This is a prepress version of the statement that will appear in final form in AJHP at a future

date. That statement will replace this preliminary version when it is final.

ASHP Statement on the Role of Pharmacists in Primary Care

Position

ASHP believes that pharmacists have a role in meeting the primary care needs of patients

directly and in collaboration with other healthcare providers. Primary care pharmacy practice is

the provision of integrated, accessible healthcare services by pharmacists who are accountable

for addressing medication needs, developing sustained partnerships with patients, and

practicing in the context of family and community.

1

Primary care pharmacy practice is

accomplished through the provision of direct patient care and medication management

services (MMS) for ambulatory patients, development of long-term relationships, coordination

of care, patient advocacy, wellness and health promotion, triage and referral, and patient

education and self-management. The primary care pharmacist provides primary care services in

a variety of settings, including institutional, private, and community-based clinics. Primary care

pharmacists help offset deficits in the primary care workforce caused by a shortage of

physicians and other healthcare providers, particularly for underserved populations, by

providing MMS in interdisciplinary team-based settings as well as in areas such as telehealth,

population health, transitions of care, employer-based services, lifestyle medicine, accountable

care organizations, and public health. Primary care pharmacists are often embedded into the

primary care practice to provide MMS.

Many states allow pharmacists to partner with physicians via collaborative practice

agreements (CPAs) that enable physicians to delegate specific tasks (e.g., initiation, titration,

and discontinuation of medications; laboratory monitoring of therapy; medication and disease

state monitoring) to a pharmacist. ASHP supports passage of federal and state laws and

regulations that authorize pharmacists as providers within collaborative practice and that

facilitate reimbursement for services provided by pharmacists.

2

Further, ASHP advocates that

pharmacists be recognized as providers in federal, state, and third-party payment programs.

Provider recognition would facilitate direct billing for services provided, similar to billing by

physicians, nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists, and physician assistants.

3

Until that

ASHP Statement on the Role of Pharmacists in Primary Care 2

recognition is obtained, ASHP encourages healthcare organizations to use a variety of models to

ensure the financial sustainability of services provided by primary care pharmacists, such as

through indirect funding, incident-to billing, and increased use of the limited direct insurance

billing opportunities available. Several states have passed pharmacist provider status laws or

reimbursement parity laws allowing for reimbursement for direct patient care pharmacist

services by state Medicaid and/or commercial plans.

4

As pharmacists become core members of the primary care workforce, credentialing and

privileging with payers and healthcare organizations will be essential. As credentialed providers,

pharmacists are able to both provide patient care services and contribute to the financial

sustainability of those services. Privileging protects their employing organizations from legal risk

and ensures patients receive care from qualified and competent providers. ASHP recommends

the use of credentialing and privileging in a manner consistent with other healthcare

professionals to assess a pharmacist’s competence to engage in patient care services.

5

Credentialing and privileging systems already exist for physicians, physician assistants, and

nurse practitioners, but are far less common for pharmacists. Integration of pharmacists into

existing processes will enable the profession to function collaboratively and in parallel with

their colleagues and assist in preparing for pharmacist provider status. There are many

opportunities for pharmacists who practice in primary care settings to seek additional

credentials beyond a pharmacy degree and licensure, and certain credentials may be required

to obtain specific privileges to provide MMS. The variety of state requirements to provide

primary care pharmacist services can be a barrier to patient access to those services, thus

standardized credentialing is needed.

Primary healthcare

A 2021 National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine report defined high-quality

primary care as “the provision of whole-person, integrated, accessible, and equitable health

care by interprofessional teams that are accountable for addressing the majority of an

individual’s health and wellness needs across settings and through sustained relationships with

patients, families, and communities.”

6

The report stated that high-quality primary care is a

ASHP Statement on the Role of Pharmacists in Primary Care 3

critical component to achieving the quadruple aims of healthcare: enhancing the patient

experience, improving population health, reducing costs, and improving the health care team

experience.

6

Primary healthcare is a comprehensive and holistic care approach to health and well-being

that is centered on and tailored to the needs of individuals, families, and communities. The

World Health Organization (WHO) has developed a three-component definition of primary care:

1. Meeting people’s health needs through comprehensive promotive, protective,

preventive, curative, rehabilitative, and palliative care throughout the life cycle,

prioritizing key healthcare services aimed at individuals/families through primary care

and the population through public health functions as the central elements of

integrated health services.

2. Systematically addressing the determinants of health (social, economic, environmental,

as well as people’s characteristics and behaviors) through evidence-informed public

policies and actions across all sectors.

3. Empowering individuals, families, and communities to optimize their health, as

advocates for policies that promote and protect health and well-being, as co-developers

of health and social services, and as self-carers and care-givers to others.

7

Primary care pharmacy practice is the provision of integrated, accessible healthcare services by

pharmacists who are accountable for addressing medication needs, developing sustained

partnerships with patients, and practicing in the context of family and community.

1

This

practice is accomplished through direct patient care and medication management for

ambulatory patients, development of long-term relationships, coordination of care, patient

advocacy, wellness and health promotion, triage and referral, and patient education and self-

management. The primary care pharmacist may practice in institutional, private, and

community-based clinics involved in the provision of direct care to diverse patient populations.

Services provided by primary care pharmacists

Primary care pharmacists may help to offset deficits in the primary care workforce, including

the physician shortage, by providing MMS in interdisciplinary team-based settings as well as

ASHP Statement on the Role of Pharmacists in Primary Care 4

areas such as telehealth, population health, transitions of care, employer-based services,

lifestyle medicine, and public health. Clinical pharmacy services may include:

• Immunizations and travel vaccines.

• Medication therapy management (MTM).

• Collaborative drug therapy management (CDTM).

• Comprehensive medication management (CMM).

• Focused specialty management of chronic diseases (e.g., anticoagulation, diabetes,

heart failure).

• Management of complex acute conditions or exacerbation of chronic conditions (e.g.,

urinary tract infection, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma).

• Provision of personalized medicine (e.g. pharmacogenomics)

• Patient counseling, education, and training.

Examples of practice settings in which pharmacists provide primary care services include:

• Accountable care organizations (ACOs)

• Community-based or free clinic

• Community pharmacy

• Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC)

• Hospital-based outpatient clinic

• Indian Health Service clinic

• Managed care integrated system

• Outpatient clinic associated with academic medical center

• Patient-centered medical home (PCMH)

• Private practice physician clinic

• Rural health clinic (RHC)

• Self-insured employee clinic

• Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center

ASHP Statement on the Role of Pharmacists in Primary Care 5

MMS. Primary care pharmacists are often embedded into the primary care practice to

provide MMS. MMS has been defined by the Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners (JCPP)

as “a spectrum of patient-centered, pharmacist-provided, collaborative services that focus on

medication appropriateness, effectiveness, safety, and adherence with the goal of improving

health outcomes.”

8

For the purposes of this statement, MMS “encompasses a variety of terms,

such as medication therapy management (MTM), comprehensive medication management

(CMM), and collaborative medication management,” as in the JCPP definition.

3

The pharmacist

may be an employee of the practice, a department of pharmacy, or a health professions school

or college, and may dedicate a part- or full-time effort to providing clinical pharmacy services.

Care may be provided face-to-face or via telehealth visits to manage medications for patients

with chronic illnesses such as hypertension, diabetes, chronic heart failure, asthma, chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease, anticoagulation, osteoporosis, and many others. Primary care

pharmacists often provide patient education about lifestyle choices or conduct annual wellness

visits (AWVs) for patients with Medicare. Many states allow pharmacists to collaborate with

physicians through CPAs that enable physicians to delegate specific tasks such as medication

initiation, titration, or discontinuation; laboratory monitoring of drug therapy; and referral for

medication and disease state management to the pharmacist.

Transitions of care services. The term transitions of care refers to the movement of

patients between healthcare practitioners, settings, and home as their condition and care

needs change.

9

During transitions, medication regimens are frequently changed and may

include medication discontinuation, dosage changes, and new prescriptions that can be

confusing for patients and caregivers to manage. Poor-quality transitions contribute to

medication errors, hospital readmissions, and increased healthcare costs.

9

Pharmacists in the

primary care setting can support patients and caregivers as they adjust to new diagnoses, care

plans, and medications.

Established Transitional Care Management (TCM) Current Procedural Terminology (CPT)

codes allow for billing of transitions of care services, providing a mechanism for

reimbursement.

10,11

There are three required elements to bill for TCM services:

ASHP Statement on the Role of Pharmacists in Primary Care 6

1. Interactive communication (e.g., phone, text, email) must occur with the patient

or caregiver within 2 days of discharge by a licensed clinical staff member, which

can be the primary care pharmacist.

2. Medical decision making of moderate to high complexity occurs during the

service period.

3. The patient has a face-to-face or telehealth visit within 7-14 days of discharge.

Services during TCM visits often include reviewing medical records, reconciling medications,

coordinating future visits, and providing patient education. Pharmacists may be involved with

all components of TCM, but the services can only be billed by a physician or a qualified

nonphysician provider such as a nurse practitioner or physician assistant according to current

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) rules. Inclusion of pharmacists in the definition

of a nonphysician provider would allow pharmacists to perform these services, among others,

and reduce the burden on primary care providers.

ASHP and the American Pharmacists Association (APhA) collaborated to develop the

Medication Management in Care Transitions (MMCT) Best Practices that spotlight transitions of

care models in pharmacy practice and provide resources for pharmacy leaders.

12

Successful

programs improved patient satisfaction scores and decreased readmission rates and

medication discrepancies.

12

A descriptive study that evaluated the impact of care transitions

intervention on clinical, organizational, and financial outcomes found that adding a pharmacist

to the care transitions team decreased hospital readmissions compared to usual care (9 vs.

26%) and prevented 103 admissions per year, translating to an annual savings of over $1

million.

13

Services offered through employer-based health plans. Employers may offer chronic

disease management or healthy lifestyle programs to employees as part of their human

resources benefits package. Pharmacists are essential team members who can provide chronic

disease medication management to employees enrolled in self-insured health plans. The

Asheville Project demonstrated that pharmacists who cared for City of Asheville employees

with diabetes improved patient satisfaction with their healthcare, decreased healthcare costs,

and increased the number of patients who achieved hemoglobin A1c, lipid, and blood pressure

ASHP Statement on the Role of Pharmacists in Primary Care 7

goals.

14

An evaluation of a national employer-based program offered by 10 organizations in 70

different communities indicated that pharmacists improved other diabetes-related population

health metrics, including monofilament examinations, annual dilated eye examinations, foot

self-exams, glucose self-monitoring, weekly exercise, and annual influenza vaccines.

15

Population health services. A shift to population health strategies in primary care has

been driven by increasing healthcare costs, emphasis on fee-for-service over value-based care,

and lack of widespread prevention initiatives. Primary care pharmacists who dedicate their time

to population health management focus on improving the quality of care for specific patient

populations. Specific population health metrics that warrant improvement are identified by

leaders within the PCMH, the ACO, through community health assessments, or by payers such

as Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers. Demonstration in improved quality metrics may be

linked with pay-for-performance payment bonuses, or shared savings incentives. For example,

if a metric of importance to the practice is to improve the quality of care for patients with

diabetes, primary care pharmacists can provide MMS for high-risk patients to improve

attainment of hemoglobin A1c goals.

16

Public health services. Expertise in the domain of public health is increasingly important

for the primary care pharmacist due to the impact of public care challenges such as the opioid

epidemic, unintended pregnancy with resultant negative maternal fetal outcomes, tobacco

abuse, and the COVID-19 pandemic. The Opioid and Naloxone Education (ONE) program has

demonstrated the ability of pharmacists to ensure safe opioid use, and prevent opioid misuse

and abuse, through implementing naloxone prescribing while utilizing the pharmacist’s patient

care process.

17

A growing number of states allow pharmacists to prescribe hormonal

contraception as a strategy to increase access to care and decrease negative maternal

outcomes.

18

Oregon pharmacists prescribing hormonal contraception prevented 51 unintended

pregnancies and saved Oregon Medicaid over $1.6 million.

19

As of February 2021, six states

(Idaho, Colorado, Indiana, West Virginia, Vermont, North Dakota, and New Mexico) have

authorized pharmacists to prescribe all FDA-approved tobacco cessation products, including

varenicline, to combat the negative impact of smoking on public health; Oregon and North

Dakota are currently developing regulations to implement authorizing legislation.

20

ASHP Statement on the Role of Pharmacists in Primary Care 8

Pharmacists in primary care settings are also well-positioned to identify immunization

needs of patients, provide education to promote vaccine confidence, and administer vaccines.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Resources

authorized immunizing pharmacists to administer childhood vaccines

21

and COVID-19

vaccines

22

as part of the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness (PREP) Act.

Telehealth. The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) defines telehealth

as “the use of electronic information and telecommunication technologies to support long-

distance clinical health care, patient and professional health-related education, health

administration and public health.”

23

Telehealth has been used for a variety of patient

populations, including veterans, rural patients, and patients with psychiatric conditions. The

COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the delivery of primary care services by telehealth. The federal

government established temporary measures in 2020 to increase access to telehealth during

the pandemic through the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental

Appropriations Act. In addition, CMS relaxed rules for supervision of auxiliary personnel to

allow physicians to provide “virtual” supervision in order to promote social distancing and

protect frontline healthcare workers.

Telehealth visits may be billed by physicians and nonphysician providers and are paid at

the same fee-for-service rate as in-person visits for Medicare recipients. Pharmacists may be

able to bill using certain approved telephone codes. Reimbursement may vary for Medicaid

and private insurance.

Special practice settings and patient populations

Rural health. Rural areas make up approximately 97% of the land area in the U.S., yet

account for just a little over 19% of the total U.S. population.

24

People living in rural areas are

often underserved and experience significant health disparities that can vary between

geographical regions and across socioeconomic spectra. Many of the health-related challenges

faced by rural America are amplified by the lack of adequate services, particularly primary care

providers and medical specialists. Approximately 90% of Americans live within 5 miles of a

ASHP Statement on the Role of Pharmacists in Primary Care 9

community pharmacy, creating additional opportunities for pharmacists to partner with

primary care providers and provide clinical pharmacy services for rural, underserved patients.

25

The expansion of pharmacist-delivered services in rural settings is an important strategy

to target health disparities that are more common causes of mortality for people who live in

rural communities than those living in urban areas. Chronic disease state management, MMS,

health screenings, tobacco cessation management and prescribing, medication-assisted

treatment of opioid use disorders, and lifestyle coaching through diabetes prevention programs

are examples of services that address these common health disparities and can be led by

pharmacists or enhanced through interprofessional collaboration with pharmacists as allowed

under state-specific pharmacy practice acts. Unique training programs focused on rural

pharmacy health exist at several colleges of pharmacy that focus on preparing pharmacists for

leadership roles in small and rural communities.

26

Many health systems that serve rural America receive reimbursement through all-

inclusive payment models by Medicare and many state bill Medicaid plans. However, the lack of

pharmacist recognition as an independent billable provider by the majority of payers, including

Medicare, can challenge the financial feasibility of advanced pharmacist services within these

settings.

27

Pharmacists can assist or serve a key role in grant-funded projects and programs and,

in the case of government-funded grants, can lead to perpetual funding to rural health

providers such as FQHCs, RHCs, and the Indian Health Service as a mechanism to defray

pharmacist costs. Examples of sustainable practice models that incorporate pharmacist-

delivered care in rural areas include the following:

1. Synchronous or co-visits between a pharmacist and a primary care practitioner who is

recognized as an independent billable provider.

2. Visits with a pharmacist independent of other health professionals.

3. Pharmacist involvement in comprehensive care services as part of the PCMH or

ambulatory primary care clinic care team.

4. Population health services that focus on quality improvement and can increase

reimbursement to the health system or collaborating primary care provider through

individual visits with the pharmacist face-to-face or via telehealth, including remote

ASHP Statement on the Role of Pharmacists in Primary Care 10

physiologic monitoring (examples of quality improvement measures include blood

pressure control, warfarin monitoring, glycemic control, rates of influenza

immunizations, and adherence to medication refills [e.g., statin therapy, antiplatelet

medications, oral glucose-lowering medications]).

5. Pharmacists involved in accredited Diabetes Self-Management Training (DSMT)

programs.

Partnerships between primary care providers and local community pharmacies, critical access

pharmacies, or academic institutions can increase access to essential services such as

immunization delivery, point-of-care testing, and disease state education and management to

people living in rural areas with limited access to primary care providers.

28-30

FQHCs. FQHCs are considered safety net health providers of outpatient clinical services

that receive funding from the HRSA Health Center Program to provide care to individuals in

underserved areas.

31

The primary purpose of FQHCs is the provision of primary care services in

underserved urban and rural communities. FQHCs are typically located in community health

centers but are also found in public housing primary care centers, outpatient health programs

operated by a tribe or urban Indian organization, migrant health centers, and healthcare for the

homeless centers. Among the requirements of FQHCs are the provision of a sliding fee scale

system for uninsured patients with incomes below 200% of the federal poverty guidelines,

provision of comprehensive healthcare services (which include medical, pharmacy, dental, and

behavioral health), an ongoing quality assurance program, and a governing board of directors.

32

FQHCs often need to meet the challenges of geographic, social, economic, linguistic, and

cultural patient barriers. Primary care pharmacists working in clinical roles within an FQHC can

have a tremendous impact on the care of this underserved patient population. Socioeconomic

and cultural/language barriers present unique challenges to medication therapy that

pharmacists are well suited to help overcome. Chronic diseases are common, noting a high

prevalence of hypertension, diabetes and tobacco use. The Uniform Data System requires

FQHCs to report on quality of care measures, therefore providing an opportunity for

pharmacists to assist in the design and implementation of clinical services aimed at meeting

quality benchmarks, as well as participate in the reporting process.

ASHP Statement on the Role of Pharmacists in Primary Care 11

FQHCs differ from traditional primary care practices in the way that payment is issued

for primary care encounters. An encounter payment is issued under the FQHC Prospective

Payment System (PPS) from CMS that includes medical services, supplies, and overall service

coordination provided to patients. The specific payment amount is unique to each FQHC and is

determined based on reasonable costs and cost reporting. Because the PPS is provided through

CMS, only practitioners who are recognized as healthcare providers by Medicare are eligible to

bill directly for services. Because pharmacists are not recognized as healthcare providers

federally, any eligible services provided by a pharmacist may not be billed directly but must

rather be billed by an eligible healthcare provider. Despite the limited opportunities for

pharmacists to promote sustainability through direct revenue, such as Medicare AWVs, there

are many primary care services provided by pharmacists in FQHCs that benefit the practice.

FQHCs that participate in the 340B program, which provides medication cost savings to

uninsured and underinsured patients as well as savings to the pharmacy, commonly leverage

the savings to support clinical pharmacy services (e.g., hiring or salary support of a clinical

pharmacist). Examples of services provided by pharmacists in FQHCs include:

• MTM

• 340B Program

• Specialty Pharmacy Services

• Spirometry

• Chronic Care Management (CCM) and Principal Care Management (PCM)

• Diabetes Self-Management Training (DSMT)

• Value-Based Care

• Quality Improvement/PCMH

• CDTM/Contract Agreements/Consult Agreements

• Population Health

• Medicare AWVs

• TCM

ASHP Statement on the Role of Pharmacists in Primary Care 12

Additional detailed information can be found in the ASHP Resource Center document,

“Opportunities for Sustainable Pharmacy Services in Federally Qualified Health Centers.”

33

Billing and reimbursement for primary care pharmacy services

The National Academy of Sciences recommends that payers, including Medicaid, Medicare,

commercial insurers, and self-insured employers, should shift payments toward a hybrid model

that includes fee-for-service and capitated payments, and that these models should pay

prospectively for interprofessional, integrated, team-based care.

6

Financial sustainability for

services provided by primary care pharmacists may be achieved using a variety of models. Due

to lack of federal provider status for pharmacists and subsequent inability to directly bill

Medicare as primary care providers, organizations and practices have become creative in

maintaining financial sustainability of primary care pharmacist services. Some settings utilize

indirect funding, while others take advantage of some of the limited direct insurance billing

opportunities to fund pharmacists in primary care settings. Direct billing opportunities will vary

based on the setting, hospital-based versus physician-based practices, as well as state-specific

laws and regulations. Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial health plans may reimburse

pharmacists for certain services, while some will require direct contracting with the health plan.

Several states have passed pharmacist state provider status laws and/or reimbursement parity

laws allowing for reimbursement for direct patient care pharmacist services by state Medicaid

and/or commercial plans.

4

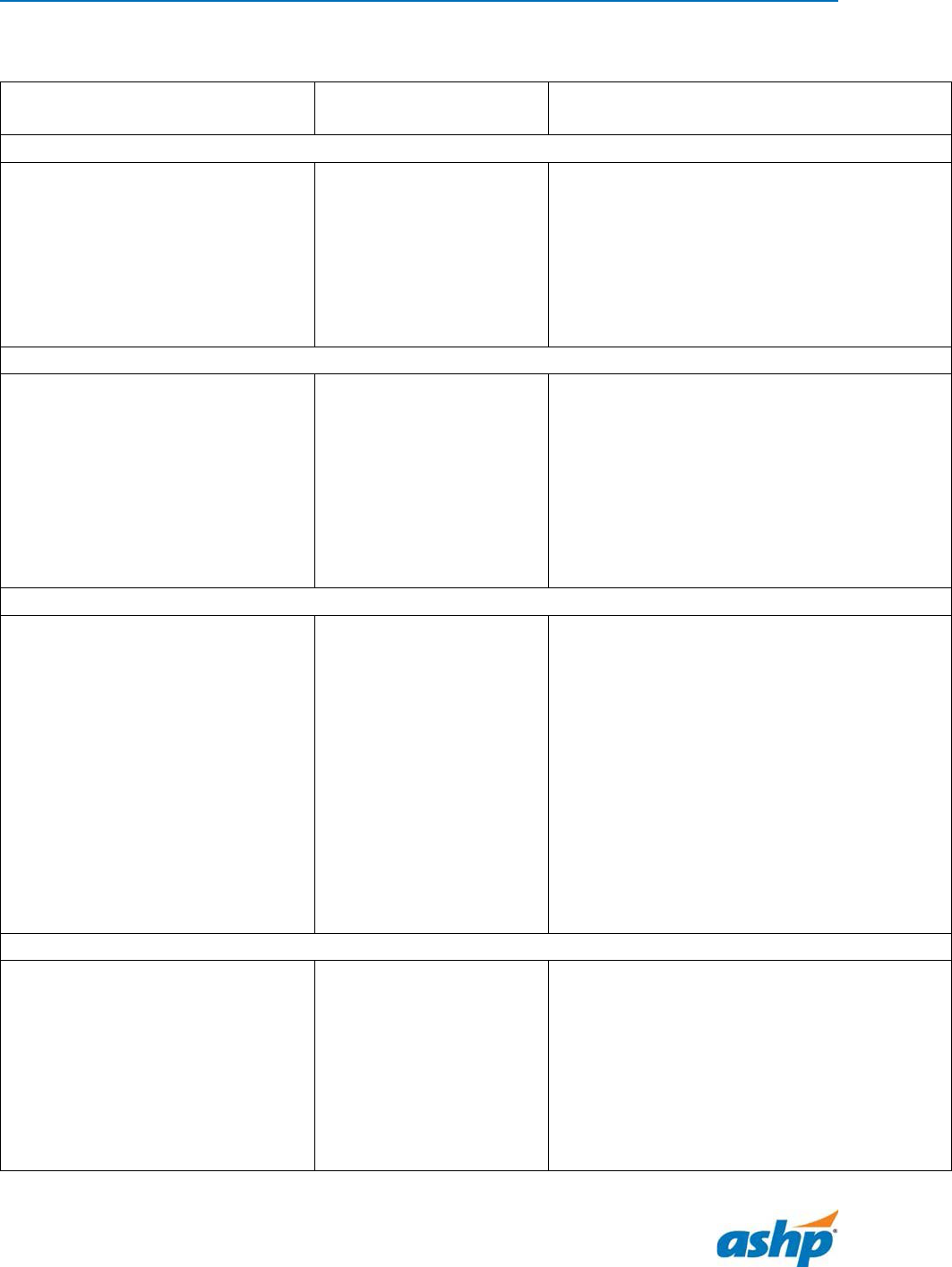

Some examples of direct and indirect billing methods are listed in

Table 1.

ASHP Statement on the Role of Pharmacists in Primary Care 13

Table 1. Examples of direct and indirect funding methods.

34

Indirect billing

Direct billing

Funding by Colleges of Pharmacy/Academic

Health Centers: shared pharmacy practice

faculty in primary care settings

Affordable Care Organizations/Managed Care

Insurance Plans

• Quality improvement/achieving quality

metrics

• Reducing medication adverse

events/improving disease management

340B Drug Program Covered Entities:

Reinvestment of 340B drug cost savings in

salary for clinical pharmacists

35

Medicare Part B/D:

• Annual Wellness Visits

• Chronic Care Management

• Facility Fee Billing (hospital-based

clinics)

36

• Incident-to (physician-based clinics)

37

• MTM contract with Medicare Part D

plans

38

• Transitional Care Management

Medicaid or Commercial Health Plans:

• State law dependent

39,40

Credentialing and privileging

As pharmacists look to fill gaps in the primary care workforce and create financially sustainable

practices, credentialing and privileging with payers and healthcare organizations are essential.

Credentialing and privileging are two separate processes. Credentialing is the process by which

an individual’s credentials (i.e., academic, license, certifications) are verified to reflect that they

have the appropriate training to practice as a pharmacist. Privileging evaluates and authorizes

providers to deliver care within a requested scope of practice. For example, if a pharmacist is

practicing in a specialty clinic such as hematology/oncology, they would have a different scope

than when practicing in a primary care setting. The privileging process ensures individuals have

the training and competency to provide the requested services in a particular specialty. Often

this verification is obtained through a peer evaluation process, whereby colleagues provide

feedback on the provider’s clinical knowledge, skills, and professional performance.

ASHP Statement on the Role of Pharmacists in Primary Care 14

With the expanding roles of pharmacists, growth in specialization, and the increased

complexity of healthcare, the credentialing and privileging process is more important than ever.

Credentialing is required by payers in order for providers to bill for services. As credentialed

providers, pharmacists are able to both provide patient care services and contribute to the

financial sustainability of the service. Privileging protects the organization from legal risk and

ensures patients receive care from qualified and competent providers. These systems already

exist for pharmacists, physician, physician assistant, and nurse practitioner colleagues;

integration of pharmacists into existing processes will enable the profession to function in

parallel and collaboratively with our colleagues and assist in preparing for provider status.

Credentials beyond pharmacy degree and state licensure

There are multiple opportunities for pharmacists who practice in primary care settings to seek

additional credentials beyond the pharmacy degree and licensure, and certain credentials may

be required to obtain specific privileges to provide MMS. For example, pharmacists who

prescribe hormonal contraception or who serve as immunizing pharmacists must complete

training and/or certificate programs to be eligible to provide those services in their state.

Certain requirements must also be met in order to enter into CPAs and vary by state.

Pharmacists who practice under a CPA in New Mexico, California, Montana, and North Carolina

are recognized as Pharmacist Clinician (NM), Advanced Practice Pharmacist (CA), and Clinical

Pharmacist Practitioner (NC and MT). The wide variety of state requirements to provide primary

care pharmacy services serves as a barrier for patient access to services, and advocacy to

standardize credentialing is needed.

Employers may require that primary care pharmacists complete a postgraduate year 1

(PGY1) and/or a PGY2 residency training program. They may also require board certification

through the Board of Pharmacy Specialties or completion of an interprofessional certificate,

such as the Certified Asthma Educator (AE-C), Certified Diabetes Care and Education Specialist

(CDCES, formerly Certified Diabetes Educator or CDE), or Certified Anticoagulation Care

Provider (CACP), among others. A listing of board certification opportunities along with

eligibility criteria for examination are listed in the Appendix. All board certification programs

ASHP Statement on the Role of Pharmacists in Primary Care 15

listed incur an examination fee, and pharmacists must achieve a passing score on the

examination and meet ongoing requirements for renewal. Benefits of board certification

include greater marketability, enhanced confidence, improved competence, increased

responsibility, and a competitive edge in job placement and advancement.

41

The Council on

Credentialing in Pharmacy has established guiding principles for post-licensure credentialing of

pharmacists.

42

Conclusion

There are many avenues in which pharmacists can become involved in primary care practice.

Identifying the ideal practice model and service offering will involve collaboration with other

healthcare providers as well as identifying a patient population and target outcome.

Achievement of federal provider status will allow pharmacists the ability to bill Medicare and

create sustainable services and financial stability, as has been demonstrated in states with

active provider status laws. As pharmacists become more involved in primary care practice,

healthcare will move closer towards the goal of optimal, safe, and effective use of medications

for all people all of the time.

References

1. Donaldson MS, Yordy KD, Lohr KN et al., eds. Primary care: America’s health in a new

era. Committee on the Future of Primary Care, Division of Health Services, Institute of

Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996.

2. ASHP policy 1715, Collaborative Practice. In: Hawkins B, ed. Best practices: positions and

guidance documents of ASHP. 2020-2021 ed. Bethesda, MD: American Society of

Health-System Pharmacists; 2021. www.ashp.org/Pharmacy-Practice/Policy-Positions-

and-Guidelines/Browse-by-Document-Type/Policy-Positions (accessed August 18, 2021).

3. ASHP policy 1502, Pharmacist Recognition as a Healthcare Provider. In: Hawkins B, ed.

Best practices: positions and guidance documents of ASHP. 2020-2021 ed. Bethesda,

MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2021. www.ashp.org/Pharmacy-

Practice/Policy-Positions-and-Guidelines/Browse-by-Document-Type/Policy-Positions

(accessed August 18, 2021).

4. National Alliance of State Pharmacy Associations. 2021 State Provider Status Mid-Year

Legislative Update (June 7, 2021). https://naspa.us/2021/06/2021-state-provider-status-

mid-year-legislative-update/ (accessed 15 Dec 2021).

5. ASHP policy 2011, Credentialing and Privileging by Regulators, Payers, and Providers of

Collaborative Practice. In: Hawkins B, ed. Best practices: positions and guidance

ASHP Statement on the Role of Pharmacists in Primary Care 16

documents of ASHP. 2020-2021 ed. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System

Pharmacists; 2021. www.ashp.org/Pharmacy-Practice/Policy-Positions-and-

Guidelines/Browse-by-Document-Type/Policy-Positions (accessed August 18, 2021).

6. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2021. Implementing High-

Quality Primary Care: Rebuilding the Foundation of Health Care. Washington, DC: The

National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25983.

7. World Health Organization. Primary health care. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-

sheets/detail/primary-health-care (accessed August 20, 2021).

8. Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners. Medication management services

definition and key points (March 14, 2018). https://jcpp.net/wp-

content/uploads/2018/05/Medication-Management-Services-Definition-and-Key-

Points-Version-1.pdf (accessed August 20, 2021).

9. The Joint Commission. 2012. Transitions of Care: The need for a more effective

approach to continuing patient care – Hot Topics in Health Care, Issue No. 1.

10. Cavanaugh J, Olson J, Parrott AM. Billing for transitional care management visits (2018).

https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/pharmacy-practice/resource-

centers/ambulatory-care/transitional-care-management-codes.ashx (accessed August

20, 2021).

11. Medicare Learning Network. Transitional Care Management Services (Publication

MLN908628, July 2021). https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-

Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/Transitional-Care-Management-

Services-Fact-Sheet-ICN908628.pdf (accessed January 31, 2022).

12. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, American Pharmacists Association.

ASHP-APhA Medication Management in Care Transitions Best Practices (2013).

https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/pharmacy-practice/resource-centers/quality-

improvement/learn-about-quality-improvement-medication-management-care-

transitions.ashx (accessed August 20, 2021).

13. Cavanaugh J, Pinelli N, Eckel S et al. Advancing Pharmacy Practice through an Innovative

Ambulatory Care Transitions Program at an Academic Medical Center. Pharmacy. 2020;

8:40.

14. Garrett DG, Bluml BM. Patient self-management program for diabetes: first-year clinical,

humanistic, and economic outcomes. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2005; 45:130-7.

15. Bunting BA, Nayyer D, Lee C. Reducing health care costs and clinical outcomes using an

improved Asheville Project model. Innov Pharm. 2015; 6:Article 227.

16. ASHP Section of Ambulatory Care Practitioners Advisory Group on Clinical Practice

Advancement. FAQ: Getting started with population health management (March 2021).

https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/pharmacy-practice/resource-

centers/ambulatory-care/population-health-faq.pdf (accessed Sep. 14, 2021).

17. Skoy E, Eukel H, Werremeyer A et al. Implementation of a statewide program within

community pharmacies to prevent opioid misuse and accidental overdose. J APhA. 2020;

60(1):117-21.

18. Rafie S, Landau S. Opening new doors to birth control: state efforts to expand access to

in community pharmacies. Birth Control Pharmacist (2019).

https://birthcontrolpharmacist.com/2019/12/21/report/ (accessed August 20, 2021).

ASHP Statement on the Role of Pharmacists in Primary Care 17

19. Rodriguez MI, Hersh A, Anderson LB et al. Association of pharmacist prescription of

hormonal contraception with unintended pregnancies and Medicaid costs. Obstet

Gynecol. 2019; 133:1238-46.10.

20. National Alliance of State Pharmacy Associations. Pharmacist Prescribing: Tobacco

Cessation Aids (February 10, 2021). https://naspa.us/resource/tobacco-cessation/

(accessed August 19, 2021).

21. Department of Health and Human Services. HHS expands access to childhood vaccines

during COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2020/08/19/hhs-

expands-access-childhood-vaccines-during-covid-19-pandemic.html (accessed August

19, 2021).

22. Department of Health and Human Services. Trump administration takes action to

expand access to COVID-19 vaccines.

https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2020/09/09/trump-administration-takes-action-to-

expand-access-to-covid-19-vaccines.html (accessed August 20, 2021).

23. Health Resources and Services Administration. Office for the Advancement of

Telehealth. https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/telehealth (accessed August 20, 2021).

24. Ratcliffe M, Burd C, Holder K et al. Defining Rural at the U.S. Census Bureau (ACSGEO-1).

Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2016.

https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/reference/ua/Defining_Rural.pdf (accessed August

20, 2021).

25. Kelling SE. Exploring accessibility of community pharmacy services. Innov Pharm. 2015;

6: Article 210. https://pubs.lib.umn.edu/index.php/innovations/article/view/392

(accessed August 20, 2021).

26. Scott MA, Kiser S, Park I et al. Creating a new rural pharmacy workforce: Development

and implementation of the Rural Pharmacy Health Initiative. Am J Health Syst Pharm.

2017; 74:2005-12. doi: 10.2146/ajhp160727.

27. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter

9: Rural Health Clinics/ Federally Qualified Health Centers (18 September 2020).

https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-

Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/clm104c09.pdf (accessed August 20, 2021).

28. Como M, Carter CW, Larose-Pierre M et al. Pharmacist-led chronic care management for

medically underserved rural populations in Florida during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev

Chronic Dis. 2020; 17:200265. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd17.200265

29. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Secretary. Third amendment to

declaration under the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act for Medical

Countermeasures Against COVID–19. Fed Reg. 52136 (August 24, 2020). Available at:

https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-08-24/pdf/2020-18542.pdf (accessed

August 20, 2020).

30. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health.

Guidance for licensed pharmacists, COVID-19 testing, and immunity under the PREP Act

(April 8, 2020). https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/authorizing-licensed-

pharmacists-to-order-and-administer-covid-19-tests.pdf (accessed August 20, 2021).

ASHP Statement on the Role of Pharmacists in Primary Care 18

31. Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA). Federally Qualified Health Centers:

Eligibility. https://www.hrsa.gov/opa/eligibility-and-registration/health-

centers/fqhc/index.html (accessed August 20, 2021).

32. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicare Learning Network Booklet.

Federally Qualified Health Center. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-

Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-

MLN/MLNProducts/downloads/fqhcfactsheet.pdf (accessed August 20, 2021).

33. Maack B, Awad M, Rosselli J. Opportunities for Sustainable Pharmacy Services in

Federally Qualified Health Centers (January 2022). https://www.ashp.org/pharmacy-

practice/resource-centers/ambulatory-care/compensation-and-sustainable-business-

models (accessed January 31, 2022).

34. ASHP Ambulatory Care Resource Center: Compensation and Sustainable Business

Models. https://www.ashp.org/Pharmacy-Practice/Resource-Centers/Ambulatory-

Care/Compensation-and-Sustainable-Business-Models. (accessed August 20, 2021).

35. Health Resources & Services Administration Office of Pharmacy Affairs.

https://www.hrsa.gov/opa/index.html (accessed August 20, 2021).

36. Parrott A, Kline E, Renaurer M et al. FAQ: Facility Fee Billing (August 2021).

https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/pharmacy-practice/resource-

centers/ambulatory-care/Facility-Billing.pdf (accessed Sep. 14, 2021).

37. Pharmacist Billing/Coding Quick Reference Sheet For Services Provided in Physician-

Based Clinics. https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/pharmacy-practice/resource-

centers/ambulatory-care/billing-quick-reference-sheet.ashx (accessed August 20, 2021).

38. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medication Therapy Management.

https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-

Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/MTM (accessed August 20, 2021).

39. New Mexico House Bill 42. Pharmaceutical Reimbursement Parity.

https://www.nmlegis.gov/Legislation/Legislation?Chamber=H&LegType=B&LegNo=42&

year=20 (accessed August 20, 2021).

40. Washington State Engrossed Substitute Senate Bill 5557.

http://lawfilesext.leg.wa.gov/biennium/2015-

16/Pdf/Bills/Senate%20Passed%20Legislature/5557-S.PL.pdf (accessed August 20,

2021).

41. Board of Pharmacy Specialties. Making a difference. https://www.bpsweb.org/impact-

of-bps-certification/making-a-difference/ (accessed August 20, 2021).

42. Council on Credentialing in Pharmacy. Credentialing and privileging of pharmacists. Am J

Health-Syst Pharm. 2014; 71:1891-1900.

Additional information

Developed through the ASHP Section of Ambulatory Care Pharmacists and approved by the

ASHP Board of Directors on February 24, 2022, and by the ASHP House of Delegates on May 19,

2022. This statement supersedes the ASHP Statement on the Pharmacist’s Role in Primary Care

dated June 7, 1999.

ASHP Statement on the Role of Pharmacists in Primary Care 19

Acknowledgments

ASHP gratefully acknowledges the following individuals for reviewing the current version of the

statement (review does not imply endorsement): Jaclyn A. Boyle, Pharm.D., M.B.A., BCACP;

Jamie J. Cavanaugh, Pharm.D., CPP; Christina E. DeRemer, Pharm.D., BCACP, BCPS, TTS, FASHP;

Ashley M. Parrott, Pharm.D., M.B.A., BCPS, BCACP; Jessica W. Skelley, Pharm.D., BCACP; and

Daniel B. Truelove, Pharm.D., BCACP, BCPS. The contributions of Kimberly A. Galt, Pharm.D.,

FASHP; Richard F. Demers; and Richard N. Herrier, Pharm.D.; to the previous version of this

statement are also gratefully acknowledged.

Authors

Melanie A. Dodd, Pharm.D., PhC, BCPS, FASHP

The University of New Mexico College of Pharmacy

Albuquerque, NM

Seena L. Haines, Pharm.D., BCACP, NBC-HWC, CHWC, FNAP, FCCP, FAPhA, FASHP

The University of Mississippi School of Pharmacy

Jackson, MS

Brody Maack, Pharm.D., BCACP, CTTS

North Dakota State University School of Pharmacy

Fargo, ND

Jennifer L. Rosselli, Pharm.D., BCPS, BCACP, BC-ADM, CDCES

Southern Illinois University Edwardsville School of Pharmacy

Edwardsville, IL

SIHF Healthcare

Belleville and O’Fallon, IL

J. Cody Sandusky, Pharm.D.

Harrisburg Medical Center

Harrisburg, IL

Mollie Ashe Scott , Pharm.D., BCACP, CPP, FASHP

UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy

Asheville, NC

Betsy Bryant Shilliday, Pharm.D., CDCES, CPP, BCACP, FASHP

UNC Health and UNC Faculty Physicians

Chapel Hill, NC

Disclosures

The authors have declared no potential conflicts of interest.

ASHP Statement on the Role of Pharmacists in Primary Care 20

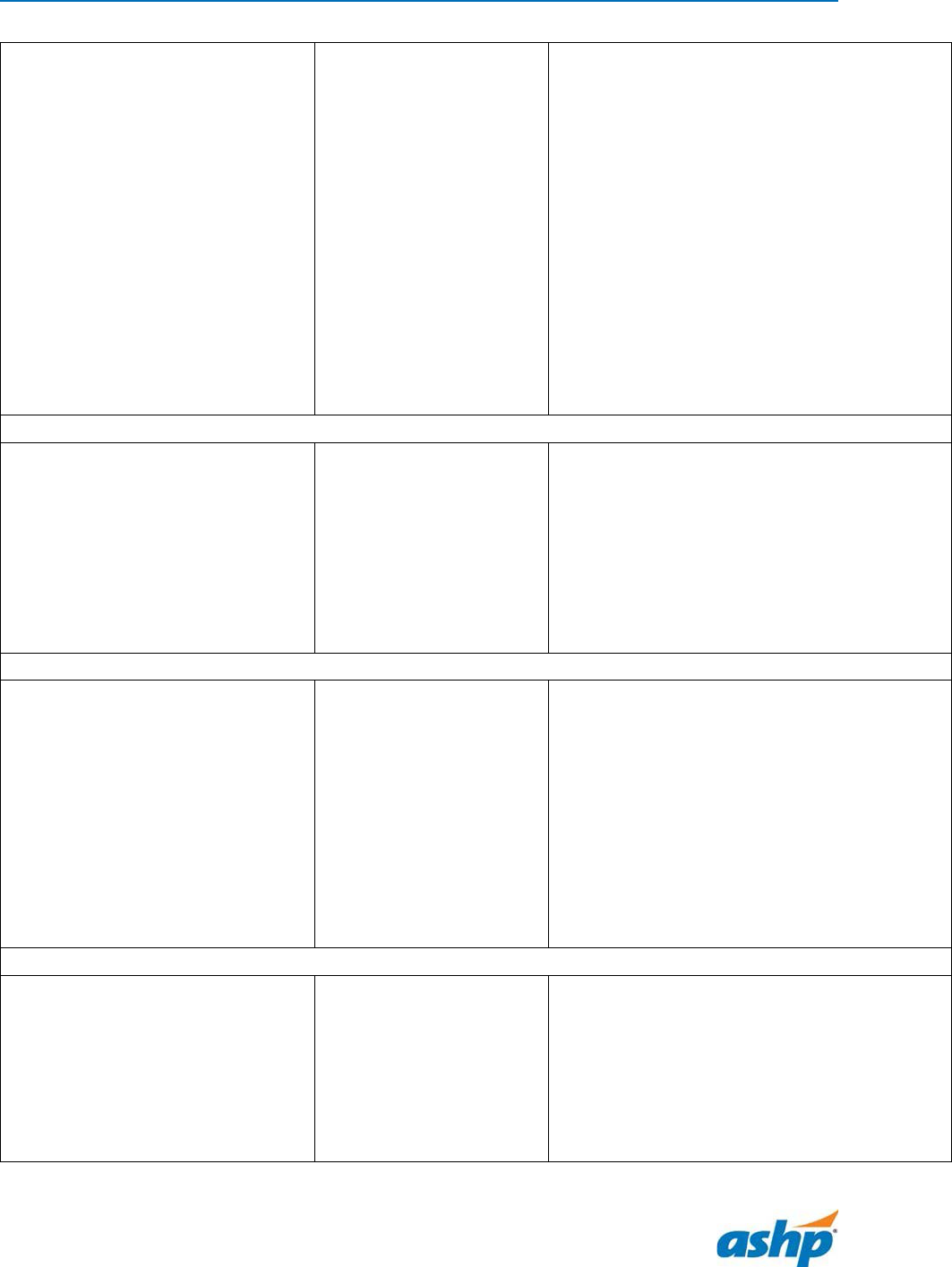

Appendix. Board Certification Opportunities for Primary Care Pharmacists

Credential

Certification Body

Eligibility Criteria for Examination

Ambulatory Care

Board Certified Ambulatory Care

Pharmacist (BCACP)

Board of Pharmacy

Specialties

https://www.bpsweb.or

g/bps-

specialties/ambulatory-

care/

• Graduation from an ACPE accredited

pharmacy program

• Current license to practice

• Demonstration of ambulatory care

practice experience

Anticoagulation

Certified Anticoagulation Care

Provider (CACP)

National Certification

Board for

Anticoagulation Care

Providers

www.ncbap.org

• Must hold professional license for two

years

• Registered nurse, nurse practitioner,

registered pharmacist, physician, or

physician assistant

• 750 hours of active antithrombotic

management within the 18 months

prior to taking the examination

Asthma

Certified Asthma Educator (AE-C)

National Asthma

Educator Certification

Board

https://naecb.com/

• Licensed healthcare professionals such

as pharmacists, physicians, physician

assistants, nurses, respiratory

therapists, pulmonary function

technologists, social workers, health

educators, physical therapists, and

occupational therapists

• Individuals providing direct patient

asthma education, counseling or

coordinating services with a minimum

of 1000 hours experience in these

activities

Diabetes

Board Certified Advanced

Diabetes Management (BC-ADM)

Association of Diabetes

Care and Education

Specialists

https://www.diabetese

ducator.org/education/

certification/bc_adm

• Registered nurse, nurse practitioner,

clinical nurse specialists, registered

dietician, pharmacist, physician

assistant, physician

• 500 clinical practice hours within 48

months of taking the examination

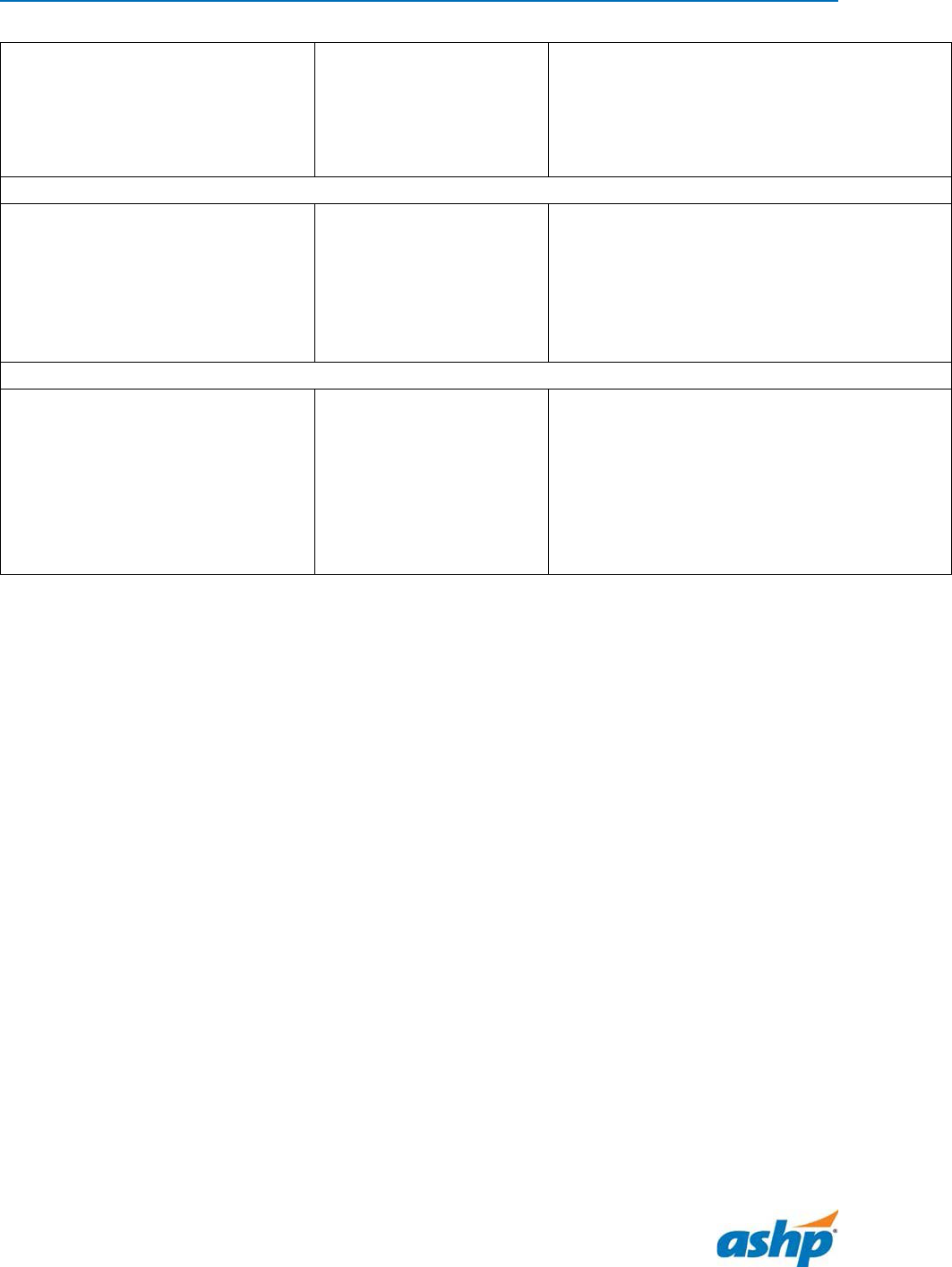

ASHP Statement on the Role of Pharmacists in Primary Care 21

Certified Diabetes Care and

Education Specialist (CDCES)*

Certification Board for

Diabetes Care and

Education

https://www.cbdce.org/

• Qualifying healthcare professional:

registered nurse, nurse practitioner,

registered dietician, pharmacist,

physician assistant, physician, and

others

• 2 years of prior professional experience

• A minimum of 1000 hours providing

diabetes care and education in the

previous 4 years with a minimum of 400

hours in the previous year

• A minimum of 15 hours of approved

continuing education focused on

diabetes in the previous 2 years

Geriatrics

Board Certified Geriatric

Pharmacist (BCGP)

Board of Pharmacy

Specialties

https://www.bpsweb.or

g/bps-

specialties/geriatric-

pharmacy/

• Graduation from an ACPE accredited

pharmacy program

• Current license to practice

• Demonstration of geriatric practice

experience

HIV

HIV Pharmacist (AAHIVP)

American Academy of

HIV Medicine

https://aahivm.org/hiv-

pharmacist/

• Pharmacist licensure

• Documentation of direct HIV care for 25

patients living with HIV within the

preceding 36 months

• Participate in the Academy’s Clinical

Consult Form

• Complete a minimum of 45 credits or

activity hours of HIV and/or HCV-related

continuing education within the

preceding 36 months

Lipids

Clinical Lipid Specialist (CLS)

Accreditation Council

for Clinical Lipidology

https://www.lipidspecia

list.org/certchoose/cls/

• Completed a minimum of 10 continuing

education credit hours in clinical

lipidology in the previous 2 years

• Physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners,

physician assistants, pharmacists,

registered dieticians/nutritionists,

clinical exercise physiologists/specialists

ASHP Statement on the Role of Pharmacists in Primary Care 22

• 2000 hours of demonstrated clinical

experience in the management of

patients with lipid or other related

disorders

• Additional training requirements

Medication Therapy Management

Board Certified Medication

Therapy Management Specialist

(BCMTMS)

The National Board of

Medication Therapy

Management (NBMTM)

https://www.nbmtm.or

g/bcmtms/

• Pharmacy degree

• Pharmacy license

• 2 years of experience in MTM

experience or NBMTM training

Psychiatry

Board Certified Psychiatric

Pharmacist (BCPP)

Board of Pharmacy

Specialties

https://www.bpsweb.or

g/bps-

specialties/psychiatric-

pharmacy/

• Graduation from an ACPE accredited

pharmacy program

• Current license to practice

• Defined practice experiences or PGY2

Psychiatric Pharmacy Residency

*previously the Certified Diabetes Educator (CDE)

Copyright © 2022, American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. All rights reserved.