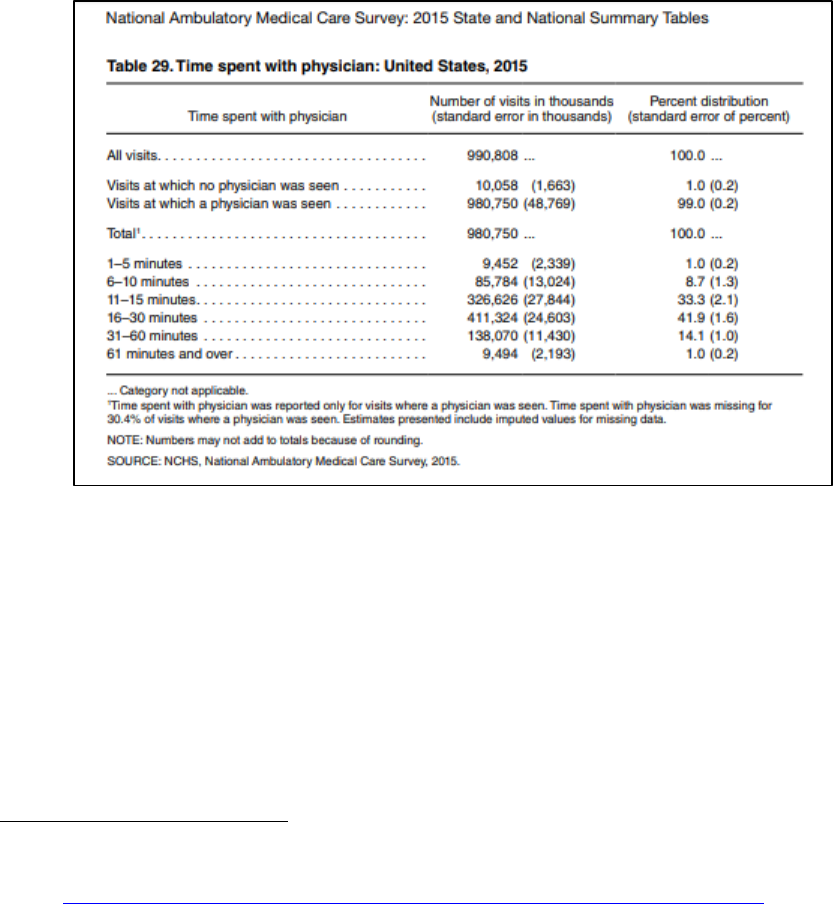

Proponents of DPC point to this decreased panel size, and increased time a provider can spend with

each patient, as one of the primary benefits of this model. Table 8 displays the time spent with

physicians in U.S. office visits, as reported in 2015.

54

About half last fewer than 15 minutes, 42% last up

48

Doherty R. Assessing the patient care implications of “concierge” and other direct patient contracting practices:

a policy position paper from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(2):949–952.

49

Ibid.

50

Altschuler J, Margolius D, Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K. Estimating a reasonable patient panel size for primary

care physicians with team-based task delegation. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(5):396–400.

51

Qamar S. Direct primary care and concierge medicine: they're not the same KevinMD.com [blog]. 24 August

2014. www.kevinmd.com/blog/2014/08/direct-primary-care-concierge-medicine-theyre.html

52

Alexander GC, Kurlander J, Wynia MK. Physicians in retainer (“concierge”) practice. A national survey of

physician, patient, and practice characteristics. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(12):1079-1083.

53

Eskew P. In defense of Direct Primary Care. Am Pract Manag. 2016 Sep-Oct;23(5):12-14.

https://www.aafp.org/fpm/2016/0900/p12.html

54

NCHS, National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 2015. Table 29, Time spent with physicians: United States,

2015. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2015_namcs_web_tables.pdf

UW Health Policy Group 17 | 20

to 30 minutes, and about 15% last up to an hour. This will vary by specialty, with primary care specialties

averaging about 20 minutes overall.

55

In comparison, survey reports show that DPC physicians spend an average of 35 minutes with each

patient visit, and patients in the practice average four visits annually.

56

However, this comparison of

averages does not necessarily reflect an actual upgrade in service for each patient. The overall U.S.

average includes all patients, including those with high acuity and intensive service needs, averaged with

those that have few health care needs. Recall, as detailed above, that most of the population requires

very few health care visits annually while a minor proportion require a large number of visits.

Table 8.

Those persons with higher health care services needs very likely receive longer and more visits, while

those with fewer needs receive fewer and shorter visits. As well, primary care providers may refer those

with higher health care needs out to specialists for their additional health care visits. Some of those

referral services may be unnecessary and could be appropriately handled in the primary care setting,

while some may quite necessary given the needs of the patient.

In contrast, the DPC visit average includes only the limited population of patients enrolled in the DPC

subscription model. The DPC model, at this point, may in fact be enrolling an overall healthier patient

population; existing studies show enrolment of smaller proportions of African American and Hispanic

55

NCHS, National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 2015 Table 30. Time spent with physician, by physician

specialty: United States, 2015.

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2015_namcs_web_tables.pdf

56

Eskew P, Klink K. Direct primary care: practice distribution and cost across the nation. J Am Board Fam Med.

2015;28(6):793–801.

UW Health Policy Group 18 | 20

residents, and a tendency to locate in wealthier communities.

57

DPC patients may include the “worried

well” who appreciate DPC practice amenities and a relationship with the physician. But evidence does

not yet exist to show that, for these patients, more time with the physician or more visits improve

outcomes, or whether this population in fact needs these visits.

The extra time and visits provided by the DPC may not, for a generally well population, avert other

specialty or referral costs that would otherwise been incurred. If not, the DPC model would not

necessarily produce health care savings or reduce overall demand for services.

58

The DPC model lowers the patient-to-provider ratio, meaning a community needs more providers to

accommodate its population base at the primary care level. DPCs would need to reduce overall service

demand in the community to avoid creating or exacerbating workforce capacity shortages. If the extra

time and visits that DPCs provide for their patients do in fact alleviate need and demand for specialty

services, then the model could have a beneficial effect on the health care workforce.

DPC advocates also argue that the model can improve physician satisfaction and retention in practice.

They point to studies showing that U.S. physicians are among the least satisfied in the world.

59

Primary

care physicians express frustration with the limited the time they can spend with each patient and with

income stability,

60

along with the amount of time their practices spend on administrative burdens

related to insurance or payment claims.

61

DPC may encourage more physicians to stay in practice or

pursue primary care specialties.

62

Whether such potential primary care physician retention, or potential

increase in the supply, can sufficiently offset the reduction in patient-to-provider ratio within their

practices, remains uncertain.

57

Weisbart ES. Is Direct Primary Care the Solution to Our Health Care Crisis? Fam Pract Manag. 2016 Sep-

Oct;23(5):10-11. https://www.aafp.org/fpm/2016/0900/p10.html

58

Doherty R. Assessing the patient care implications of “concierge” and other direct patient contracting practices:

a policy position paper from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(2):949–952.

59

Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey of Primary Care Physicians. New York, NY: The

Commonwealth Fund; November 2012.

http://www.commonwealthfund.org/interactives-and-data/chart-

cart/in-the-literature/2012-a-survey-of-primary-care-doctors-in-ten-countries/physician-satisfaction-with-

practicing-medicine

60

Friedberg MW, Chen PG, Van Busum KR, Aunon F, Pham C, Caloyeras J, et al. Factors affecting physician

professional satisfaction and their implications for patient care, health systems, and health policy. RAND.

2013. www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR439.html

61

Osborn R, Moulds D, Schneider EC, et al. Primary Care Physicians In Ten Countries Report Challenges Caring For

Patients With Complex Health Needs. Health Affairs 2015; 34(12): 2104-2112.

62

Doherty R. Assessing the patient care implications of “concierge” and other direct patient contracting practices:

a policy position paper from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(2):949–952.

UW Health Policy Group 19 | 20

VII. Conclusion: Questions for Consideration

Many states, including Wisconsin, have adopted or are considering legislation to define DPC

arrangements as medical services rather than an insurance plan, and provide a framework for Medicaid

coverage of DPC services. The evidence has not yet established the effect of DPC on health care

spending, quality, or access.

As these discussions continue in Wisconsin, particularly regarding direction of Medicaid funding,

lawmakers may want to consider some of the following questions regarding the private insurance

market to guide their decisions:

Will DPC duplicate benefits provided through other private insurance coverage – particularly the

required preventive services that all insurance products must offer.

Will insurance premiums and products carve-out the preventive care component included in the

DPC subscription? If so, what is the effect on care coordination?

What are the actuarial projections for use of DPC services within the subscription fee relative to

the cost of other laboratory, imaging, prescription, drug, specialist referral, and hospital services

for which the consumer will experience cost exposure?

Does DPC avert additional care needs, such as hospitalization or prescription drug costs, such that

the consumer does not incur out-of-pocket costs that would have been covered under a standard

insurance plan?

Does this model reduce utilization and, thereby, costs in the health care system as a whole?

Can the DPC model sufficiently manage the care of high needs patients that currently incur most

of the costs within health care generally and specifically within the Medicaid program? Or

Are DPCs better positioned as an option for generally healthy, lower needs populations and, if so,

where do DPC’s find cost savings?

Given existing and projected primary care provider shortages, what effect would DPC expansion

have on access to care?

A Medicaid-DCP pilot program may additionally focus on the following questions:

• Would DPC affect the types of services needed by Medicaid enrollees, and would that the DPC

model generate savings to compensate for the cost of the DPC contracts?

• How would DPC affect current managed care contracts, and would carving out primary care

from those contracts affect care coordination and/or quality measurement?

UW Health Policy Group 20 | 20

VIII. Other Background Reading

1. American Academy of Family Practice: Director Primary Care.

https://www.aafp.org/practice-

management/payment/dpc.html

2. Baror R. Is Direct Primary Care the Future? Federal Bar Association.

http://www.fedbar.org/Sections/Health-Law-Section/Health-Law-Checkup/Is-Direct-Primary-Care-

the-Future.aspx

3. Engelhard CL Is direct primary care part of the solution or part of the problem? The Hill. October 13,

2014.

http://thehill.com/blogs/pundits-blog/healthcare/220527-is-direct-primary-care-part-of-the-

solution-or-part-of-the#bottom-story-socials

4. Friedberg MW et al. Effects of Health Care Payment Models on Physician l Practice in the United

States. RAND Corporation, 2015. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR869.html

5. Huff C. 2015. Affordability, Access, Models Of Care & More Direct Primary Care: Concierge Care For

The Masses. Health Affairs Vol. 34 (12): 2016-2019.

6. Kirchheimer S. The Doctor Will See You but Not Your Insurance. AARP. August 6, 2013.

https://www.aarp.org/health/health-insurance/info-08-2013/direct-primary-care.html

7. Levy R. Back to the Future: Implications of Recent Developments in Physician Payment

Methodologies. Journal of Health Care Compliance, September – October 2012, pp 55-71.

http://www.dickinson-wright.com/-/media/files/news/2012/09/back-to-the-future-implications-of-

recent-develo__/files/jhcc_05-12_levy/fileattachment/jhcc_05-12_levy.pdf?la=en

8. Luthra S. Would Paying Your Doctor Cash Up Front Get You Better Care? NPR, January 13, 2016.

https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/01/13/462898517/can-concierge-medical-care-

work-for-the-middle-class

9. Ramsey L. A new kind of doctor's office that doesn't take insurance and charges a monthly fee is

'popping up everywhere' — and that could change how we think about healthcare. Business Insider.

March 17, 2018.

http://www.businessinsider.com/direct-primary-care-no-insurance-healthcare-

2018-3

10. Rosenbaum S. Law and the Public’s Health. Public Health Reports, Jan-Feb 2011, Vol 126: 130-135.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3001813/

11. Rubin R. Is Direct Primary Care a Game Changer? JAMA. 2018;319(20):2064-2066.